Human Trafficking

Excerpt from Judith G. Kelley, Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading State to Influence Their Reputation and Behavior, (Cambridge University Press, 2017): 65–75.

Photos via the UN.

The Problem of Human Trafficking

What Is Human Trafficking?

Human trafficking is the sale and exploitation of human beings. It differs from smuggling, which illegally moves people across borders at their request.1 Article 3, paragraph (a) of the 2000 Palermo Protocol (discussed more below) defines Trafficking in Persons as:

[T]he recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.

In some ways the problem is old, linked to traditional forms of slavery going back thousands of years to a time when such exploitation was normal and even legal. The terms “human trafficking” or “trafficking in persons” apply to the modern and more varied and hidden forms of severe exploitation of human beings.

The scope of the modern problem is difficult to assess but clearly large. The Palermo Protocol notes that trafficking can be for sexual exploitation or forced labor or organ removal. It is commonly understood to involve forced labor, bonded labor, child marriage, forced marriage, or the use of children in begging, warfare, prostitution, and much more. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) notes that of all the detected cases, nearly 40 percent are labor- related. Labor trafficking affects workers in sectors such as agriculture, domestic service, hospitality, construction, and garment and shoe production. Some trafficking, like Uzbekistan’s forcible cotton production, is government- sponsored. About half of all victims are thought to be women, one-fifth girls, and 12 percent boys, while about 72 percent of traffickers are male.2

Actual numbers of victims are unreliable.3 In 2002, the US State Department estimated there were between 700,000 to 4 million. A 2012 ILO estimate of forced labor came in at 20.9 million.4 By 2014, the US State Department noted that 44,000 actual victims had been identified in the past year, but that the real number of victims could be as high as 20 million. In 2014, a UNODC report covering the years 2010– 2012 reported having detected 510 actual trafficking flows of citizens from 152 different countries, but noted that these observed events are but the tip of the iceberg.5 It’s big business: A 2014 ILO Report estimated the illicit profits from forced labor and human trafficking at $150 billion.6

