Oman

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/oman/.

PDFContents

Because Oman was so concerned with its image, the US was successful in bringing attention to trafficking and bringing about legal changes. Meetings occurred at high levels and were at times frequent. The country’s first inclusion in the TIP Report was in 2005, when Oman was rated Tier 2. The 2006 report dropped Oman to the Watch List, and when the US saw no improvement, in 2007 and 2008 Oman was rated the lowest Tier 3. The low ranking prompted a severe crisis in the relationship and resulted in cancelled meetings and combative ultimatums. Eventually, this confrontation did lead to new legislation being passed and to practices in some areas of trafficking improving. The US embassy engaged strongly with Omani officials on the topic, discussing TIP in meetings at least 6-8 times a year and often bringing the issue up directly in meetings one on one with the ambassador and high-level officials such as the labor minister.

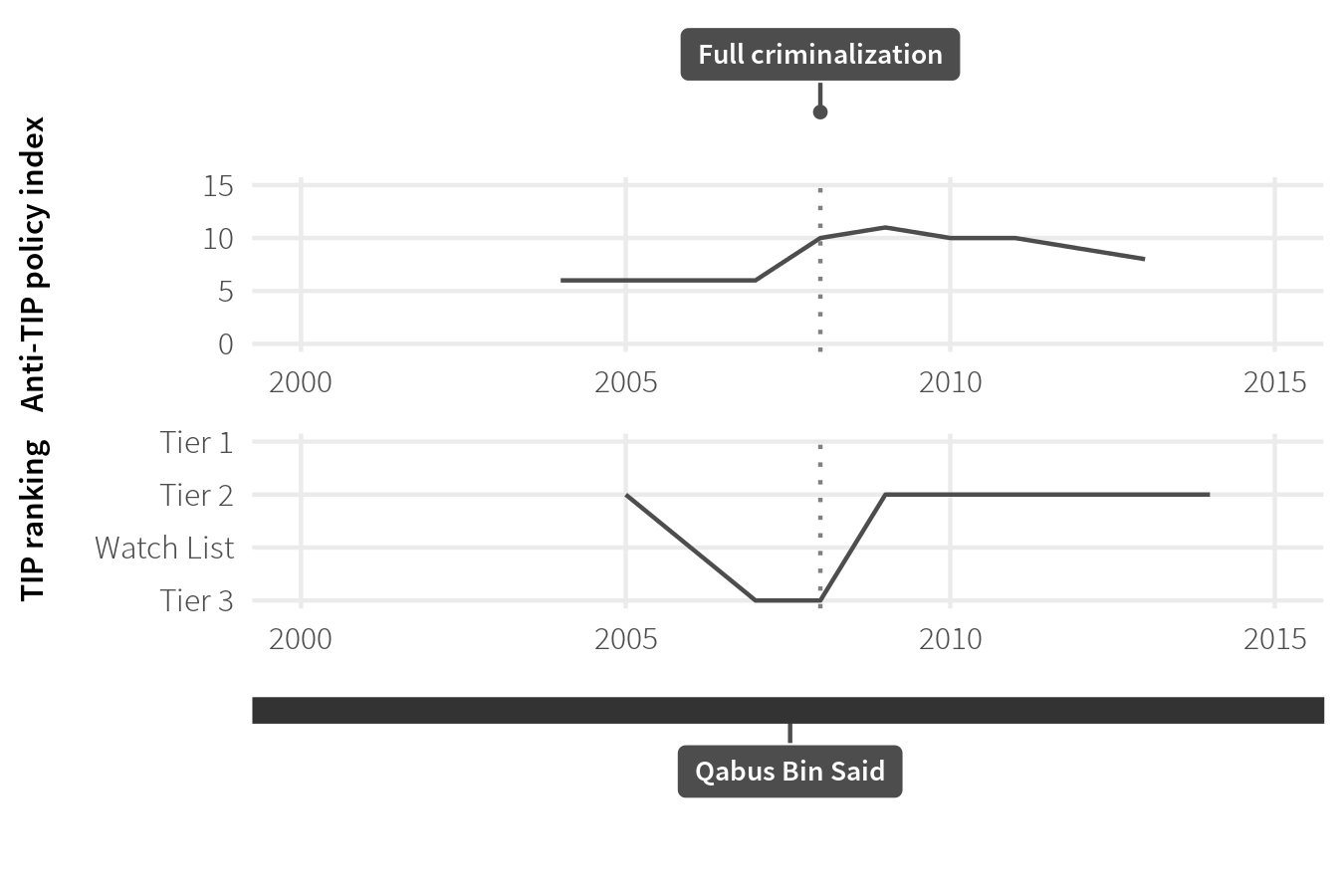

While the US exerted considerable influence and progress was made in the late 2000s, it has since stalled. Figure 13 shows how the severe drop in the tier rating correlated with improvements in policies, but also how the lack of tier pressure since then has been matched by increasing complacency in the government efforts.

