Japan

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/japan/.

PDFContents

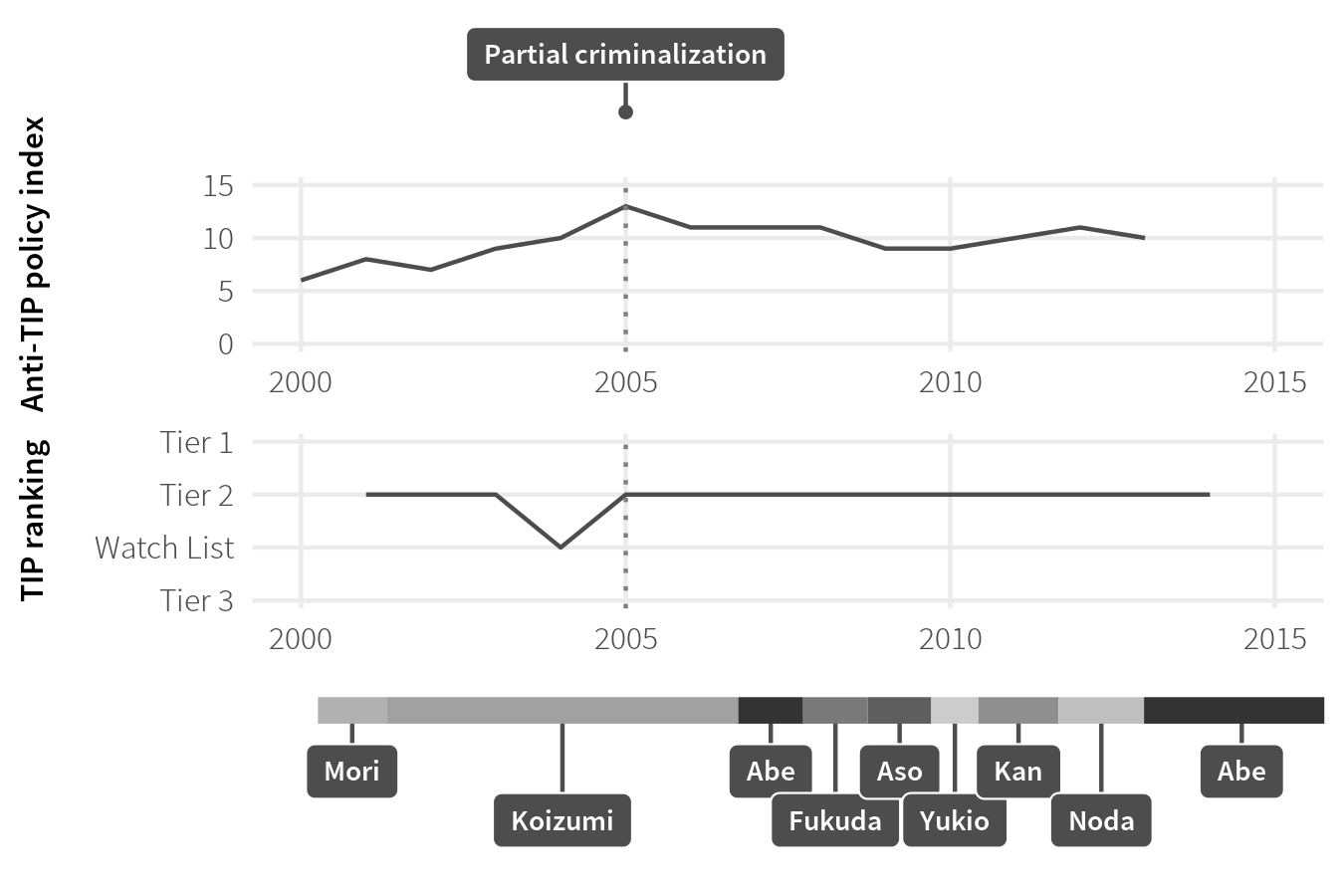

Japan illustrates the power of scorecard diplomacy, but also its weakness if the ratings become too timid. Japan was first placed on the TIP Report in 2001 as a Tier 2 country. It stayed there until 2004 when for the first time the new watch list designation was used in the report. That year Japan was the only developed nation to be placed on the US Watch List, a point not lost on the media.1 This was followed in 2005 by a similarly critical ILO report, Human Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation in Japan, highlighting Japan as a destination country with most of the victims ending up in Japan’s sex and entertainment industry.2 Japan initially associated great shame with its placement on the Tier 2 watch list in 2004, comparing itself with other countries and asking how to improve. The ranking motivated the government to demonstrate increased efforts to fight TIP, but when they failed to reach Tier 1 as hoped, the government became frustrated. The State Department’s refusal to upgrade Japan caused tensions and eventually Japan resigned itself to a Tier 2 rating, satisfied that the US would not dare go further and that Japan could live with the Tier 2 rating. Little progress has occurred since the early years.

The case of Japan shows that the US can influence even in a rich peer-country, but that such relationships are also vulnerable to political pressures to consider other factors in the relations that make it hard to criticize peers. The case demonstrates the clear concern of reputation leading to policy changes, and, conversely, lack of pressure leading to lack of concern and lack of policy changes.

Background

The US has long criticized the Japanese government for its Industrial Trainee and Technical Internship Program (TITP), which recruits migrant workers, mainly from Asia. Participants pay up to $10,000 to gain entry to the program, but then face poor working conditions and contracts that bar them from leaving. The US assesses that many are subjected to forced labor. Japan is also a destination, source, and transit country for men, women and children subjected to sex trafficking. Traffickers used fake marriages to bring in women to the sex industry using debt bondage. As Figure 8 illustrates, action in Japan has generally been flat, with only the brief exception around the Watch List rating.

Figure 8: Japan’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2000–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $42,333.27 |

| Total aid | $0.12 million |

| Aid from US | $0 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 0% |

| Total TIP grants | $821,300 |