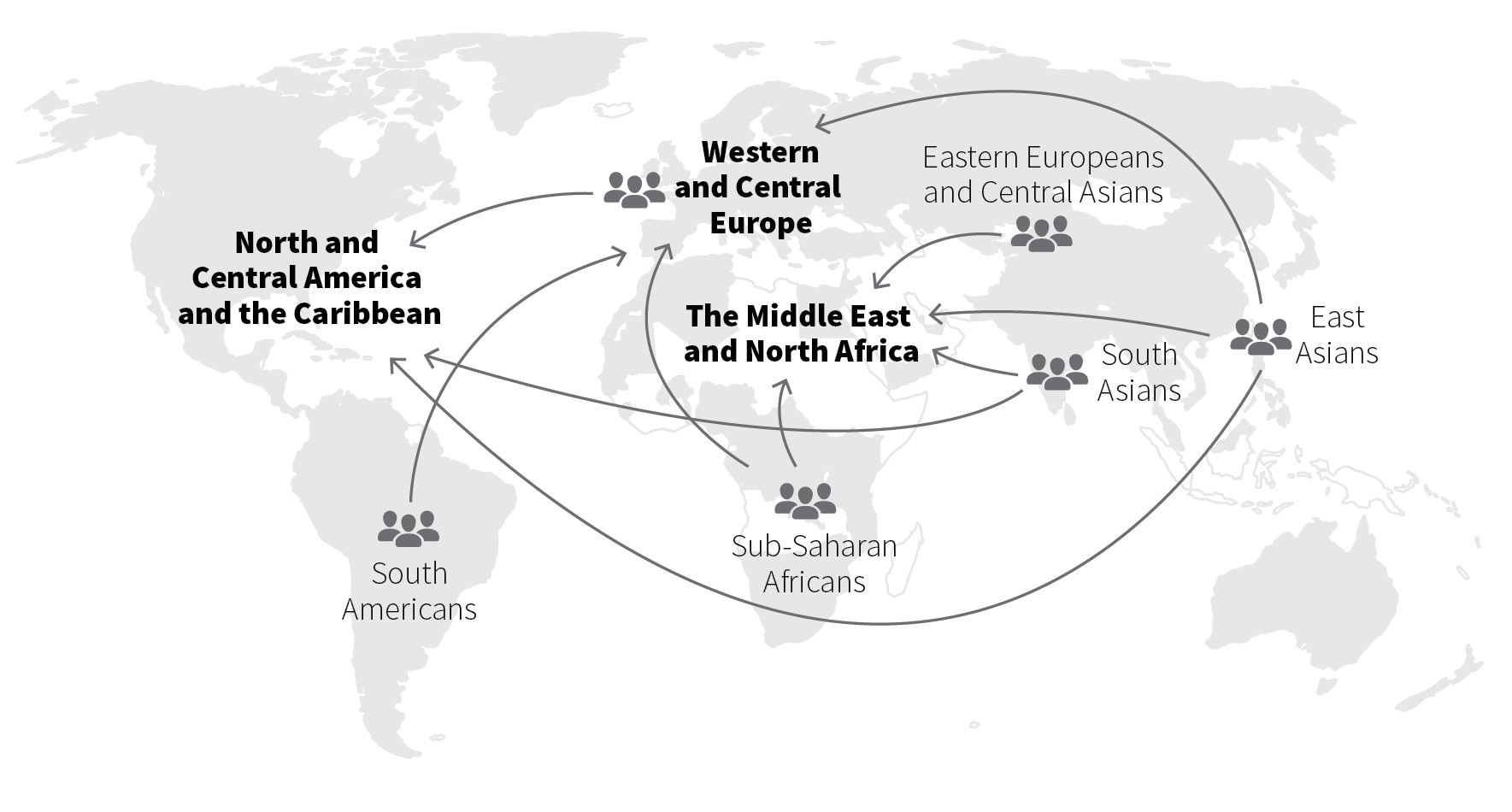

Figure 3.1. Human trafficking patterns of major origin and destination regions, 2010–2012.

The arrows show the flows that represent 5 percent or above of the total victims detected in the sub-regions.

