Kazakhstan

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/kazakhstan/.

PDFContents

The case of Kazakhstan highlights the importance of reputational concerns in providing an opportunity for scorecard diplomacy to be influential. Although Kazakhstan has struggled to establish its democratic credentials and been unwilling to conform to many democratic expectations, it has vied for international approval. Officials have been keen to portray the country as modern and deserving of membership in the international community and the associated clubs, such as the OSCE. This desire for recognition gave the US and others an opening to influence TIP policy. Kazakhstan is also an important partner for the US in Central Asia. The embassy worked closely with NGOs, IGOs as well as national authorities and was able to influence outcomes significantly.

The case demonstrates influence on legislation, norms and institutions through several of the features of scorecard diplomacy, most notably how the ratings and concern for reputation incentivized the government, as well as the importance of engagement with NGOs and individual stakeholders within government. The case also illustrates the importance of international reputational concerns as well as engagement and practical assistance as constructive companions of scorecard diplomacy ratings.

Background

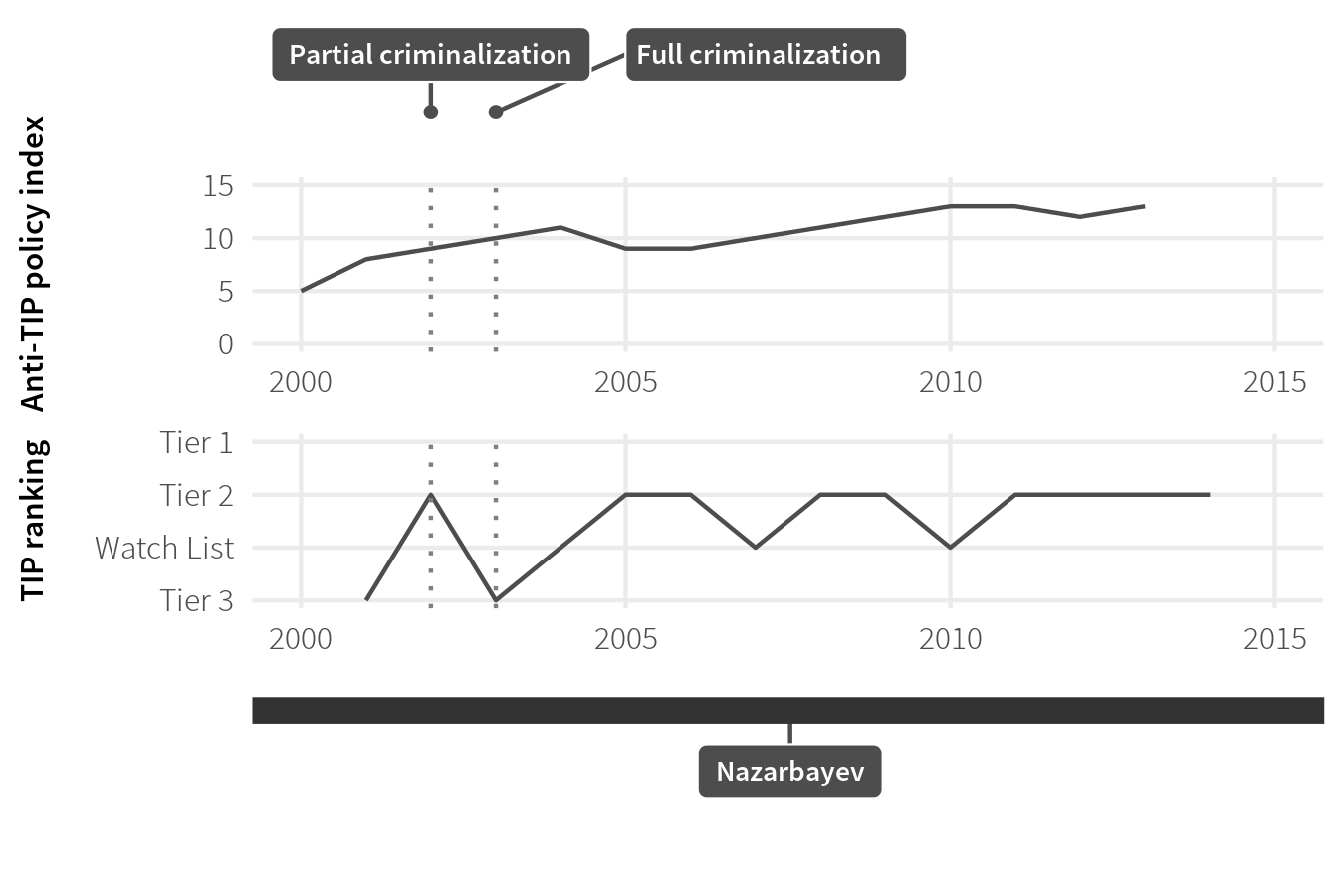

Kazakhstan was first seen as a country of origin and transit for young women trafficked, primarily for prostitution to the United Arab Emirates, Greece, Turkey, Israel, and South Korea. Over the years it’s also come to seen as a destination country, and most identified victims are trafficked domestically. Central Asian nationals are used for forced labor in domestic service, construction, and agriculture in Kazakhstan. Most of the identified victims are domestic although victims also come from neighboring Central Asian and Eastern European countries. Traffickers lure young girls and women from poor rural areas to large cities with promises of work as waitresses, models, or nannies. Children are also forced into begging, crime or pornography. Kazakhstan was initially rated Tier 3, but have made steady progress, as shown in Figure 9, below.

