Nigeria

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/nigeria/.

PDFContents

In Nigeria, pressure from the scorecard diplomacy has motivated the government to improve its reputation on TIP. Nigeria was included in the very first 2001 TIP Report as a Tier 2 country. At that time there appeared to be hesitation by some government officials to discuss trafficking, and an August 2, 2001 diplomatic cable describes a Foreign Ministry official as “visibly uncomfortable when asked about ongoing trafficking in persons.”1 The US attention towards the issue contributed towards the establishment of institutions like the National Task Force on Trafficking, which led to the passage of comprehensive legislation that created a highly successful federal agency dedicated to fighting trafficking, the National Agency for the Prohibition of Traffic in Persons (NAPTIP). Rather than leading to a lull in activity, Nigeria’s excitement about achieving Tier 1 ranking in 2009 spurred more anti-trafficking work. Although the ranking has since been adjusted to the more realistic Tier 2, Nigeria continues to focus attention on trafficking. It’s performance on human trafficking far outshines that on other human rights conditions in the country, meanwhile raising concerns that countries may excel in one area that is a strong focus on scorecard diplomacy, while neglecting other areas.

Overall, however, Nigeria provides an example of how US scorecard diplomacy can motivate government officials to focus attention on the problem, and, when political will exists, lead to successful changes in legislation, implementation, and institutions.

Background

The trafficking problem in Nigeria is large and diverse in nature. Early TIP reports noted that most trafficking from Nigeria was of women going to Europe and cited an Italian authorities’ estimate of 10,000 Nigerian prostitutes working in Italy. Women and children are also trafficked to on plantations in other African countries and are subjected to sex trade and forced begging in Nigeria and abroad. The rising prominence of the terrorist organization Boko Haram has exacerbated abuses.