Table 8: Key Japanese statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

Scorecard diplomacy meetings to discuss TIP appeared to be infrequent with the exception of a very intense period in 2004-2005. Contacts also were often at the level of deputy or vice-positions such as officials of the National Police Agency and the Justice Ministry. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2006, although Japan was included in the report already in 2001. The cables that discuss TIP constitute just 1 percent of the overall available cables, suggesting that TIP has been a lower priority issue. Furthermore, in later years the US has been reluctant to really use the tier rankings to pressure the government. Scorecard diplomacy in the early years focused on Japan’s entertainer visa and passage of anti-TIP legislation. The relationship has been very defensive on the part of Japanese officials and it appears that the local embassy and regional offices were less keen than TIP office to pressure Japan on TIP issues, especially after the mid-2000s, when the embassy began to advocate for a more positive approach. As a result, the embassy has not been very involved with implementation issues either.

Indirect pressure

After the downgrade in 2004, the government began to involve domestic NGO representatives in the drafting of an action plan.3 Furthermore, the US sought to broaden the reach of the report by engaging with NGOs and IGOs. Shortly after the release of the report, the embassy held a symposium jointly with an NGO called Vital Voices and the ILO, which officials of the National Police Agency and the Justice Ministry attended.4 After the pressure on Japan let up, the government’s relationship with NGOs has been mixed.5 One US funded NGO shared its inability to engage the government. 6

Concerns

The evidence suggests that in 2004 and 2005 Japan worried about the drop in the Tier rating. Although the rating was not particularly low, it stigmatized Japan, because while during 2001-2003 Japan was still in the company of other developed democracies such as Canada, Israel, France and Sweden, the downgrade in 2004 left Japan as the only developed nation other than Greece to be placed on the US Watch List, which some accounts called a “global humiliation.”7 By all accounts, the government was taken aback. Japan Times noted that the government was “Still smarting from a sharp rebuke by the U.S”8 and that “The U.S. report shocked Japan.9 Nobuki Fujimoto of the Asia-Pacific Human Rights Center in Osaka also thought that “The Japanese government was very shocked to know that they were placed on that list.”10 In 2005 a newspaper headline noted, “Trafficking blots nation’s repute,” and linked the ILO report with the earlier US rating.11