Source: UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

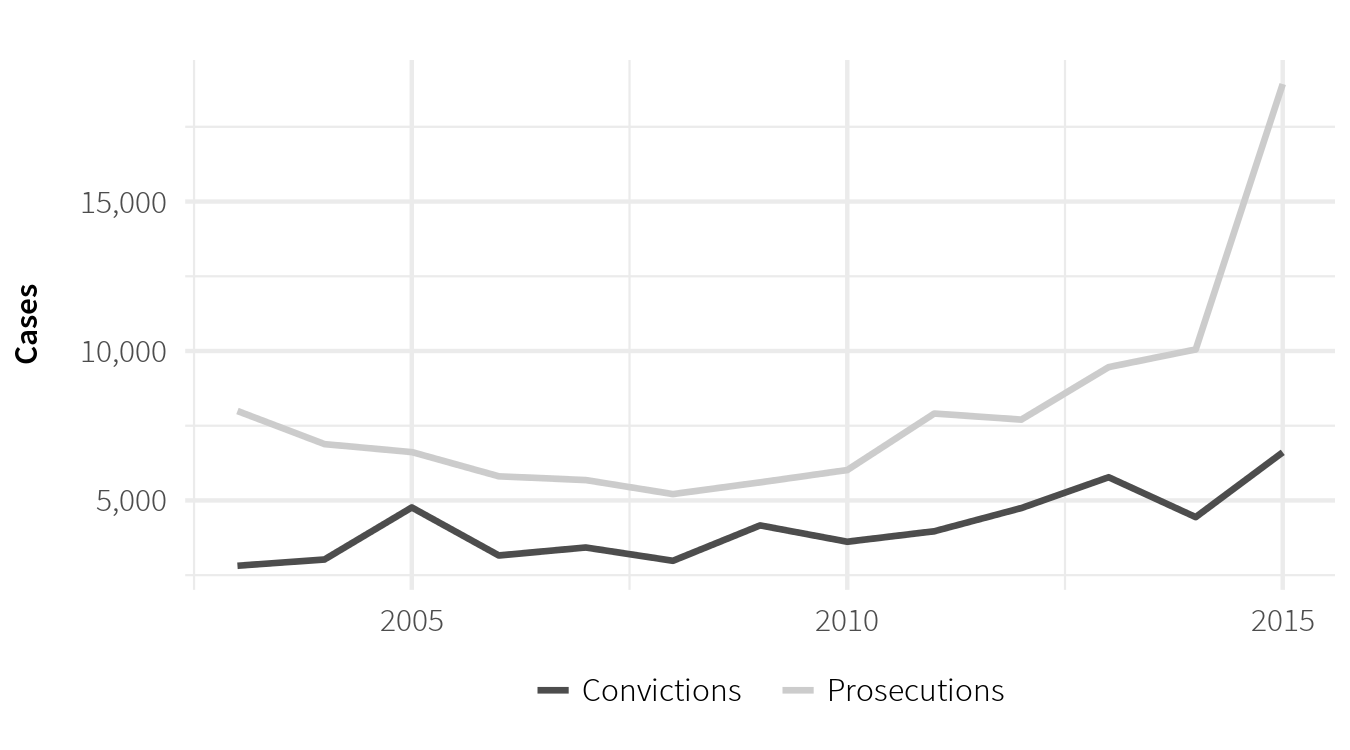

The pattern of movements varies across countries. Some countries are mostly sources of trafficking victims who are transported or travel to destination countries where they are victimized. Countries can also be transit countries, meaning that the victims travel or are transported through the country but neither originate nor remain there. Many countries can be classified as all three types. Given that trafficking can also take on many guises, countries face mixed challenges. Figure 3.1 displays the major movement patterns. Despite an increase in prosecutions and convictions, compared to the number of victims estimated above, human trafficking goes largely unpunished (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Human trafficking prosecutions and convictions worldwide, 2003–2014.

Source: 2007 and 2016 TIP Reports, section on “Global Law Enforcement Data.”

The Backdrop for Reputations: The Emergence of a Global Prohibition Norm

Scorecard diplomacy is a symbolic exercise that only works if it is grounded in a global normative or regulatory milieu such that violations or poor performance are widely considered undesirable. Global norms provide the mirror and the standards against which actors assess reputation.

In the area of human trafficking, such a global norm is now widely shared by multiple actors, including an array of intergovernmental organizations. However, for many years the world lacked an internationally accepted definition of trade and trafficking in human beings. Smuggling and illegal migration were lumped together with trafficking—a confusion still perpetuated by the media. Although trafficking has clear links to slavery, from the perspective of modern national criminal justice, human trafficking was a new crime lacking a proper legal framework. Over the last two decades, an international legal consensus has emerged on the nature of the “trafficking problem.”7 Even as implementation remains inadequate, states are increasingly accepting that it is their moral and legal responsibility to punish traffickers and protect victims. The emergence of this global consensus forms the essential background for anti- TIP scorecard diplomacy.

Anti-trafficking efforts date back to the anti-slavery movement, but the modern anti-trafficking regime is more recent.8 The precursors include various world conferences on women in the 1980s and 1990s, which framed women’s rights as human rights and focused attention on violence against women.9 The 1995 World Conference on Women in Beijing called for action against trafficking in women and children. For many years the issue of human trafficking had been framed around sexual exploitation, but in Beijing, forced labor and forced marriages were also included.10

Meanwhile rising concerns about transnational crime led the UN General Assembly to ask the Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice to analyze the incidence of various transnational organized criminal activities.11 The Assembly established an ad hoc committee to draft a multilateral protocol against transnational organized crime in 1998. Prompted largely by NGOs and faced with a rising incidence of human trafficking, poor domestic legislation and an inadequate international legal system, the issue of human trafficking was also making its way into the convention.

The topic of human trafficking also heated up in the US during the 1990s, propelled by an unusual coalition of feminists and religious conservatives. Efforts to fight the “moral scourge” of human trafficking found cross-party appeal and received broad support.12 After first being introduced by Representative Chris Smith (R-NJ) in 1998, on October 18, 2000 the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) became the backbone of the US anti-trafficking policy abroad.13 While the US domestic efforts to pass the TVPA gained momentum, the efforts to extend these efforts globally also got underway. The US quickly dominated the global policy arena and took a leading role in negotiations over the protocol and in the development of the norms embedded in the protocol.14 On Women’s Day, March 1998, US President Clinton referenced the “ 3Ps” that eventually made it into the protocol: to prevent trafficking, protect victims of trafficking, and prosecute traffickers.15 Later that year during the development of the proposed convention, the US introduced a resolution calling for a protocol on trafficking in women and children.16 After the resolution was adopted, the US and Argentina introduced the draft protocol.17 In November 2000 the Assembly adopted the Palermo Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons (Palermo Protocol) to the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and opened it to signature from December 12 to December 15.18 The protocol entered into force on September 29, 2003.

