Mozambique

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/mozambique/.

PDFContents

The collaboration between the United States and the government has been constructive. Tracking developments on domestic anti-TIP legislation shows the full arc of a country that at first has no anti-trafficking law to a country that passes this law and deals with the challenge of implementing it. Mozambique has been a prime recipient of U.S. anti-TIP assistance. The US technical assistance and consistent diplomatic engagement on the law was crucial to moving the law along in the legislative process. US engagement helped raise public awareness to the trafficking issue through public awareness campaigns, brought together key NGO and government players, and lobbied the government to take action.

The case of Mozambique illustrates the importance of the engagement components of scorecard diplomacy: education and assistance. From the beginning the Mozambican authorities (in addition to local NGOs and increasingly civil society) were conscious of the trafficking problem and eager to fix it, which facilitated cooperation with the US. The collaboration was practical, with the embassy engaging with the Director of Migration and the Mozambican military’s commander of border troops. The occasional meetings on TIP were typically high profile, involving the justice minster or targeting key players, and accomplished a great deal. Funding for all kinds of anti-TIP projects proposed by local actors as well as outside donors was consistent and recognized as influential.1

The case of Mozambique also highlights the importance of the local media in stoking the reputational concerns, the importance of cooperation with IGOs and NGOs in facilitating change, and the sensitivity to drops in tiers. On the downside, however, it also highlights the all too common implementation challenges for countries, especially those with scarce resources, and therefore the importance of scorecard diplomacy including not only monitoring and grading, but also practical assistance.

Background

Mozambique has a serious trafficking problem, especially along its border with South Africa, where men and boys are forced to labor in agriculture and extractive industries or as street vendors. Women and girls from rural areas are lured to cities on fake promises of employment or education, only to be exploited in domestic servitude and the sex trade. Children are often forced to work. Human and drug trafficking commonly co-occur.

