Malaysia

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/malaysia/.

PDFContents

The US has had a strong influence on anti-TIP policy in Malaysia. The government of Malaysia (GOM) cared greatly about its Tier ranking, repeatedly expressing concern about their international reputation and asking how to obtain a higher ranking. Malaysia’s Tier 3 ranking on the 2007 TIP Report was a primary motivation in the passage of an anti-TIP law. The US also played a crucial role in getting the GOM to investigate allegations of trafficking of Burmese refugees to the Thai border by Immigration officials. The US funded and pushed for the building of shelters, served as an important advisor and liaison between anti-TIP actors, and provided well-received trainings. Each of Malaysia’s drops to Tier 3 received much media attention, which helped increase the pressure on the government to address US concerns. The US also collaborated with NGOs, particularly Tenaganita, and pushed the government to work more closely with NGOs. NGOs credited the US with motivating the government to change.1 While a rocky bilateral relationship impeded progress on TIP in the beginning, the relationship improved a great deal over the period reported in the cables, which boosted cooperation on TIP. However, the government continued to lag in the areas of labor trafficking and victim protection, so low ratings continued. The controversy surrounding Malaysia’s upgrade in the 2015 TIP Report despite little actual improvement reveals the weakness of the TIP Reports as a sometimes-biased grading system.

Overall, Malaysia illustrates the power or eliciting reputational concerns though scorecard ratings, the indirect pressure ratings generate, and the important collaboration with civil society, but also exposes the dangers of politicizing the ratings and the necessity of a strong bilateral relationship for scorecard diplomacy to function.

