Zimbabwe

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/zimbabwe/.

PDFContents

The US had very limited success in producing anti-TIP progress in Zimbabwe. The US’s poor relationship with the Zimbabwean government, combined with the GOZ’s lack of concern for human rights abuses and the many sanctions it already faced, meant the GOZ gave almost no concern to its Tier rating. The US embassy, faced with what it considered more important political priorities in Zimbabwe, resisted placing too much pressure on the TIP issue and feeding anti-US propaganda.

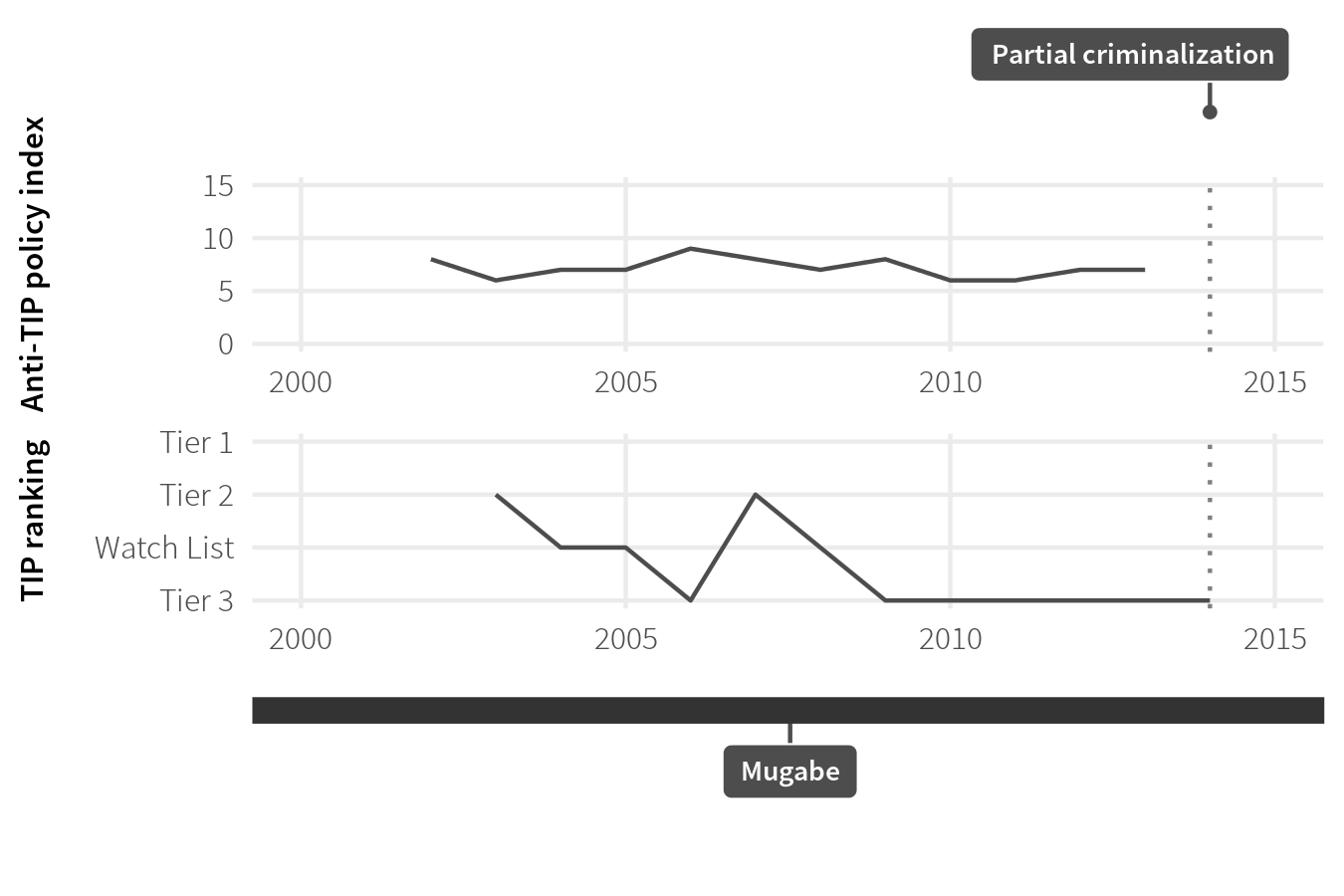

Figure 15: Zimbabwe’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2000–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $820.12 |

| Total aid | $6,737.73 million |

| Aid from US | $1,681.96 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 5.13% |

| Total TIP grants | $670,000 |

Table 15: Key Zimbabwean statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Outcomes

The US embassy has had a “severely strained”1 relationship with Zimbabwe’s government, which has maintained power though violence and intimidation. Before the Unity Government of 2009, there was little direct communication on TIP; even Zimbabwe’s first downgrade to the watch list in 2004 solicited little reaction. The government did not provide any information for the interim assessment, and embassy staff could not secure meetings with officials, whom the embassy said were “suspicious of foreign inquiries and afraid of disclosing information that might be prejudicial to the GOZ if publicized.”2 The embassy feared that too much pressure on TIP would interfere with other US priorities in Zimbabwe and that information on TIP was too anecdotal to make credible judgments.3 After the 2006 downgrade to Tier 3, attention refocused somewhat in the wake of general international hostility from the international community over Zimbabwe’s Operation Restore Hope, which bulldozed slums and displaced hundreds of thousands of people.