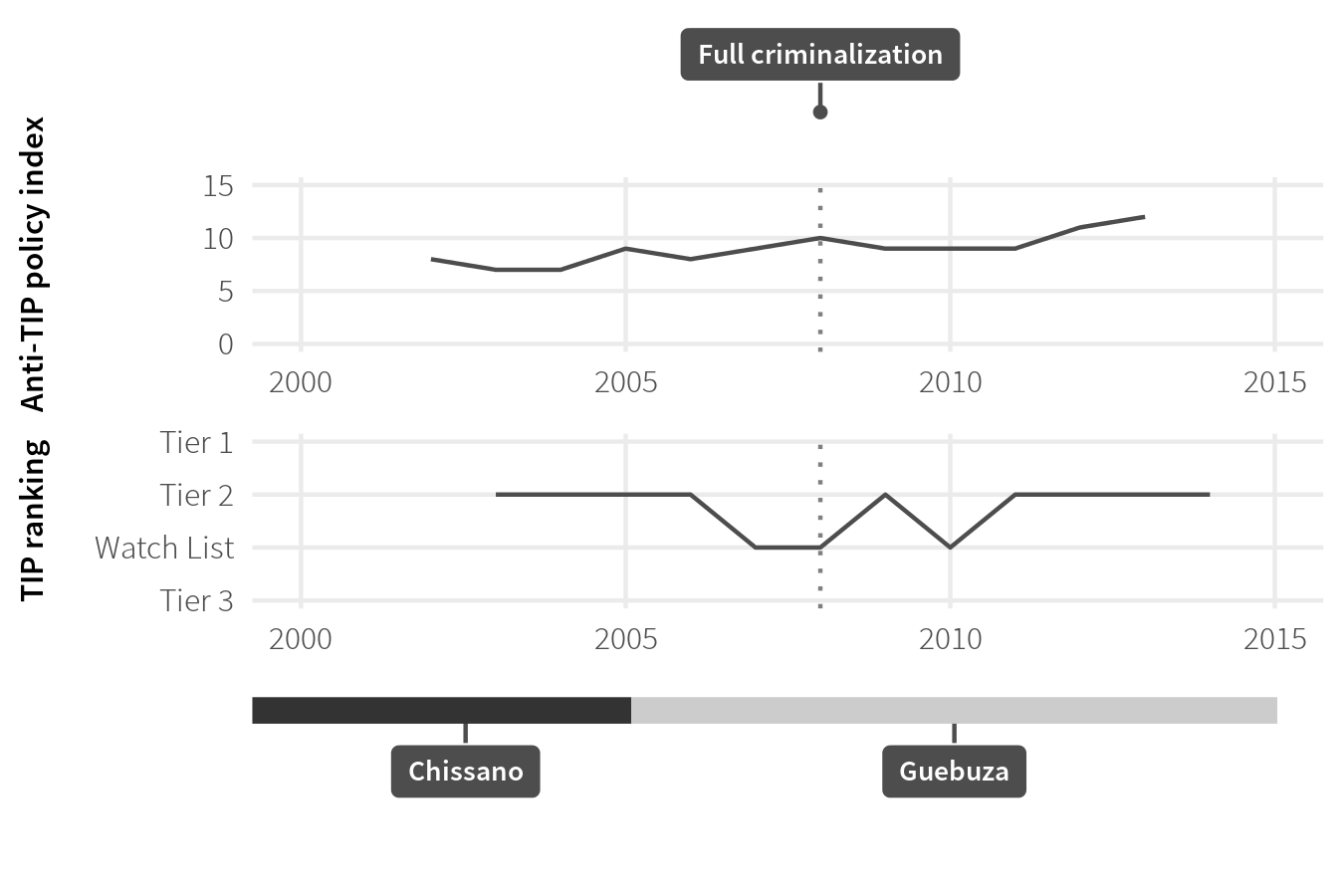

Figure 11: Mozambique’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2003–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $371.66 |

| Total aid | $28,911.12 million |

| Aid from US | $3,663.10 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 28.2% |

| Total TIP grants | $3,712,000 |

Table 11: Key Mozambican statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

Scorecard diplomacy meetings occurred regularly and with interactions at a high level, often ministers and also the president of the National Assembly, the Minister of Justice, committee leaders, chiefs of police and border patrol, other relevant ministers. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2003, when Mozambique was first included in the report. The cables that discuss TIP constitute 10 percent of the overall available cables, suggesting that TIP has been a top priority for the embassy. Scorecard diplomacy focused on providing technical assistance and diplomatic encouragement to pass an anti- TIP law and the embassy was active in the drafting process. The US also used meetings to push repeatedly for the implementation of the law to start. The US also supported construction of the Moamba Reception Center for TIP victims and encouraged communication between different stakeholders on TIP issues.

Indirect pressure

The media took a lead role in exposing TIP in Mozambique, and the embassy worked strategically with them.2 For example, during a visit from G/TIP Africa Reports Officer, the embassy arranged a lunch with a dozen local journalists who then filed stories on the interview for their newspapers outlining the problem in Mozambique and emphasizing the US efforts to help fight trafficking.3 Several trafficking cases received widespread coverage and increased attention to the problem.

NGOs have also amplified US efforts. After the US funded the upstart of the Moamba Reception Center, it introduced the NGO Save the Children Norway (SCN) and the Peace Corps to the project, in which they subsequently became involved.4 The US also funded an NGO, Rede CAME, to help disseminate the new law, training police, border guards, and judicial officials, and building synergy between civil society and the government5 Finally, the US worked closely with the IOM, providing them support in the drafting of the anti-TIP legislation,6 and funding an IOM research and capacity building program to strengthen civil society efforts to combat TIP and identify trafficking patterns.7 Thus, NGOs, IGOs, the media and the US were well synchronized. Scorecard diplomacy enabled media coverage and NGOs facilitated attention to trafficking.

Concerns

Although the government was cooperative, the interactions between Mozambique government officials reveal few explicit statements about their motivations for cooperating with the US. Progress appeared to be largely driven by media coverage, which suggests concern with domestic criticism. Meanwhile, suggesting the benefit of a good reputation on TIP, the embassy encouraged Mozambique to set an example for its fellow members of the SADC.8

Immediately following the unanimous passing of the anti-TIP law, the embassy reported that “USG technical assistance and consistent diplomatic engagement complemented the collaboration between the GRM and a determined civil society” and that “the USG’s growing financial assistance programs in the country also provided Post with significant leverage,” presumably resulting in “the GRM acting with uncharacteristic swiftness” in the closing months.9