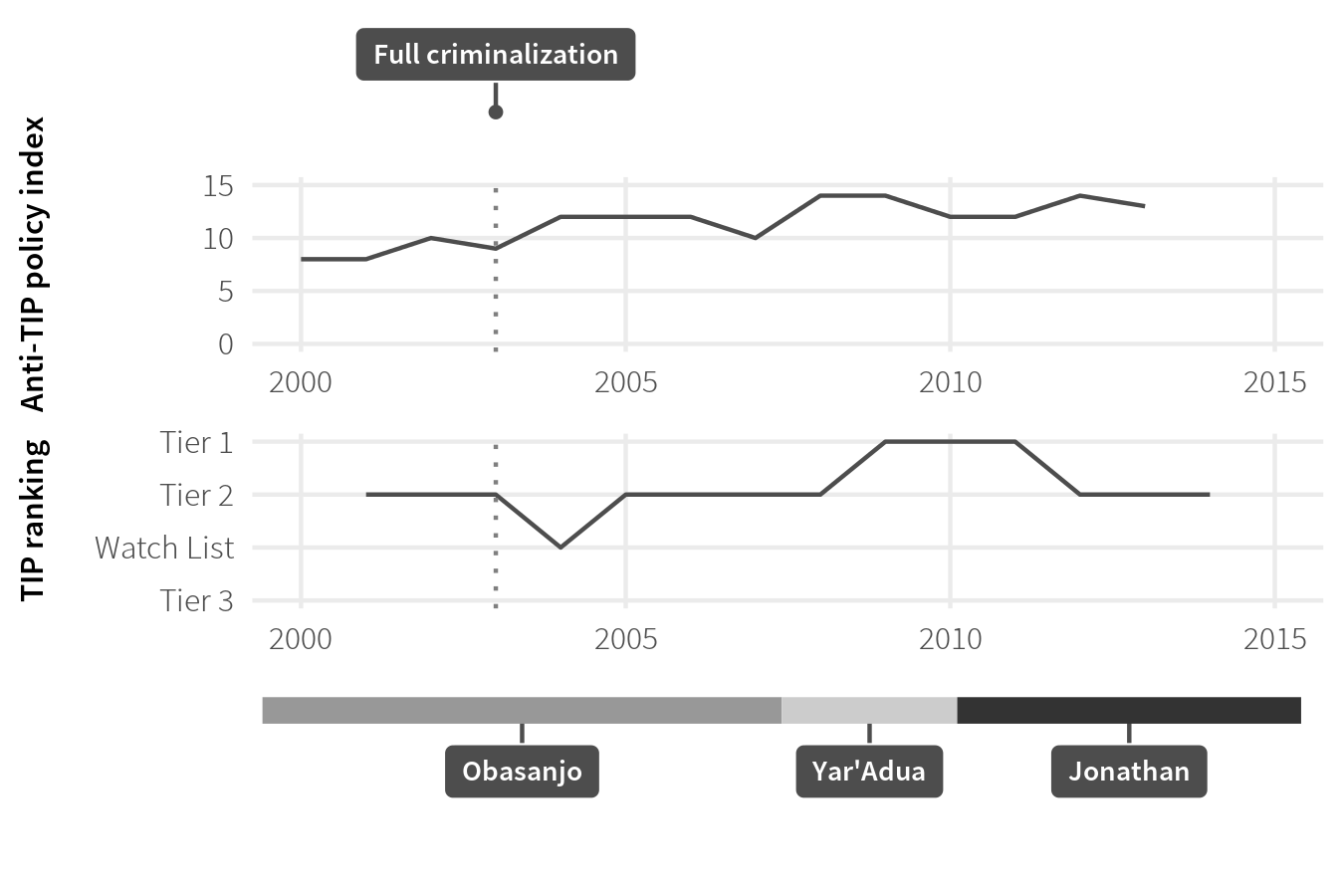

Figure 12: Nigeria’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2000–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $1,972.22 |

| Total aid | $50,490.19 million |

| Aid from US | $4,989.99 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 1.36% |

| Total TIP grants | $3,295,000 |

Table 12: Key Nigerian statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Indirect pressure

The US worked with both NGOs and IGOs to enhance the pressure and capacity for Nigeria to fight human trafficking. The embassy engaged with NGOs, for example visiting the Women’s Consortium of Nigeria (WOCON), which had long been doing anti-TIP work and which the US funded.2 Several times, the embassy met with TIP stakeholders in Abuja, “including foreign Embassies and NGOs,3 showing how the US was working with and through these other actors. The U.S. embassy and NAPTIP also developed a national stakeholders forum with relevant state working groups, in addition to domestic NGOs and international agencies such as UNICEF, USAID, ILO, and the IOM. The US also funded IGOs to carry out anti-TIP work, including the IOM anti-TIP training module for police recruits mentioned above.4 The US Department of Labor funded a regional study of child trafficking patterns in eight West African countries, including Nigeria.”5

Concerns

Nigeria was strongly motivated to earn a Tier 1 rating, because it saw trafficking in persons as an issue on which the country could earn a strong international reputation. To this end it held an international summit on trafficking in persons in 2002. Nigeria successfully worked to be seen as a regional role model on anti-TIP policy.6 The US DOS used Nigeria as a showcase example and the international media promulgated this idea. For example, on June 19th, 2009, a Christian Science Monitor’s editorial used Nigeria as example of how developing countries can take anti-TIP steps.7

To improve Nigeria’s Tier rating, the US worked closely with high-level officials to provide specific recommendations on TIP policy. In one one-on-one meeting, the embassy recounts that the Minister of Justice was thankful for the advice and “was fascinated by the list of Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 countries from the State Department website. He said Nigeria could certainly reach Tier 2 for the 2005 Trafficking in Persons Report. He added that his goal was for Nigeria to be a Tier 1 country.”8 In 2009, when Nigeria received a Tier 1 rating, officials were quick to take credit. The Nigerian newspaper This Day featured a story about NAPTIP titled “Human Trafficking, Worst Crime Against Mankind.” In it, NAPTIP Executive Secretary Simon Egede said that he was not surprised that the most recent TIP Report raised Nigeria to Tier 1 based on all the work of NAPTIP and previous Executive Secretary Carol Ndaguba.9