The drafters of the Palermo Protocol overcame many disagreements to reach the definition above. The NGO community was present in remarkable force and developed among themselves “a clear and savage rift.”19 The text was a compromise and some things were left unclear to accommodate differing views. In particular, “sexual” or “exploitation” was not defined clearly, reflecting a deep disagreement about whether prostitution can ever be voluntary. Some abolitionist groups in the US wanted the protocol to include voluntary prostitution. The coercion– consent debate necessitated some compromises that allowed both sides to claim victory.20 Ultimately the protocol made consent irrelevant in an effort to prevent offenders from using it as a defense,21 but it did not equate prostitution with trafficking.

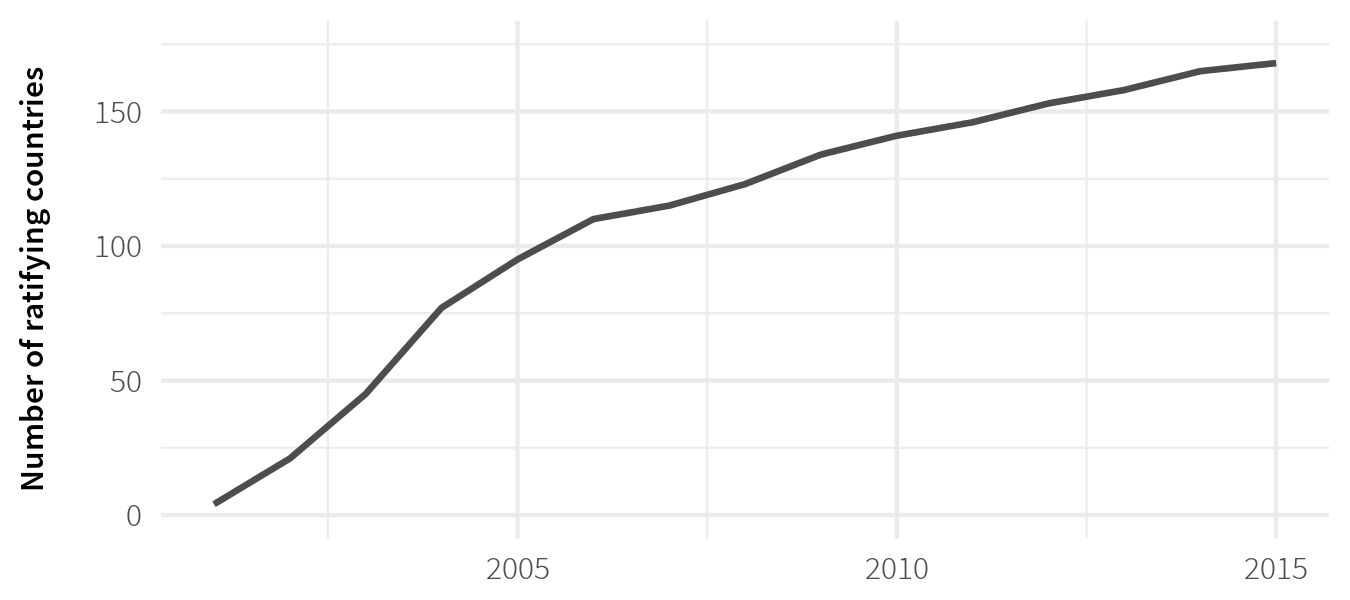

Since the passage of the protocol, the legal and political landscape around human trafficking has been “radically transformed,”22 and contributed to the global culture against human trafficking that forms the foundation of reputational concerns. Ratifications grew steadily after the protocol was created (see Figure 3.3). By 2015, 169 states were parties to the protocol, and several regional legal and policy instruments had emerged. In 2002 the UN developed the Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking and in 2005 the Council of Europe adopted the Convention on Action against Trafficking. These measures were supplemented by global efforts of several regional and international government organizations, as well as countries’ own expenditures on law enforcement, victim protection and assistance, awareness-raising programs, and so forth.23

Figure 3.3. Number of state parties to the Palermo Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons (Palermo Protocol) to the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime.

Source: UNODC.