Even as Japan’s Tier 2 rating was restored, the vice foreign minister said he considered it ‘embarrassing,’12 and the Organized Crime Division director said that Japan was very disappointed given how hard they’d worked.13 After the 2008 Report’s Tier 2 rating the deputy vice minister called the embassy to say that Japan was “very unhappy with this result,”14 stressing that it was “a very disappointing result, very regrettable.”15

Japanese officials often compared Japan’s status to that of other countries. Once the vice foreign minister complained that there were countries “like Colombia and Malawi receiving Tier 1 ratings.”16 On another occasion, an official pointed out that the report criticized a G-8 country for suspending sentences in all but 31% of its trafficking convictions, but that it was still ranked at Tier 1.17 In advance of the 2008 report launch, the vice foreign minister said he hoped is that Japan would no longer be a Tier II country “like Rwanda” but would be elevated to the same status as other countries such as Canada and South Korea.18 Later, the deputy vice minister complained that many other countries – such as Canada and South Korea – were ranked Tier 1, despite not cooperating as closely as Japan, which had “made progress in all areas that the United States has identified.”19 After the 2008 report, high-level officials complained to the embassy that Japan had been held to a higher standard than a number of countries that had been ranked in Tier 1. 20

One alternative possibility is that it was not Japan’s relatively low status on the Tier ratings per say that prompted action, but instead the relationship with the US in the global context. At this time Japan was keen to elevate its international status, for “political acceptance commensurate with its growing economic power ha[d] become important to Japanese foreign policy.”21 Japan was seeking to normalize its military status and had agreed to participate in the US led war in Iraq by deploying Self Defense Forces. At the same time, Japan was pushing for a seat on the UN Security Council.22 The US had agreed to support this effort in return for Japan’s contribution to the Iraq War.23 So perhaps Japan was worried that the downgrade would jeopardize US support for its efforts to raise its international standing. Even this explanation, however, comes back to Japan’s concern for its international status and fear that the Tier rating would harm this status.

Furthermore, it’s not like Japan did not take its relationship with the US seriously before 2004. It was clear, at least to US TIP Ambassador Miller, that the drop to the watch list was essential to motivate action on TIP, which is why he pushed so hard for it, against the other pressures in the Department of State to leave Japan on Tier 2. Indeed, the goodwill towards Japan was so high in the DOS that Miller had to go to extraordinary lengths to obtain the ambassador to Japan’s support for the drop in the rating.24 After the government began to implement policy changes, it was keen to communicate these not only to the US, but to others as well, hence the issuance of the English language brochure, discussed below.25

Outcomes

Legislation

Japan responded swiftly to its downgrade to the Watch List. By December 2004, the Inter-Ministerial Liaison Committee and the Anti-Trafficking Task Force produced the National Action Plan of Measures to Combat Trafficking in Persons. Out of this came revisions to Japan’s Penal Code, the Law on the Control and Improvement of Amusement and Business, and the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act, all in 2005.26 Another big change that year was the tightening of the criteria for the eligibility for Japan’s entertainer visa, which the US had said was being misused for TIP. Demonstrating Japan’s desire to improve its reputation on this front, the MOFA produced a glossy brochure detailing all these actions in English.27 The Director of MOFA’s International Organized Crime Division said that he had “never seen the Japanese government undertake such a concerted effort across so many different bureaucracies and agencies.”28 Commentators attributed Japan’s new impetus to acknowledge the TIP problem to American pressure.29 “The NGOs are becoming more vocal,” said Andrea Bertone, director of HumanTrafficking.org, a clearinghouse for trafficking-related issues. “But the primary motivation for the Japanese government is the U.S. pressure.”30