Nigeria was concerned with how criticisms on TIP might interfere with its reputation in the UN Human Rights council. In one October 2008 meeting, U.S. officials discussed trafficking issues with the Director of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs International Organizations Department Second United Nations Division. During the meeting, the director noted that Nigeria’s was preparing for its UN Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in February 2009 and worried how the criticisms in the TIP Report would affect their review. The embassy reported, “Ibrahim stated that the GON is ‘doing a lot to improve human rights’, but still receives negative reports such as the U.S Human Rights Report and the Trafficking In Persons (TIP) Report which will undoubtedly be cited during the UPR.”10

Outcomes

Legislation

Beginning in 1999, the Women Trafficking and Child Labour Eradication Foundation (WOTCLEF), an NGO founded by Amina Titi Atiku Abubakar, wife of Vice President Atiku, led civil society groups to sponsor an anti-trafficking bill. The TIP Report criticized Nigeria for lacking a comprehensive anti-TIP law right from the beginning. By the 2002 report, a federal legislation draft existed that was modeled on a law recently passed by Edo State, although the proposed legislation only addressed trafficking of women and children. In June 2002 the House of Representatives passed the anti-TIP bill, which the Senate then passed in February 2003, just in time for US reporting deadlines. The bill was signed into law in July that year, establishing the Nigerian Government’s anti-trafficking agency, the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP).

Despite passing the bill, Nigeria devoted few resources to actual anti-TIP policy. However, in September 2003 the President appointed Mrs. Carol Ndaguba as the first head of NAPTIP. “[This] sudden surge in Nigerian law enforcement efforts against child trafficking,” the US embassy wrote, “has drawn greater attention to the magnitude of this problem in the region while also reflecting improved political will to crack down on trafficking crimes in general.”11 The embassy noted its own efforts to encourage Nigeria to step up these efforts, and a cable describes the close relationship the U.S. and Nigeria were developing to combat trafficking. 12

Despite US praise for the new law and the new agency, the US continued to criticize Nigeria on enforcement issues. It downgraded Nigeria to the watch list in 2004 “because of the continued significant complicity of Nigerian security personnel in trafficking and the lack of evidence of increasing efforts to address this complicity.”13 The report also criticized Nigeria’s efforts to prevent trafficking, shelter and train victims of trafficking, and to prosecute traffickers and other involved parties. Indeed, the US itself was spending more than $3 million trying to bolster enforcement, including training prosecutors, law enforcements, and judicial officials, running rehabilitation shelters for victims, developing reports, raising public awareness, and more.14

The TIP law was amended in 2005 to increase penalties for traffickers. The 2005 TIP Report praised the many successes of NAPTIP including improved response and stronger efforts across the law enforcement spectrum, the increased federal and state efforts aimed at prevention, and the opening of a stakeholders forum where interested parties come together to discuss best practices and progress in anti-TIP efforts. However, the report also called out corruption among law enforcement and immigration officials.15

In the years to come, NAPTIP worked to enforce the law and succeeded in keeping the issue an ongoing priority. For example, Nigeria and Benin signed an important agreement to fight trafficking.16 In 2008 NAPTIP announced its TIP statistics at its annual stakeholder meeting showing that it had handled 587 cases of human trafficking for “sexual exploitation and child abuse” between October 2007 and May 2008. Furthermore, the agency convicted ten traffickers during the same period.17 Nigeria received a Tier 1 rating from 2009-2011, but in 2012 the US dropped Nigeria to Tier 2, citing stagnation in several areas including federal funding for NAPTIP, provision of protective services, victim reintegration, and maintenance of NAPTIP facilities. Nigeria has remained there since, its efforts ongoing, but with remaining room for improvement.

Institution building

The US supported institution building in multiple ways. In the early years, the Department of Labor funded an ILO-IPEC program that in turn funded efforts by the inter-ministerial TIP Committee to create a national plan against trafficking.18 The US worked closely with NAPTIP Executive Secretary Carol Ndaguba and many other high level anti-TIP officers19 and lobbied for more funding for strengthening NAPTIP.