Background

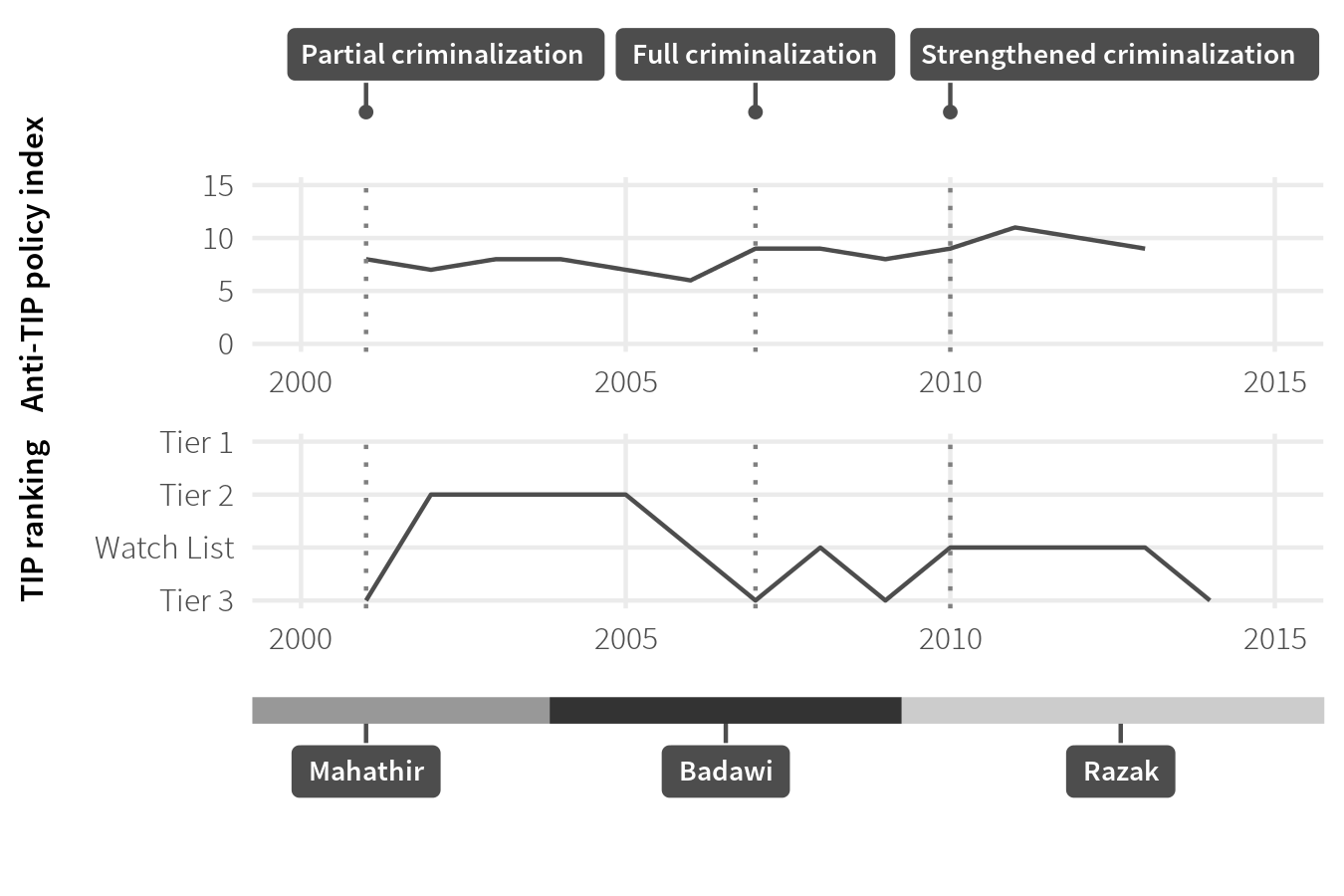

Malaysia is host to an estimated two million undocumented foreign workers in addition to as many documented foreign workers from various Southeast Asian countries. Many of these workers are vulnerable to exploitation and experience forced labor or debt bondage in factory or plantation work. Governmental regulations place the burden of paying immigration and employment authorization fees on foreign workers, which can put them into dependencies. Some employers withhold travel documents and deduct recruitment debt payments up to six months of wages or restrict workers’ movement. Some Cambodian women are subjected to domestic servitude. Young women, mainly Southeast Asian, are forced into prostitution after recruitment for other work or after entering into brokered marriages. In more recent years the situation of refugees and asylum-seekers has worsened and exposed them to trafficking. Large crime syndicates engage in trafficking, but there are also allegations of facilitation by some government officials. As Figure 10 shows, the tier rating has alternated between 3 and 2, reflecting the government’s on-going implementation problems. Since the mid- 2000s, improvements have occurred slowly.

Figure 10: Malaysia’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2001–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $8,447.42 |

| Total aid | $4,939.21 million |

| Aid from US | $1,164.50 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 0.194% |

| Total TIP grants | $968,140 |

Table 10: Key Malaysian statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

Scorecard diplomacy meetings on were frequent and with interactions occurring at a high level. These included the attorney general, several prime ministers, and several ministers and government officials from various ministries including the ministries of foreign affairs, home affairs, immigration, human resources, internal security, and Women, Family, and Community Development, as well as members of the police. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2006, although Malaysia was included in the report already in 2001. The cables that discuss TIP constitute 13 percent of the overall available cables – the highest of any of the case studies – suggesting that TIP has been a top priority issue for the embassy. Initially the diplomatic efforts had to focus on getting Malaysia to acknowledge the problem and help officials understand that trafficking could not be voluntary. Scorecard diplomacy also influenced the government’s understanding of labor trafficking and provided training about the treatment of victims. Scorecard diplomacy also focused on anti-TIP legislation and the embassy advised drafters in the attorney general’s office by providing them with US anti-trafficking legislation as well as references to other countries’ laws. The US also used tier ratings to push for action. At times the embassy was very hands-on. It encouraged the government to investigate allegations of trafficking of Burmese refugees to the Thai border by immigration officials and also provided training and brought in experts to talk to officials on implementing the new law. The US provided funding for training and pushed for the building of shelters, and generally sought to act as a liaison between anti-TIP actors.