IGOs focused on human trafficking include the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), which started the Global Programme against Trafficking in Human Beings in 1999, the International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Criminal Police Organization, and the International Organization for Migration. In 2007 UNODC launched UN.GIFT (United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking) with a large gathering in Vienna, Austria. In 2002 the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) adopted the Declaration on Trafficking in Human Beings that created so-called “national referring mechanisms” to facilitate coordination. The Council of Europe and the European Union have also been active, though the focus has largely been limited to member and neighbor states. The US has been at the forefront of leaning on governments around the world to live up to international standards.

The US definition of human trafficking used in the TIP Report has stimulated discussion about legal norms, the relationship between prostitution and trafficking,24 and the Western imposition of ideas. Some saw early US anti- TIP efforts as the president’s campaign to “promote restrictive policies on reproductive rights and sexuality throughout the world.”25 The issue of a person’s “consent” to transactional sex has loomed large in the US efforts to shape the Palermo Protocol and has, at times, created tensions that intersect with the US efforts on the ground. These debates are left outside the scope of this book, but are treated in depth elsewhere.26

Broadly speaking, however, a global prohibition against human trafficking clearly exists and has been growing over the last two decades. This has given the US a foil against which to reflect the performance of countries. The protocol provides standards that are widely accepted by major actors, lending moral force to efforts of US scorecard diplomacy to elicit reputational concerns by invoking these norms.

Doesn’t Everyone Want to Fight Human Trafficking?

One might argue that human trafficking stands apart in its ability to generate moral outrage. Certainly, it’s easier to generate opprobrium against human trafficking than against less morally abject issues such as banking regulations. Countries should therefore naturally want to address it, so little outside pressure should be necessary. Furthermore, one might argue that addressing human trafficking should not threaten domestic power holders in the way that curbing political repression or other human rights abuses might. This would suggest that there should be less resistance to curbing TIP than to increasing freedom of speech, for example.

However, other factors push against governments’ prioritizing this issue and lower the government’s sensitivity to problem, and, as discussed in Chapter 2, prioritization and sensitivity are crucial to success.

Few Direct Material Linkages

While countries might fear that a poor rating could affect trade, investment decisions, or tourism, and while such fear has been warranted in some cases such as Thailand,27 generally such fears are less common than for issues that bear directly on a state’s investment climate, such as its respect for intellectual property or its rule of law. TIP is mostly a soft issue that, as shown later, even the US has failed to tie to any real economic repercussions. Poor ratings do not predict less foreign direct investment (FDI), aid, or trade, for example, so countries may be less concerned about spillover effects on these. This decreases the instrumental salience discussed in Chapter 2.

Domestic Barriers to Addressing TIP

Addressing TIP poses several challenges, many of which lower its prioritization, and its normative and instrumental salience as discussed in Chapter 2.

First, human trafficking victims are often not constituents. Whether governments want to address a difficult domestic problem, such as illicit trade, depends on the domestic political economy of the issue. The illicit nature of trafficking rarely promotes a set of prominent and vocal actors. The victims are often from overseas or lack political empowerment, so, posing no threat at the ballot box, they are marginalized. Israel, for example, initially saw trafficked women as foreign prostitutes who could be ignored.28

Furthermore, cracking down on trafficking is costly and difficult. Addressing the problem may in itself attract attention to it, thus initially bring more costs than benefit for the government. Because it is driven by crime and poverty, it is also a difficult problem to address.29 It involves border issues, labor regulations, investigations and increased law enforcement, training, shelters, and inter-agency cooperation, which can create friction. This makes it hard for TIP to compete with other government priorities.

In addition, elites often benefit from trafficking. Where corruption thrives, the government may lack the will to combat illicit trade.30 Authoritarian governments often depend on loyalty among security forces and police, and if these forces benefit from trafficking in their districts—as is often the case—then cracking down on TIP can sow discontent and erode loyalty that is so often important for non-democratic power holders. Indeed, government complicity is rampant. Corrupt officials may take bribes for altering documents, or allowing border crossings. In 2014 police and government officials were sources of trafficking in 68 countries, topped only by organized criminal gangs.31 In Argentina, for example, the IOM Country Representative “identified official complicity at provincial and local levels and poor interagency coordination at all levels as impediments to effectively combating the problem.” He recounted a conversation he’d had with the interior minister who had told him that, “if the anti-TIP law applied to adult victims as well, the [government] would have to go after half of all provincial governors” and that this was why although “high-level officials may not be directly involved in trafficking activities, they are likely aware of the problem and are currently doing little to stop it.”32 Some governments outright exploit workers themselves, some of the most egregious examples of this being Uzbekistan’s cotton production program, Japan’s Industrial Trainee and Technical Internship Program, and the many forms of state-sponsored labor exploitation in Belarus.33