Figure 9: Kazakhstan’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2000–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $7,952.06 |

| Total aid | $15,063.58 million |

| Aid from US | $954.94 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 0.92% |

| Total TIP grants | $7,554,219 |

Table 9: Key Kazakhstani statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

Scorecard diplomacy meetings to discuss TIP were a high priority with interactions occurring at a high level, often with ministers such as the prime minister, the minister of justice, the minister of internal affairs and the foreign minister. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2005, although Kazakhstan was included in the report already in 2001. Despite this, the cables that discuss TIP constitute 5 percent of the overall available cables, suggesting that TIP has been a priority issue for the embassy, which sought to cultivate strong interlocutors and facilitate cooperation among different stakeholders. Scorecard diplomacy included basic education efforts such as trips abroad for officials and training of religious leaders in trafficking. The embassy was also encouraging the creation of a domestic TIP- policy infrastructure. The embassy was very involved in anti-TIP legislation. It met with officials to discuss minute details and monitored progress very closely by attending the inter-agency TIP working group. The embassy also has had ongoing dialogues about implementation issues and the US has provided several TIP grants.

Indirect pressure

Indirect pressure has been an integral part of US scorecard diplomacy in Kazakhstan. US cooperation with the OSCE and the IOM has reinforced US efforts. The high level of engagement in the legislative drafting by the US, but also by the IOM and OSCE – both with US funding –, helped spread the ideas and norms of TIP legislation by building a “cadre of experts.”1 The US has funded the IOM to collect and analyze non-official TIP statistics, in part through the information obtained through the NGO network funded by USAID.2 Throughout 2006-2007, the US Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) funded several IOM projects including training of law enforcement officials, awareness-raising, and an educational campaign.3

US efforts also facilitated cooperation among different stakeholders when, in March 2006, the US and IOM conducted a round table with NGO representatives and mid-level government officials from multiple state agencies,4 cooperation that continued the following year.5 In April 2007, the embassy’s INL office hosted a Donor Coordination Meeting with government officials and participants from the IOM, UNDP, UNODC, UNICEF, and the OSCE, among others, which became a springboard for future cooperation.6 Former Ambassador Napper also notes that he formed a link to NGOs: “Whenever I would travel I would always meet with NGOs and I’d meet with them about the legislation.”7

Concerns

Image concerns were important for Kazakhstan. The US TIP report gained prominence during a time when Kazakhstan was keen to improve its reputation in hopes of gaining the OSCE Chairmanship in 2009, for which it had bid (a goal finally attained in 2010).8 Between the chairmanship, which was awarded in 2007 for 2010, and the energy sector, the embassy reported that Kazakhstan had “confidence on the international stage.”9

In general the relationship was very hands-on. The US has provided lots of assistance and the government has been keen to cooperate. The reaction to the downgrade to the Tier 2 watch list in 2007 was typical; the Ministry of Justice Office Director thanked the US for the law enforcement training grants, encouraged future cooperation on victim assistance, expressed desire to learn from other cases, and asked the embassy to be specific about how Kazakhstan could improve its TIP rating.”10

Outcomes

Legislation

TIP was not a big priority for the government in the late 1990s. In 1999 the Government’s National Commission on Women’s and Family Issues even declined to include trafficking in its list of priorities. The first TIP Report came out in the summer of 2001 and placed Kazakhstan in Tier 3. Larry Napper, the US Ambassador from 2001 to 2004, recalls intense reactions and interactions with high-level officials. Initially the government thought they could get by with cosmetic changes. In February 2002, just before the reporting deadline for the US TIP Report, the government amended a temporary measure to the criminal code to cover trafficking of adults. It also initiated training programs for law enforcement and began to conduct random investigations of travel agencies promising work abroad. Finally, the head of the President’s Commission on Women and Family was appointed as government anti-trafficking coordinator. Implementation was severely lacking, however.

Ambassador Napper reports that during this time he was very involved with the legislation and that the inter-agency working group became serious about the law mainly because of the pressure of the US TIP Report:

They initiated that after we had engaged on the political level. It was not something that I could have got [the Minister of Justice’s] attention on. We would go up to Astana and meet with the Minister of Justice and meet with his team. First order of business was to get the legislation right. … We went up and discussed it in conceptual terms, walked through the kind of legislation we wanted to see; we went into it in very fine detail. They undertook to take it to the parliament. We monitored it very closely. I’d go and talk with parliamentary deputies about it and I’d mention the TIP legislation. … At the time that they were actually doing the legislation I would go up two or three times within the month or so. We worked on it together.”