With encouragement from the US,20 Nigeria’s TIP database became operative in September 2008. This NAPTIP project was sponsored by the American Bar Association’s Rule of Law Initiative and connected to all NAPTIP zonal offices. The solar powered main server provides 24-hour access and greater operational capacity to allow law enforcement and civil society across the country to collect and collate data in an effective and efficient manner.21

The US additionally supported institutional and capacity development. For example, the Department of Justice provided investigative training to Nigerian law enforcement agencies.22 The American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative (ABA-ROLI) also created a training manual for the immigration service and trained judges, prosecutors, and staff of many other government agencies.

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

The US engaged in efforts to educate police officers on the trafficking problem. USG officials met with police commissioners who lacked a basic understanding of TIP, and the embassy explained the distinctions between trafficker and victim, trafficking and smuggling, and so on. The US funded an IOM effort to add an anti-TIP training module to the basic training curriculum for new police recruits. 23 They also sent representatives from Nigeria’s civil society, government and media to attend U.S. programs on trafficking issues.”24 The ultimate impact of these efforts is difficult to assess, however.

Conditioning factors

Several factors worked initially against scorecard diplomacy in Nigeria. In the early years the influence of scorecard diplomacy was hampered by official complicity in trafficking and corruption. NAPTIP officials also claimed “a lack of resources limited their ability to act more aggressively.”25 In addition, in one 2002 cable, the US embassy also complains to Washington of a large Italian donation of resources, noting that such unconditional aid was hampering US efforts to exert leverage.26

However, as the years went by, the US and Nigeria developed a strong working relationship on TIP, a relationship that included a strong financial commitment from the US, which funded a wide variety of activities, training prosecutors, law enforcements, and judicial officials, running rehabilitation shelters for victims, developing reports, raising public awareness, and more.27 Progress occurred, facilitated by the embassy’s strong working relationship with NAPTIP leadership, especially Carol Ndaguba, who continued to be involved with NAPTIP after she stepped down. Another helpful factor was a desire for Nigeria to serve as a regional leader and to use its reputation on TIP to improve its reputation on human rights more generally, a role the US was quick to promulgate.

01ABUJA1921_a↩

04LAGOS300_a, 05LAGOS1401_a↩

09ABUJA326_a, 09ABUJA951↩

03ABUJA515↩

02ABUJA857_a↩

06ABUJA1518_a, 09ABUJA1437_a↩

The Christian Science Monitor’s Editorial Board, “A Stop Sign for Human Trafficking,” The Christian Science Monitor, 19 June 2009, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.csmonitor.com/Commentary/the-monitors-view/2009/0619/p08s01-comv.html.↩

04ABUJA1839_a↩

7/06/2009, This Day, “Roland Ogbonnaya, “Nigeria: Naptip – Human Trafficking, Worst Crime Against Mankind.”,” allAfrica, originally published on This Day, 5 July 2009, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://allafrica.com/stories/200907060237.html.↩

08ABUJA2048↩

03ABUJA1916_a↩

04ABUJA167_a↩

TIP Report, 2004↩

04ABUJA167_a↩

2005 TIP Report↩

Max Amuchie, “Nigeria, Benin Sign MOU On Child Trafficking,” allAfrica, originally published on This Day, 10 June 2005, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://allafrica.com/stories/200506130490.html.↩

08ABUJA1023_a↩

03ABUJA515↩

05LAGOS1891_a↩

07LAGOS193_a↩

08ABUJA1950_a↩

08ABUJA770_a↩

03ABUJA515↩

04ABUJA167_a↩

06ABUJA1518_a↩

A cable describing the situation ends with a scathing comment on Italy’s actions: “This has been a case study in how not to deliver law enforcement assistance in a country with a serious corruption problem. Aside from losing valuable leverage to prod the GON into adopting a more sincere and aggressive anti-TIP effort, the Italian Government has not helped our efforts to craft a smaller yet more focused and effective anti-TIP law enforcement project as the GON may now be reluctant to accept USG conditions on aid worth a fraction of the strings-free Italian largesse.” 02ABUJA358_a↩

04ABUJA167_a↩