Another challenge is that, while international law bans human trafficking, different cultural or domestic traditions are more accepting. Different domestic norms lower the normative salience of the issue, as discussed in Chapter 2. Some Middle Eastern countries have long traditions of using domestic servants. They do not see it as a form of trafficking that workers have their passports taken away and are only allowed to be in the country if they work for one given employer, to whom are entirely beholden. Also in the Middle East, children used to be trafficked to serve as jockeys for camel racing, a practice widely condoned by inner circles of the regimes. Some countries view child marriage as culturally acceptable. In other countries such as Ghana, families send their children to work for the fishing industry, which is difficult to escape, or simply give children to extended family.34 In Chad, children are used for herding, and the cultural environment regards youth employment as normal.35 The president of the State Human Rights Commission has said that most TIP occurrences were instances of “indigenous citizens … participating in ‘cultural practices’ such as selling young daughters.”36 Cracking down on such traditions is challenging.

Conservative religious views may dismiss concern for victims. In some countries the views toward trafficking can be not only dismissive, but also outright condemning. In Iraq, for example, the US embassy reported:

Member of parliamentarian, [Nada] Ibrahim related that some officials could not overcome their personal and religious beliefs about trafficking to view TIP as a political issue. She recounted a conversation with Women’s Committee Chairwoman Sameera Al-Mousawi, who walked off the stage in the middle of a televised interview with Yanar Mohammed, an NGO activist, regarding female victims of sexual exploitation and trafficking. Ibrahim remembered that when she confronted Mousawi after the incident and asked her why she did not acknowledge the situation of female victims of trafficking as a political issue, Mousawi had responded by declaring that these women were “prostitutes who must die.” Ibrahim lamented that some [Iraqi] officials who might otherwise help Iraq make progress on TIP harbored strong personal beliefs that precluded their objective consideration of human trafficking as a political issue.37

Sometimes religious groups are outright complicit. For example, in Guinea- Bissau religious teachers lure boys by offering them education, but instead force them to beg in neighboring countries. In the 2014 TIP Report, religious groups are mentioned as sources of trafficking in 16 countries, so one cannot assume that the preferences of religious leaders align with the US in fighting trafficking.

Denial is often easier. While governments may not see human traffi cking as an immediate threat to their own power, denial is often easier than admitting to such an ugly problem. One IOM staffer noted how governments often refuse to acknowledge the problem: “The Bahamas really changed their song about this issue over time. First, they would say: ‘I don’t know what this country in that the report is about, but it’s not mine.’ Two years later they admitted they were wrong. Now we are working, talking about the TIP Report as well.”38 Such denial is common. In many countries, such as Algeria, US embassies have reported similar attitudes. Some governments consider human trafficking simply “an illegal immigration issue,” for example. Libya’s government lacked “even a rudimentary understanding of the phenomenon” and how to respond.39 In Tajikistan, the US embassy noted that government officials had “very little comprehension of our concerns about TIP … some prefer denial to engagement on difficult issues which require reform and self-criticism.”40 Such refusal to recognize the problem is a common obstacle to progress.

In sum, it’s probably easier to generate moral outrage about human trafficking than on many other issues. However, even if it is easier than, say, banking regulations or freedom of speech, this does not make it an easy case per se. It still requires political will, education, capacity, and resources. Just like murder and other heinous crimes, it is not about to be eradicated. Furthermore, even if governments care about their reputation on the issue, many lack the capacity and know-how to deal with the issue.41

As the previous chapter noted, the way a country views an issue and the extent to which it prioritizes it will modify its concern. Chapter 7 will examine how some of these factors discussed above modify the influence of scorecard diplomacy. For now, having discussed the global regime against human trafficking and the nature of human trafficking as a policy problem and subject for influence by international actors, this chapter turns to explain how the US has implemented the first two steps of the scorecard diplomacy cycle.

References

Ad Hoc Committee on the Elaboration of a Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. 1999. Revised Draft Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. New York: United Nations General Assembly.