The Oman case thus illustrates just how serious some countries take the tier ratings and the high level of politics they can reach, but also that the concern may be more with appearances than substance. Such concern can be elicited to prompt change, but this may remain superficial.

Background

Although its labor practices and laws presented conditions that were very conducive to labor exploitation, especially of foreigners, Oman was ignoring human trafficking in the early 2000s. With over 640,000 undocumented foreign workers, making up 80-85 percent of the private workforce, abuses were prevalent, especially given the practice of withholding passports from domestic workers.1 As in some other Arab countries, there were reports of issues with children trafficked for use as camel jockeys,2 and with about a quarter to half of Oman’s labor force being foreign, Oman’s “sponsorship system” of migrant workers left many in the complete control of employers.

Figure 13: Oman’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2000–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $18,421.38 |

| Total aid | $2,721.23 million |

| Aid from US | $44.86 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 0.574% |

| Total TIP grants | $70,000 |

Table 13: Key Omani statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Indirect pressure

Indirect pressure was not a significant factor in enhancing scorecard diplomacy in Oman. The media, being mostly under state influence, was generally not helpful to the US efforts. Rather, the government used the media to defend its image and criticize the reports in public.3 The US also was unable to work much through NGOs, which were quite scarce in Oman.

IGOs were a bit more active. The UN sent a Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons on a five-day fact-finding mission, and the subsequent report made it clear that the UN shared the US concerns, which made it harder for Oman to simply frame US criticism as political blackmail. Nevertheless, the UN did not have much direct involvement thereafter. 4 The ILO has also been active in Oman, but extensive cooperation with the US is not evident.5

Concerns

Oman was highly concerned with losing face and was worried about its domestic and international image. As one embassy cable pointed out after the 2007 drop to Tier 3, “It is exceptionally rare for Omanis to hear information critical of their country. So, the Tier 3 ranking came as a major embarrassment for Oman, and top officials are feigning surprise.” 6 While keen to take actions to improve its rating, officials were also concerned with not wanting to be seen to cower to US demands.7 The state-owned daily Observer and private daily Times of Oman ran articles interviewing South Asian and Western expats, who added their voices of support to Oman’s rejection of the TIP Report. In the fall of 2007, a US cable noted, “The discrepancy between shock and anger expressed in public and the government’s steady, yet quiet action suggests that the government may be trying to save face while attempting to fulfill the recommendations in the TIP action plan.”8 After the 2008 Tier 3 rating, it was so upset that it even enlisted the Gulf Cooperation Council to endorse the Sultan’s official rejection of the US report.9 After the extensive domestic reaction, the embassy described Oman as “[f]eeling that its Sultan has been dishonored and its national honor has been impugned…” 10 To protect its image, the government promoted massive criticism of the US report in the media and the Omani Journalists Association condemned the report as false allegations. 11 An official told the embassy that, “although the Sultan was very upset about the report, Qaboos was more concerned about the international image of his country.” 12 The CEO of the Oman Petroleum Services Association (OPAL), who also advised the Minister of Manpower on labor affairs, told the embassy “that it was unfortunate that the USG published its report while the Sultan is outside of Oman on his European trip and therefore more exposed to international scrutiny and criticism. ‘You likely caught him by surprise,’ Balushi surmised, forcing the Sultan to defend his country before Western leaders and explain why Oman is not like the other countries on Tier 3.”13 Thus, both in 2007 and 2008, the reactions were all very much about image.

The concern with loss of face was also partly because Oman feared the practical repercussion of a reputational loss. The chairman of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry (OCCI) told the embassy he was concerned that the Tier 3 ranking would hurt Oman’s trade and investment.14 Sanctions fears, however, were not a big issue. In all the cables, an actual Omani reaction to the sanction threat was only mentioned once, and in that context, the MFA reaction was one of “disbelief and confusion” over possible sanctions, and the US embassy immediately recommended a waiver.15 It was probably clear to all that sanctions were not going to happen. Indeed, Oman seemed to be the one with the leverage. As the embassy noted, in addition to aid, “Post’s Office of Military Cooperation (OMC) currently is managing 52 active Foreign Military Sales (FMS) cases valued at $1.04 billion …[]… The sequencing of the TIP Report’s release and the start of [Gulf Security Dialogue] consultations in Washington may cause some problems with the latter. We therefore recommend that the Department arrange a meeting between under secretaries Badr and Dobriansky to clarify the USG position on TIP in the larger context of regional and national security.” 16 Concerns about image thus were partly about how it might harm trade and investment.