Indirect pressure

Third party actors have augmented scorecard diplomacy in Malaysia. Media reports on TIP increased pressure on the GOM to address trafficking.2 The media coverage of the downgrading to Tier 3 in 2009 increased attention to the Report and prompted multiple officials to respond publicly to the ranking.3 The opposition party also used the negative press to criticize the government for the ranking.4

The media gave extensive coverage to the arrest of immigration officials in 2009, which boosted the US’s claims about the trafficking of refugees. One prominent newspaper published an entire interview with the US ambassador on TIP.5 When Malaysia was downgraded to Tier 3 again in 2014 for failing to improve services for victims, negative coverage exploded both inside and outside Malaysia, forcing the deputy home minister on the defensive in The Guardian.6 Thus the media strengthened the US’s efforts in Malaysia.

Civil society has also been essential to US efforts. The US collaborated with civil society organizations, particularly NGO Tenaganita, which ran US-funded TIP shelters. Tenaganita’s relationship with the government was somewhat strained; its director was a member of the opposition party.7 The US nonetheless succeeded in pushing the government to collaborate more with NGOs in their anti-TIP work.8 In “a major breakthrough,”9 Tenaganita and another NGO were included in the new Legal Committee of Anti-Trafficking in Persons. Some Catholic civil society groups attributed the increased willingness to work with NGOs to the 2009 Senate Foreign Relations Report…and the Department’s June TIP Report. 10 Thus, the embassy helped bridge the gap between the government and civil society, allowing NGOs to reinforce the US message.

Concerns

Malaysia has expressed concern about its poor rankings and repeatedly asked how to improve to get upgraded.11 Some of this concern has been about the ramifications for the bilateral relationship, partly because the US itself invoked TIP as important to the relationship. 12 Shortly after the release of the 2007 TIP Report Tier 3 rating, the ambassador warned the prime minister that “a negative interim report could negatively affect military exchanges and other non-trade related programs.” This warning did not go down well with the prime minister, who responded that “… the U.S. was the only country that ‘passed judgment on and punished’ other countries on issues like this. ‘This is a great source of discomfort in our bilateral relations,’ he added, ‘as no country likes to be judged.’” Turning the tables, he said the ranking made Malaysian officials “‘very uncomfortable’” and, while noting that Malaysia had a TIP problem, warned in turn that the issue could “complicate” other aspects of the bilateral relationship that were improving, such as a military arms deal that the two countries were close to closing.13 The poor rating thus put the bilateral relationship on the edge. Officials did not want to appear publicly as if they were feeling pressured by the US. In follow up visits, one official stated flatly that Malaysia did not care about possible loss of aid, yet he was keen to explain what steps Malaysia was taking to follow up on US recommendations. At the same time, he advised against a visit by TIP Ambassador Mark Lagon to avoid the appearance of caving to the Americans. 14 Underscoring that the anger at being ranked Tier 3 in 2007 was not just due to concern about aid or bilateral relations but also about image, in another meeting, the foreign minister fretted to the US ambassador that the report “‘affects our country’s reputation and dignity.’”15

The reaction after the 2009 Tier 3 ranking was much more constructive.16 A UNHCR representative said Malaysia had begun to allow the UNHCR to screen migrants and described this progress as a “‘crusade to please their critics.’” It was rumored that the new prime minister had hired a public relations firm, which suggests that once again the GOM was concerned about its public image.17 Not only did officials seem to care about Malaysia’s image, they also seemed concerned about not having an image that they were caving to US pressure. Although NGOs told Ambassador CdeBaca that the Tier 3 ranking was motivating the government,18 the foreign minister told him that the Tier ranking was “‘the least of (his) concerns’ and that the GOM’s actions were not to prove themselves to another country but done simply because “it is the right thing to do.”19 Nonetheless, the foreign minister’s newfound enthusiasm and keenness to tell the ambassador about all the actions the government was taking (including inviting the embassy to sit in on high-level TIP meetings) suggests keen attention to the tier rating. Indeed, even the concern that the government’s actions not be perceived as submitting to US pressure signaled great concern with the government’s image. Certainly, showing that a rating can matter for domestic legitimacy, the opposition party used the ranking as political ammunition against the government, so there was every reason to protect the government’s image.20

Malaysia especially cared about its appearance compared to neighboring countries, asserting that Malaysia did not deserve a lower ranking than other countries with worse trafficking problems.21 The US took advantage of the governments concern with its placement vis-à-vis others, several times telling officials that South Korea had been able to quickly rise from Tier 3 to Tier 1 by taking strong action on TIP.22

In sum, it seems likely that the government’s motivation was a mix of concerns about image as well as about practical fallout from a poor rating in terms of bilateral relations. Interestingly, the image concerns were both about the “dignity” of the country, but also about the government’s image domestically.