Bertone, Andrea Marie. 2008. “Human trafficking on the international and domestic agendas: Examining the role of transnational advocacy networks between Thailand and United States.” Dissertation. Edited by College Park University of Maryland.

Butcher, Kate. 2003. “Confusion between prostitution and sex trafficking.” The Lancet 361 (9373): 1983.

Chuang, Janie. 2005. “The United States as global sheriff: Using unilateral sanctions to combat human trafficking.” Michigan Journal of International Law 27: 437–437.

———. 2012. “The use of indicators to measure government responses to human trafficking.” In Governance by Indicators: Global Power through Classification and Rankings, edited by Kevin Davis, Angelina Fisher, Benedict Kingsbury, and Sally Engle Merry, 317–344. Oxford University Press.

———. 2013. “Exploitation creep and the unmaking of human trafficking law.” Unpublished paper, American University, Washington, DC.

———. 2015. “Exploitation creep and the unmaking of human trafficking law.” The American Journal of International Law 108 (4): 609–649.

Clinton, William J. 1998. Memorandum for the Secretary of State, the Attorney General, the Administrator of the Agency for International Development, the Director of the United States Information Agency, Subject: Steps to Combat Violence Against Women and Trafficking in Women and Girls.

DeStefano, Anthony. 2007. The War on Human Trafficking: US Policy Assessed. Rutgers University Press.

Doezema, Jo. 2002. “Who gets to choose? Coercion, consent, and the UN Trafficking Protocol.” Gender & Development 10 (1): 20–27.

Efrat, Asif. 2012. Governing Guns, Preventing Plunder: International Cooperation against Illicit Trade. Oxford University Press.

Foester, Amy. 2009. “Contested bodies.” International Feminist Journal of Politics & Society 11 (2): 151–173.

Fredette, Kalen. 2009. “Revisiting the UN Protocol on Human Trafficking: Striking balances for more effective legislation.” Cardozo J. Int’l & Comp. L. 17: 101.

Gallagher, Anne, and Paul Holmes. 2008. “Developing an effective criminal justice response to human trafficking lessons from the front line.” International Criminal Justice Review 18 (3): 318–343.

Gallagher, Anne. 2001. “Human rights and the new UN protocols on trafficking and migrant smuggling: A preliminary analysis.” Human Rights Quarterly 23 (4): 975–1004.

———. 2014a. “The global slavery index is based on awed data: Why does no one say so?” Guardian, November 28, 2014. Accessed December 21, 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2014/nov/28/global-slavery-index-walk-free-human-trafficking-anne-gallagher.

Hyland, Kelly E. 2001. “The impact of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children.” Human Rights Brief 8 (2): 12.

International Labour Organization. 2012. ILO Global Estimate of Forced Labour 2012: Results and Methodology. Geneva.

———. 2014. Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labour. Geneva.

Kessler, Glenn. 2015. “Why you should be wary of statistics on ‘modern slavery’ and ‘trafficking’.” Washington Post, April 24, 2015. Accessed December 17, 2015. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/fact-checker/wp/2015/04/24/why-you-should-be-wary-of-statistics-on-modern-slavery-and-trafficking/.

Lerum, Kari, Kiesha McCurtis, Penelope Saunders, and Stéphanie Wahab. 2012. “Using human rights to hold the US accountable for its anti-sex trafficking agenda: The universal periodic review and new directions for US policy.” Anti-Trafficking Review 1: 80–103.

Masenior, Nicole Franck, and Chris Beyrer. 2007. “The US anti-prostitution pledge: First Amendment challenges and public health priorities.” PLoS Medicine 4 (7): e207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040207.

Mertus, Julie, and Andrea Bertone. 2007. “Combating trafficking: International efforts and their ramifications.” In Human Trafficking, Human Security, and the Balkans, edited by Richard Friman and Simon Reich, 40–16. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Oldfield, John R. 1998. Popular Politics and British Anti-Slavery: The Mobilisation of Public Opinion Against the Slave Trade, 1787–1807. Vol. 6. Psychology Press.

Ollus, Natalia. 2008. The United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children: A Tool for Criminal Justice Personnel. Resource Material Series No. 62, 16–30. Accessed December 21, 2016. http://www.unafei.or.jp/english/pdf/RS_No62/No62_07VE_Ollus2.pdf.