Given its strong concern, Oman acted sought to raise its rating to improve its image.17 That its concern with trafficking was not intrinsically motivated to improve trafficking but rather to improve the rating was clear by its attempts to threaten the US to change its rating,18 which by and large succeeded and led to celebration in the state-directed news media, showing the concern with maintaining a good domestic reputation.19

Outcomes

Legislation

Many of Oman’s actions on TIP can be traced to specific US recommendations, and its been documented that in 2007 after the drop to the tier 3 rating, Omani officials took notes in meetings with US officials about what they needed to do.20 The US was heavily involved with the drafting of TIP legislation.21 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs requested and received examples of anti-TIP legislation from the US embassy,22 and the embassy reported that “comments provided by an expert contracted by G/TIP have been well-received by Oman’s anti-trafficking committee.” 23 Omani officials themselves recognized the external assistance on the legislation.24

Because passage of the law was still pending, however, in the summer of 2008 the US kept Oman at Tier 3. Omani officials were furious. In a June 11, 2008 cable to Washington ominously titled “Addressing our Tier 3 TIP dispute with Oman,” the embassy reported that it had told Oman that the rating couldn’t be changed without some action from Oman, and lamented, “We therefore are caught in a dispute in which there is little common ground, and with a partner that has indicated its willingness to wager the relationship on the outcome of the matter.” The cable goes on to consider the various issues at stake, including the FTA and Omani support of the middle East Peace Process.25 After the 2008 rating was released, the media fed public outrage in Oman and regional states, leading the embassy to note: “It appears that Oman is willing to stoke this popular resentment in its drive to get the Tier 3 ranking retracted.” 26 The US eventually caved in and “revised”27 the rating, based on a promise from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Secretary General on the anti- trafficking legislation still in process: “Our friends did not let us down, and we will not let them down.”28 He stated that he had seen the final version of Oman’s new anti-TIP law, currently with the Council of Ministers for review, and that news of the President’s determination would allow the legislation to move to the “fast track” for approval.” The promise was kept. After the November 2008 passage of the new law criminalizing human trafficking, the embassy noted, “The new law as adopted is almost the same as an earlier draft that won approval from the USG-funded international expert that worked with Oman on the legislation.” 29 The link between US recommendations and the new law is thus very strong both in timing and content.

Other efforts to follow US recommendations include the distribution of pamphlets, public awareness campaigns, a directive on passports, and construction of a shelter.

After the 2008 confrontation,30 Oman settled, perhaps too comfortably, at Tier 2. The TIP Report continues to acknowledge that the government is trying, but lament the “modest effort,” “minimal progress”, or even “no discernible” efforts across some areas of performance.

Institution building

Aside from building a shelter, there is no evidence in the cables that the US influenced domestic institutions in Oman.

Promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

The US has helped change the norms around camel racing and the issue of human trafficking have become acknowledged as a problem. Otherwise, however, it has not changed attitudes: concern with trafficking was clearly not intrinsically motivated. Efforts were geared purely at improving the rating itself, not the underlying conditions. This was clear by its attempts to threaten the US to change its rating.

Conditioning factors

Major obstacles to US scorecard diplomacy include the government’s complete denial of the problem and its full control of the domestic media. The fact that the government clearly was willing to let the issue spill over into other areas of cooperation and threaten the US contributed to a highly confrontational relationship. Nonetheless, some progress was achieved because of the government’s strong professed concern about its domestic and international image, as well as its concern about spillovers into trade.

08MUSCAT184↩

05ABUDHABI4979↩

07MUSCAT822↩

06MUSCAT1575↩

http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/news/WCMS\_146443/lang--en/index.htm↩

07MUSCAT822↩

07MUSCAT822↩

07MUSCAT822↩

Accessed December 27, 2016.

08MUSCAT469↩

08MUSCAT431↩

Oman Tribune, Sultanate hails US on trafficking list move. Available at http://www.omantribune.com/index.php?page=news&id=37393&heading=Other%20Top%20Stories Last accessed 19 Oct. 2015.↩

08MUSCAT634↩

08MUSCAT464↩

07MUSCAT788↩

07MUSCAT597↩

08MUSCAT425, 07MUSCAT597↩

08MUSCAT634↩

08MUSCAT431↩

Oman Tribune, Sultanate hails US on trafficking list move. Available at http://www.omantribune.com/index.php?page=news&id=37393&heading=Other%20Top%20Stories Last accessed 19 Oct. 2015.↩

08MUSCAT409↩

07MUSCAT193, 07MUSCAT778↩

07MUSCAT193↩

07MUSCAT734↩

07MUSCAT778↩

08MUSCAT431↩

08MUSCAT443↩

The US president issued a waiver. The move was essentially to upgrade Oman to the watch list. However, the Tier was not retroactively revised. Officially, the presidential determination was to “Make the determination provided in section 110(d)(3) of the Act, concerning the determination of the Secretary of State with respect to Moldova and Oman.” The White House, “Presidential Determination No. 2009–5 of October 17, 2008. Presidential Determination With Respect To Foreign Governments’ Efforts Regarding Trafficking In Persons.” Section 110(d)(3) is regarding “Subsequent compliance.”↩

08MUSCAT732↩

08MUSCAT830↩

08MUSCAT425, 08MUSCAT431, 08MUSCAT527, 07MUSCAT597_a↩