Legislation

After the Unity government in 2009, the government became more responsive to a variety of actors, including the US, pressuring it on TIP legislation. 4 The US embassy began to supply draft laws and helped a top official prepare briefings for the prime minister. However, other actors remained important. The IOM likewise had a consultant working with the government on the TIP law,5 and South Africa also pushed for criminalization of TIP. The draft legislation was supposedly finalized and introduced to the Council of Ministers for debate in September 2010. While there were efforts in 2011-2012 to move the bill along, the Ministry of Justice publicly denied the existence of a trafficking problem and the issue lingered despite the repeated Tier 3 designations. The government didn’t issue temporary regulations until January 2014,6 and Parliament passed these only in March 2014.7 The act also established a committee to draw up an action plan.8 Thus, in Zimbabwe, progress has been slow. For a long time the low ratings appeared to have little effect, and the US has mostly supported other actors to lead the efforts.

Institution building and the promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

There is no evidence that the US efforts contributed to institution building or socialization around TIP issues. Any institutional steps, such as the inter- ministerial task force, fell short due to lack of resources. NGOs and IGOs provide almost all the services.9 The government has persisted in denying the existence of any significant problem.

Indirect pressure

Rather than the US embassy, the primary actor has been the IOM,10 supplemented by UNICEF and also many local and international NGOs. Illustrating the model of scorecard diplomacy, however, IOM efforts have often been supported by US funding.11 Together these actors have provided the bulk of victim services, training, and awareness campaigns. Recognizing this, the US embassy has sought to operate in the background by cooperating with and funding the NGOs and IGOs and helping to organize meetings between stakeholders.12

Concerns

The government showed little reaction to the bad Tier ratings. When the 2006 TIP Report demoted Zimbabwe to Tier 3, it technically became subject to sanctions, but given that so many other sanctions already were in effect against Zimbabwe, the impact was minimal. Zimbabwe quickly rejected the report,13 dismissing it as a ploy by the Americans to vilify Zimbabwe.”14

Regional pressure might have been more important. When South Africa hosted the 2010 World Cup, it tried to encourage Zimbabwe to pass anti-trafficking legislation in advance of the Cup. The Attorney General was surprised that “even Mozambique” had introduced anti-trafficking legislation, and from that point began to promote its passage in Zimbabwe.15

Conditioning factors

Scorecard diplomacy in Zimbabwe was hindered by the poor relationship with the government and the embassy’s need to balance many competing priorities in Zimbabwe. The US fear that the TIP criticisms would interfere with other agenda items was demonstrated by the ambassador’s reaction to the news in 2004 that the State Department intended to drop Zimbabwe to Tier 3. In a cable entitled “TIP and our Agenda in Zimbabwe,” the ambassador registered his “serious concern over Zimbabwe’s proposed inclusion on Tier 3.” While acknowledging that “the GOZ’s comprehensive maladministration has precipitated ongoing political and economic crises,” he objected on two grounds: First, the embassy wasn’t really sure there was a big TIP problem, and second, he worried about that a Tier 3 designation would undermine US efforts to address Zimbabwe’s other substantial problems. More important, he argued, was the ongoing rule the US was playing in shaping “in shaping the intellectual debate inside Zimbabwe [on democracy] and, increasingly significantly, throughout the region over pivotal issues in Zimbabwe’s crisis.” He worried that poorly documented accusations about TIP would undermine the embassy’s credibility:

The department has countered shrill GOZ propaganda and disinformation with strident criticism on specific, documented problems. The judiciousness of our attacks and our disassociation from sensationalized, unsubstantiated allegations against the [government] are critical to our credibility with local audiences and with key regional players whose greater involvement we are encouraging. A Tier 3 sanction resting on anecdotal evidence and innuendo would play into the hands of GOZ propagandists and deal a setback to our credibility with domestic and regional audiences.16

He was apparently persuasive enough, as Zimbabwe instead ended up on the watch list rather than Tier 3. Still, this pattern of optimism about Zimbabwe’s efforts on the part of the US embassy and criticism from the State Department continued, illustrating their different priorities on the matter.17

In addition to these diplomatic troubles and relatively low priority of the TIP issue for the embassy in the midst of political and economic crises, poor capacity and resources, poor TIP data, rampant corruption and official complicity in trafficking hampered scorecard diplomacy.18 Importantly, amidst the many direct human rights violations in the country, Zimbabwe’s government displayed low concern for its reputation on TIP.

The only hope for the US efforts was the good working relationships with NGOs and the IOM, through whom the US had to channel its resources and efforts to assert any influence on trafficking.

08HARARE903↩

04HARARE1878↩

04HARARE691↩

09HARARE650↩

09HARARE678↩

ZimSitRep_J, “Bill Watch 1/2014 of 8th January [Anti-Trafficking in Persons Regulations Gazetted],” Zimbabwe Situation, 9 Jan. 2014, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/zimsit_bill-watch-12014-8th-january-anti-trafficking-persons-regulations-gazetted/.↩

Mbiba, Lloyd, “Zim Passes New Human Trafficking Bill,” dailynews, 10 March 2014, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.dailynews.co.zw/articles/2014/03/10/zim-passes-new-human-trafficking-bill.↩

ZimSitRep_M, “President Establishes Anti-Trafficking Committee,” Zimbabwe Situation, 14 Jan. 2015, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/zimsit_w_president-establishes-anti-trafficking-committee-the-herald/.↩

09HARARE177↩

09HARARE177↩

06HARARE374↩

06HARARE1490↩

“VOA NEWS: HARARE REJECTS U.S. HUMAN TRAFFICKING ALLEGATIONS.” US Fed News. June 7, 2006 Wednesday 2:25 AM EST . LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2012/07/27.↩

“Zimbabwe; Govt Denies Human Trafficking Reports.” Africa News. (November 23, 2006 Thursday): 595 words. LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2012/07/27.↩

09HARARE678↩

04HARARE691↩

05HARARE339↩

08HARARE1030↩