Outcomes

Legislation

One of the most significant outcomes the US produced was the passage of a comprehensive anti-TIP law. From the beginning, TIP Reports criticized the lack of an anti-TIP law, which left victims to be treated as illegal migrants.23 When, in 2006—after Malaysia was downgraded to the watch list—the government considered whether to pass a new anti-TIP law or amend existing laws, the US pushed for a new law.24 While some ministries expressed support, the Attorney General (AG) resisted, saying, “‘we are tired of this issue.’” He disliked the US pressure to pass a law, telling the embassy, “‘if we pass a law, it is just a process to raise our status from Tier 3 to 2 to 1,’” for he believed existing laws were sufficient.25 Existing legislation was not, in fact, adequate; traffickers were not being caught and victims were not being identified and protected.26 While the police, Immigration, foreign embassies, and NGOs were on board to combat trafficking, cabinet ministries were not nearly as involved and stonewalled the embassy.27

Nonetheless, the US sustained its lobbying effort, and eventually the AG told the ambassador that he was drafting a new comprehensive law. The bill progressed quickly, and the embassy remarked, “Persistent, action-oriented and behind-the-scenes diplomacy have produced results…and allowed the Malaysians to claim the anti-trafficking issue as their own priority.”28 The bill passed in May, and though imperfect, the embassy praised it for exceeding minimum standards.29 Scorecard diplomacy seemed to have played a heavy hand. Not only did the embassy point to its own “action-oriented and behind-the-scenes diplomacy,”30 the Prime Minister, notably, the prime minister directly linked the passage of the law to the TIP Report, telling the press, “I’ve read the [TIP] report. We did whatever we could, but it was not enough. That’s why we decided the (anti-TIP) bill was necessary.”31 The AG later confirmed this sentiment.32 In addition, officials said that Malaysia would ratify the Palermo Protocol, which it had previously resisted.

The 2007 TIP Report nonetheless downgraded Malaysia to Tier 3. The May passage of the anti-TIP law was too late to adjust the Tier rating, and furthermore, the US wanted to keep up pressure on implementation. It criticized the government for, among other things, poor treatment of victims and not fulfilling their promise to open a shelter. The ranking upset the government, but it enabled the US to keep up pressure to enact the new law and create the TIP commission it outlined.33

The embassy kept up diplomacy both towards the government and as intermediary to the State Department.34 It encouraged the DOS to reward Malaysia for progress to increase US credibility and stimulate re-engagement with senior officials,35 while reminding officials that the 2008 ranking would depend on implementation of the TIP law. 36 To facilitate this, the US provided significant training and, in response to repeated government requests, brought in experts to advise officials on implementing the new law.37 Although the US upgraded Malaysia to the watch list, the 2008 report still pressed for more investigations and prosecutions of forced labor incidents, something the embassy discussed with officials.38 In December, the government convicted the first trafficker under the new law.39

Another important case that drew in the US was the involvement of low-level Immigration officials trafficking refugees from Myanmar to the Thai border using official government vehicles.40 The problem attracted the attention of the US Senate, which the embassy said focused the attention of senior officials.41 The ambassador wrote both the minister of foreign affairs and the minister of home affairs to press for action, and the embassy spoke with others in the anti-TIP Secretariat.42 By mid-November, the government began to investigate the allegations43 and expressed willingness to participate in a contact group proposed by the Thai Government. Although communication between the US and the government on the issue intensified,44 the government kept delaying and tried to save face and control the situation by warning a journalist to “‘be patriotic’” by not reporting on the issue.45