Protection Project. 2014. The Protection Project Review of the Trafficking in Persons Report.

Richards, Kathy. 2004. “The trafficking of migrant workers: What are the links between labour trafficking and corruption?” International Migration 42 (5): 147–168.

Sychov, Alyaksandr. 2009. “Human trafficking: A call for global action.” Global Strategy Journal 22 (14): 1–11.

United Nations. 2000. United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime (with protocols). New York.

UNODC. 2014. Global Report on Trafficking in Persons.

US Congress. 2014. Effective Accountability: Tier Rankings in the Fight Against Human Trafficking. Hearing before the Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations, April 29, 2014. Edited by the Committee on Foreign Affairs.

US Department of State. 2015. Annual Report on Trafficking in Persons.

Weitzer, Ronald. 2005. “The growing moral panic over prostitution and sex trafficking.” The Criminologist 30 (5): 1–5.

Wyler, Liana, Alison Siskin, and Clare Ribando. 2009. Trafficking in Persons: U.S. Policy and Issues for Congress. Congressional Research Service.

Wyler, Liana. 2013. Trafficking in Persons: International Dimensions and Foreign Policy Issues for Congress. Congressional Research Service.

International Labour Organization 2012.↩

UNODC 2014.↩

Kessler 2015. The number in the Global Slavery Index are deeply flawed. Gallagher 2014a.↩

International Labour Organization 2012.↩

UNODC 2014.↩

International Labour Organization 2014.↩

Gallagher and Holmes 2008, 318– 319.↩

Oldfield 1998.↩

This section draws on Bertone 2008, 21ff.↩

A thorough treatment of the rise of anti-trafficking policy both internationally and in the US including various ideological debates can be found in Bertone 2008 and in Efrat 2012.↩

United Nations 2000, 610.↩

Miller and Horowitz interviews. Also DeStefano 2007.↩

Others have described the history and spirit of this act. See for example Efrat 2012, Ch. 5, DeStefano 2007.↩

Chuang 2015, 610, Bertone 2008, 24.↩

Clinton 1998.↩

Hyland 2001, 1. Argentina had already suggested drafting a convention against trafficking in minors and Greece had followed up by suggesting this be broadened to all trafficking. Ollus 2008, 16, 20.↩

Ad Hoc Committee on the Elaboration of a Convention against Transnational Organized Crime 1999. See the procedural history at the Convention website United Nations 2000.↩

Hyland 2001, Fredette 2009. Hyland attributes the new protocol to five factors: NGO lobbying of governments on behalf of trafficking victims, an increase in victims with more data becoming available to document the trend, a turn to view trafficking as a crime issue with increasing negative externalities, the difficulties of prosecuting trafficking offenders in the absence of national laws, and the inadequacy of international legislation to address the modern aspects of the problem, including the recognition of a broader range of victims and acts that qualified as trafficking.↩

Gallagher 2001, 1002.↩

Doezema 2002.↩

Gallagher 2001, 985.↩

Gallagher and Holmes 2008, 318.↩

Sychov 2009.↩

Lerum et al. 2012. The creators behind the TVPA wanted to eliminate prostitution and sought bans on funding to anything related to prostitution or to organizations that did not renounce prostitution. This became part of the Bush administration’s global anti-prostitution policies, which prohibited anti-TIP funding to some organizations. These policies were eventually eliminated in a 2013 Supreme Court ruling.↩

Foester 2009, 153.↩

Butcher 2003, Weitzer 2005, Masenior and Beyrer 2007. A critical discussion of the way the US has defined trafficking norms compared with the UN protocol can be found in much of the work of Chuang and is also discussed in various Congressional research reports. Wyler et al. 2009, Wyler 2013, Chuang 2015, 2013, 2012, 2005.↩

For more on Thailand, see Chapter 5.↩

Efrat 2012, Richards 2004.↩

Mertus and Bertone 2007.↩

Efrat 2012, 278.↩

Protection Project 2014, 41.↩

07BUENOSAIRES1353.↩

US Congress 2014. See also the 2015 US TIP Report narrative on Belarus. US Department of State 2015.↩

Mahamoud interview.↩

09NDJAMENA230.↩

09MEXICO3173.↩

10BAGHDAD480.↩

Interview #3.↩

06TRIPOLI671.↩

09DUSHANBE1319.↩

Efrat 2012, 222.↩