After the 2004 report came out the government began to draft amendments to improve the anti-trafficking legislation. The US, along with the IOM and OSCE, attended the interagency TIP working group and was involved in the discussion of the draft amendments.11 In April 2005, the Law on Social Assistance, which the US had urged the government to pass in the 2004 TIP Report, was passed, providing a mechanism that allowed the government to provide grants to NGOs.

The spring of 2006 brought considerable progress. In February Parliament passed legislation to provide identified victims with temporary residence status to ensure their safe repatriation or participation in trafficking prosecutions. On March 2nd, 2006, in time for the annual TIP Report update from the embassy to Washington, the TIP amendments were finally enacted, and on April 10, the “2006 - 2008 National Plan of Action to Combat TIP.” Nonetheless, in 2007 the US placed Kazakhstan on the watch list because its efforts to prosecute and convict traffickers had ground to a near halt, with only one conviction in 2006 as opposed to 13 the year before. The US also criticized Kazakhstan for not doing more to provide victim assistance and protection.12 After this, the embassy met several times with the Director of the Ministry of Justice Office, and in response to a request of what specifically needed to be done, delivered a set of written recommendations from the US. Data sharing increased in advance of the interim assessment.”13 A case that led to a set of successful arrests and convictions later that year was lead by a person trained through Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) courses.14

After 2008 Kazakhstan has consistently been rated Tier 2 (with the exception of 2010 when it was on the watch list) and showed some progress on several issues including assistance to victims.15 In 2010 the TIP Report raised the issue of the forced use of children in cotton and tobacco harvest and cited this as the main reason for the downgrade. Kazakhstan has made some efforts to address this issue, but it persists,16 as do many of the other trafficking problems in the country.

Institution building

The US helped build domestic TIP infrastructure. The biggest effort was the creation of the anti-TIP center in Karaganda to train police and MVD officers, and hold roundtables to discuss TIP issues. The US Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) heavily supported its operation even influencing course content.17 Through a strong relationship with several key individuals within the Ministry of Justice, the US was able to incorporate several recommendations into the National Action Plan.18

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

The US fostered socialization and learning through training in the anti-TIP center in Karaganda and high-level exchanges between countries. For example, when officials asked for information on how to protect and assist victims, the US actually sent a Kazakhstani interagency delegation to Rome to study how the Italian government and Italian NGOs protect TIP victims. Once home, the officials implemented the lessons learned into domestic structures.19 Similarly, when the Chief of the Organized Crime Division suggested establishing an anti-trafficking interagency in a South Kazakhstan oblast, he said he had been inspired after attending a US professional exchange program in Houston where he saw a similar group and interacted with the local sheriff’s office.”20 Thus, US efforts were linked to the diffusion of an institutional format. The US even conducted a three-year program to train religious leaders in trafficking issues to promote local tolerance for returning victims of sex trafficking.21

Conditioning factors

A persistent obstacle for the effectiveness of scorecard diplomacy in Kazakhstan was government complicity in trafficking problems. However, this was countered by a desire to impress the US and the West and the fact that the embassy developed a strong relationship with key interlocutors. In addition, the US also had a strong relationship with Kazakhstan of practical assistance and training, which provided opportunities for interaction and influence.

The Kazakhstan case thus displays many of the elements of scorecard diplomacy: engagement with NGOs and individual stakeholders within government, the use of Tier ratings to incentivize the government, the influence on the legislation and other outcomes, the contribution to the definition of norms embedded in legislation and the efforts to socialize officials into these norms via training and exchanges, the contribution to domestic institution building and data collection, and the facilitation and coordination of other actors such as IGOs.

05ALMATY406↩

07ASTANA1147↩

06ASTANA88, 07ASTANA367, 06ASTANA368, 07ASTANA613↩

06ASTANA368↩

07ASTANA1061↩

07ASTANA1147↩

Napper Interview↩

05ALMATY1938, see also Christopher Smith, U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, “Kazakhstan’s Candidacy for OSCE Chairmanship,” 109th Cong., 2nd sess., 2006, http://www.csce.gov/index.cfm?FuseAction=ContentRecords.ViewDetail&ContentRecord_id=302&ContentType=S&ContentRecordType=S&Region_id=0&Issue_id=0&IsTextOnly=True↩

08ASTANA1355↩

07ASTANA1666↩

05ALMATY406↩

07ASTANA1666↩

07ASTANA2113↩

07ASTANA1925↩

09ASTANA222↩

Curiously, the US DOL Child Labor report continues to cite the problem with child exploitation in the cotton fields, while the human trafficking reports does not.↩

09ASTANA210, 09ASTANA434↩

05ALMATY3419↩

08ASTANA2165. The trip was handled via the IOM, but funded by the US.↩

The International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) is the U.S. Department of State’s premier professional exchange program. 09ASTANA1042↩

05ALMATY3431↩