Stressing implementation once again, the US dropped Malaysia back to Tier 3 in 2009, and pushed for increased prosecutions and convictions, particularly related to allegations of Immigration officials trafficking Burmese refugees across the Thai border.46 The ambassador stressed that engagement was key to raising the Tier status.47 Soon thereafter, nine people, five of whom were Immigration officials, were arrested for supposed involvement in a TIP syndicate, marking the government’s first acknowledgment of immigration official involvement. 48 Shortly after, the government asked for US law enforcement assistance with traffickers in the case who were residents of southern Thailand.49 The efforts helped, and by early August, NGOs told the embassy “that trafficking of Burmese refugees to the Malaysia-Thai border had declined recently. The government also announced that immigration officials in contact with refugees would be rotated regularly.50 The Director of UNHCR Malaysia told TIP ambassador CdeBaca that “trafficking of people to the…border had effectively come to a halt.”51 The opposition party credited the Senate report and TIP Report for revealing the exploitation of Burmese refugees, as well as NGO Tenaganita for its efforts. 52

Still, implementation was mixed. While the Thai border case evolved, another high-profile case surfaced. A recruiting agency was holding 140 Bangladeshi workers against their will, but the government treated the case as a labor dispute, because it “did not want to admit publicly that the case involved trafficking because of the large number of victims, and the government was not yet prepared to address the broader labor trafficking issues.”53

US pressure and mixed Malaysian efforts to respond continued. 54 The GOM informed the embassy that Parliament planned to amend the Anti-TIP law so the Labor Department would be able to make TIP prosecutions. After the amendment passed in November 2010,55 Malaysia made its first arrests for labor trafficking56

Pleased with implementation efforts, 57 the State Department upgraded Malaysia to the Watch List in 2010.58 The road since then has been rocky, however. Malaysia only avoided an auto downgrade in 2013 and 2014 because it received waivers, and by 2014 the US had to downgrade Malaysia to Tier 3. Thus, although the US was influential in Malaysia in getting the law passed, and implementation picked up on sex trafficking cases. On labor, however, despite a few victories and some progress, efforts continued to lag.

Institutions

The US also contributed to institution building. The US-aided anti-TIP law created a Council for Anti-Trafficking in Persons.59 After the release of the 2009 TIP Report, the GOM created the “Legal Committee of Anti-Trafficking in Persons,” including officials from various GOM departments and two NGOs. This was the first time the government had included NGOs on this level of TIP engagement.60

The US was also involved with the creation of victims’ shelters, funding the first shelter with the IOM and Tenaganita in 2006.61 The embassy repeatedly pressed the government to open its own victims’ shelter,62 and after the 2007 TIP Report called out the government for failing to keep past promises to build shelters, it finally opened three women’s shelters.63 The US also pushed for shelters for men, and the government discussed shelter operations with the US embassy.64 Still, problems remained, partly because the government would not fund the better NGO shelters and instead insisted that victims stay in government-run shelters that resembled detention centers. 65 A training in 2009 that compared government and NGO shelters stimulated “a spirited discussion on how Malaysia cares for the victims of trafficking.” Many participants told the facilitator “that they had never considered how placing victims into a detention-style facility might affect them” and requested training on running TIP shelters.66

The Malaysian government was generally very receptive to US trainings67 and invited US officials to explain how the US handled cases.68 NGOs supported the US training efforts. 69 In an August 2009 meeting, one state official said that the US workshops “gave him talking points on TIP to pass to…legislators.”70

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

In the earlier years, some officials did not believe Malaysia had a serious trafficking problem.71 Some did not understand the definition of trafficking72, and even in later years, the US had to stress the difference between trafficking and smuggling.73 The US helped change the government’s understanding and approach to TIP through meetings and trainings, getting officials to recognize the TIP problem and trying to change their views about the definition of TIP, particularly labor trafficking.