Outcomes

Legislation

The US first included Mozambique in the TIP Report in 2003, when it gave it a Tier 2 rating and criticized the absence of an anti-trafficking law. Attention to TIP heightened drastically in March 2004 after allegations surfaced about trafficking in human body parts and child disappearances in northern Mozambique.10 The Head of the parliamentary bench for the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) called for an investigation and said the Assembly would take up anti-trafficking legislation.11 The minister of justice asked the ambassador for “country model” examples of existing TIP legislation that her committee could use as a guide. The embassy immediately sought to provide such technical assistance.12 After ministerial-level meetings, US-paid legal consultants were included on the team drafting the legislation. 13

When by 2007 the law had not progressed, the US dropped Mozambique to the Watch List and stressed the need for the law to pass before the tier could improve. The embassy chargé d’affaires met with the president of the National Assembly to encourage him to schedule the draft law for debate during the first legislative agenda of the year, because the agenda had been finalized without it. The chargé d’affaires urged Mozambique to become the first country in the South African Development Community (SADC) with a comprehensive law. In a clear example of US agenda-setting power, within a week, an addendum placed the law on the current agenda for discussion and the President of the National Assembly called the chargé d’affaires to assure him. The law was passed on April 10th that year, just in time to be included in the 2008 TIP Report.14 The embassy reported that the adoption of the law was the “result of a ‘perfect storm’ in recent months, including a constant lobbying effort by USG officials and civil society groups coupled with a highly publicized TIP case in March.”15

By February 2010 still no arrests had been made because implementing regulations for the 2008 Trafficking Law were still missing. The embassy offered technical assistance to complete these regulations.16 The 2010 TIP Report once again dropped Mozambique to the watch list, stressing the need for implementing legislation. By 2011, the regulations were in place and the government prosecuted and convicted trafficking offenders for the first time under the anti-trafficking law, increased prevention efforts, and trained local officials about legal remedies provided under the new law.17 Such efforts have remained steady since.

Institutions

After passage of the law, US efforts in Mozambique focused on strengthening key institutions, especially the judiciary and police force.18 Due to capacity issues, however, victim protection has remained weak and run mostly by NGOs. For this reason, the US has supported construction of the Moamba Reception Center, a shelter for TIP victims that was influenced by visits to ‘safehouses’ in the US.19 The US also contributed to informal institutions. For example, the embassy led a bimonthly forum for civil society, government, and the diplomatic corps to discuss trafficking issues.20 The USG also funded meetings between the Mozambican civil society and the Ministry of Justice to discuss the TIP legislation, and with the South African Legal Reform committee to discuss South Africa’s approach to drafting an anti-TIP law. These meetings boosted efforts to “knit together a tighter regional network of Southern African civil society organizations fighting the growing TIP problem.”21

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

The Moamba Reception Center for TIP victims was influenced by US practices. On cable describes how the co-director of the project, Lea Boaventura, visited the US in 2004 as part of an International Visitor Program. During the time in the US she visited several “safe houses” for trafficking victims and used part of what she learned there to design the Moamba Reception Center.22

Conditioning factors

US influence in Mozambique was facilitated by the government’s acknowledgement of the problem and its strong will to improve. The US also enjoyed great cooperation with NGOs and a supportive media environment. The media covered a couple of timely trafficking cases that helped bring attention to the issue and in general had strong coverage of trafficking. Furthermore, US assistance provided some leverage and interaction. The biggest challenges were the scale of the problem and the lack of resources and capacity for victim protection.

05MAPUTO378↩

08MAPUTO651↩

05MAPUTO1030, 08MAPUTO651, 06MAPUTO564, 07MAPUTO886↩

07MAPUTO1475↩

07MAPUTO464, 08MAPUTO651↩

04MAPUTO513_a. IOM was funded in 2005.↩

05MAPUTO114↩

08MAPUTO322↩

08MAPUTO322↩

04MAPUTO464_a↩

04MAPUTO464↩

04MAPUTO513↩

06MAPUTO564↩

08MAPUTO322. The passage was noted in the 2008 report.↩

08MAPUTO322↩

10MAPUTO163↩

2011 TIP Report↩

04MAPUTO168↩

05MAPUTO566↩

08MAPUTO261↩

06MAPUTO564↩

05MAPUTO566↩