The US provided templates for the content of the legislation and helped reduce misconceptions of trafficking. Notably, when the AG decided to take up the legislation, he misunderstood the concept of trafficking as something that could be voluntary. This was evident as he “boasted that he would ensure the legislation ‘would extend the meaning of victims to include those who have voluntarily trafficked themselves.”74 In response, the embassy provided the AG office with language of anti-TIP laws of the US and other countries.75 By 2009 officials were acknowledging and taking more responsibility for TIP.76

For a long time, the Malaysian government preferred to approach forced labor issues merely as labor disputes.77 The US provided information on the US definition of labor trafficking in 2008.78 By the second half of 2009, some officials openly recognized labor trafficking.79 Other officials, however, were less receptive. In one meeting, the Director General of Labor commented that reports of maids running away from employers a few days after they had footed the bill to bring them to the country was a bigger issue than the domestic servant abuse: “I know you do not want to hear it, but keeping their passports prevents them from running away.”80 Eventually, however, the government accepted the US emphasis on labor trafficking. It started making some arrests 81 and amended the Anti-TIP Act to include labor or services obtained through coercion to the definition of trafficking. Still, as noted above, enforcement has severely lacked.

In sum, while trafficking remains a huge challenge in Malaysia, the US efforts have made major inroads on educating and socializing officials and law enforcement personnel into accepting the TIP problem, refining the definition to align with US and international preferences, and transmitting norms about shelters and victim protection.

Conditioning factors

US influence in Malaysia was facilitated by Malaysian concern about image and practical fallout in the bilateral relationship, as well as by active NGOs and strong media coverage. In addition, the influence was conditioned by the nature of the bilateral relationship, the varying presence of key interlocutors, divergences in understanding in TIP norms, and the official complicity in human trafficking.

In the early years of the TIP Report, the bilateral relationship was strained and characterized by mistrust.82 After the release of the 2007 TIP Report, anti-American sentiments among the Malaysian public hindered TIP progress by making it hard for the government to be seen as caving into US pressure. However, things improved towards the end of Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi’s administration, when, during the second half of 2008, ministries were encouraged to exchange more information on TIP with the US,83 and the prime minister told the Ambassador that “he anticipated a ‘very constructive relationship’ with the incoming U.S. administration.”84 A more careful US diplomatic approach helped overcome the government’s anger from earlier confrontations.85 The improved relationship was also accompanied by more convergence on the understanding of trafficking with the election of Prime Minister Najib Razak, who “took pains to distinguish between people smuggling and trafficking.”86 Still, understandings proved difficult to move; the 2010 amendments to the Anti-TIP Act added labor or services obtained through coercion to the definition of trafficking but still conflated trafficking and smuggling.

In addition to the gaps between the US and the Malaysian government both politically and on definition, the US also lacked what normally would be a key ally on TIP in the Ministry for Women, Family, and Children’s Development (WFCD). Indeed, the embassy reported that Minister Shahrizat Jalil often refused to engage and was hostile towards the US.87 After the 2007 Tier 3 rating, she “declined to meet with the embassy.”88 When Ng Yen Yen replaced Shahrizat as minister from 2008 to 2009, the relationship improved. She sought guidance on how to improve the rating, invited the ambassador to tour shelters, and welcomed a visit by TIP Ambassador Lagon. The embassy recognized a new “opening for engagement,”89 which lead to discussions on several issues, including labor trafficking and collaboration with NGOs on creating a TIP awareness program, as recommended by the US the prior year.90 The embassy noted, “We have come a long way since the Women’s Ministry (and other GOM offices) severed substantive contact on TIP issues with the embassy in the wake of the 2007 Tier 3 ranking, which left us without access during the critical launching period of Malaysia’s anti-TIP law.”91 Unfortunately for this new relationship, in 2009 Shahrizat returned as minister, although she was more prepared than before to work with the US to improve Malaysia’s Tier rating.92

09KUALALUMPUR775↩

09KUALALUMPUR152, 09KUALALUMPUR521↩

09KUALALUMPUR491, 09KUALALUMPUR632↩

09KUALALUMPUR491↩

09KUALALUMPUR632↩

Kate Hodal, “US Penalises Malaysia for Shameful Human Trafficking Record,” The Guardian, 20 June 2014, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/jun/20/malaysia-us-human-trafficking-persons-report.↩

09KUALALUMPUR906. Coorlim, Loof. “Human Trafficking: U.S. Downgrades Four Countries in TIP Report.” CNN. N.p., 20 Jun. 2014. Web. 20 Mar. 2015. http://thecnnfreedomproject.blogs.cnn.com/2014/06/20/human-trafficking-u-s-downgrades-four-countries-in-tip-report/↩

7/15/2009: 09KUALALUMPUR583↩

7/17/2009: 09KUALALUMPUR596↩

1/27/2010: 10KUALALUMPUR58↩

08KUALALUMPUR481, 08KUALALUMPUR955, 09KUALALUMPUR521, 09KUALALUMPUR775↩

08KUALALUMPUR880↩

07KUALALUMPUR1145↩

07KUALALUMPUR1145↩

07KUALALUMPUR1375↩

09KUALALUMPUR596↩

09KUALALUMPUR652↩

09KUALALUMPUR775↩

09KUALALUMPUR775↩

09KUALALUMPUR491↩

09KUALALUMPUR888↩

09KUALALUMPUR583↩

TIP Report 2004↩

06KUALALUMPUR1661↩

06KUALALUMPUR2160↩

06KUALALUMPUR2160↩

06KUALALUMPUR2160_a↩

07KUALALUMPUR753↩

07KUALALUMPUR834↩

07KUALALUMPUR753_a↩

07KUALALUMPUR1290↩

09KUALALUMPUR583_a↩

07KUALALUMPUR1145↩

07KUALALUMPUR1236↩

07KUALALUMPUR1290↩

07KUALALUMPUR1568↩

07KUALALUMPUR1557, 08KUALALUMPUR97↩

08KUALALUMPUR940↩

TIP Report 2009↩

08KUALALUMPUR495↩

08KUALALUMPUR799↩

08KUALALUMPUR934, 08KUALALUMPUR955↩

08KUALALUMPUR1017↩

09KUALALUMPUR79, 09KUALALUMPUR140, 09KUALALUMPUR245, 09KUALALUMPUR414, 09KUALALUMPUR459, 09KUALALUMPUR484↩

09KUALALUMPUR934↩

TIP Report 2009↩

09KUALALUMPUR583_a↩

09KUALALUMPUR600↩

09KUALALUMPUR609↩

09KUALALUMPUR704↩

09KUALALUMPUR775↩

09KUALALUMPUR846↩

09KUALALUMPUR152↩

09KUALALUMPUR863, 09KUALALUMPUR1025↩

10KUALALUMPUR58↩

TIP Report 2010↩

10KUALALUMPUR94↩

TIP Report 2010↩

07KUALALUMPUR1568↩

09KUALALUMPUR596↩

06KUALALUMPUR372↩

06KUALALUMPUR2035↩

TIP Report 2008, 08KUALALUMPUR1017↩

08KUALALUMPUR1110, 09KUALALUMPUR609, 10KUALALUMPUR58↩

TIP Report 2010, 2011, 2012↩

09KUALALUMPUR1025↩

06KUALALUMPUR372, 09KUALALUMPUR704, 09KUALALUMPUR832↩

09KUALALUMPUR775, 09KUALALUMPUR652, 08KUALALUMPUR1073↩

09KUALALUMPUR835, 09KUALALUMPUR934↩

09KUALALUMPUR906↩

06KUALALUMPUR1948↩

06KUALALUMPUR2160↩

09KUALALUMPUR521, 09KUALALUMPUR618↩

06KUALALUMPUR2297↩

07KUALALUMPUR653↩

09KUALALUMPUR934↩

09KUALALUMPUR906↩

08KUALALUMPUR200↩

09KUALALUMPUR521, 09KUALALUMPUR753, 09KUALALUMPUR830↩

10KUALALUMPUR6↩

TIP Report 2010↩

07KUALALUMPUR1145↩

08KUALALUMPUR1073↩

08KUALALUMPUR1026_a↩

08KUALALUMPUR340, 09KUALALUMPUR597↩

09KUALALUMPUR597↩

06KUALALUMPUR2160↩

08KUALALUMPUR448↩

08KUALALUMPUR448, 08KUALALUMPUR1073↩

08KUALALUMPUR1110↩

09KUALALUMPUR230↩

09KUALALUMPUR981↩