Although the US pressure had prompted results in 2005, after that the US and Japan entered a long period of contention about the adequacy of Japanese laws. Japan continued to make some efforts,31 but grew frustrated with continued US criticism, lambasted it as subjective and inaccurate, and accused the US of moving the goalposts. Japan’s government was very frustrated and expressed that Japan deserved a Tier 1 rating and even threatened to stop cooperating on the issue if the US would not be more forthcoming about the criteria. Demonstrating that it cared about the rating still, the government asked very specifically what it should do to obtain Tier 1.32 During 2007, the government therefore sought and the US provided a “Roadmap to Tier 1”. However, progress stagnated and over the years, the lingering Tier 2 rating became an irritant in the relationship and Japanese officials eventually started threatening to withdraw all cooperation on TIP.33 Relations continued to deteriorate as the US DOS, over the objections of the US embassy in Japan,34 continued to rate Japan a Tier 2 and eventually resumed its criticism of lack of a comprehensive TIP law. When Japan was once again Tier 2 in 2008, the Deputy Vice called the embassy to say that he was “very unhappy with this result,” asserting that Japan had made progress in all areas that the United States had identified, and has merited a Tier 1 ranking.35 The relationship got so bad that later in 2009 after the US made a proposal for a policy change, Deputy Director Hiroki Matsui of MOFA’s International Organized Crime Division warned that it would be better for this not to be seen as coming from the US, because there was now so much resistance to US input.36

Institutions

In April 2004 the Government established an Inter-Ministerial Liaison Committee (Task Force) on TIP,37 but it’s not clear this was due to US pressure. Other evidence of US-inspired institutions was not found.

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

Before the US pressure, Japan had been skeptical of trafficking as a problem.38 The US scorecard diplomacy helped to change these attitudes. Advocates for trafficking victims attribute Japan’s new impetus to acknowledge the TIP problem to American pressure.39 However, the US has not been able to persuade the government that its internship program exposes participants to human trafficking-like conditions.

Conditioning factors

Whatever progress the US accomplished in Japan was due to the initial willingness of the TIP Report to criticize Japan and the huge reputational concerns on Japan’s part with its international image. However, the fact that the government officially sponsored an internship program that the US considered exploitative and borderline trafficking — so much so that the TIP Report one year featured photos of recruits in its annual report— was a point of continuous tension between the governments. Relatedly, disagreements about what constituted TIP led to official renunciation of the US definition of problem and therefore of US criticism. In addition, internal US disagreements about the priority of the problem between the embassy and the State Department TIP office complicated efforts to pressure Japan. Although Japan’s hospitality industry and its government-sponsored international internship program contribute to human trafficking, after 2005 political constraints have prevented the TIP office from criticizing and rating Japan sufficiently low to garner effective action. This has been the biggest obstacle to change.

References

Katzenstein, Peter J. 1996. Cultural norms and national security: Police and military in postwar Japan. Cambridge Univ Press.

Onishi, Norimitsu. 2005. “Japan, easygoing till now, plans sex traffic crackdown.” In New York Times. New York.

Paul Capobianco, “Human Trafficking in Japan: Legislative Policy, Implications for Migration, and Cultural Relativism,” (MA diss., Seton Hall University, 2013), http://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2891&context=dissertations.↩

http://www.ilo.org/sapfl/Informationresources/ILOPublications/WCMS\_143044/lang--en/index.htm↩

Nao Shimoyachi, “Government’s Human Trafficking Plan ‘Inadequate,” Japan Times, 15 October 2004, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2004/10/15/national/governments-human-trafficking-plan-inadequate/\#.VjyopoSE7ww.↩

Govt must act on human trafficking, The Daily Yomiuri (Tokyo), 25 June 2004, p. 4.↩

07TOKYO1028↩

Email exchange with Aiki, Lighthouse: Center for Human Trafficking Victims, July 15, 2014↩

Paul Capobianco, “Human Trafficking in Japan: Legislative Policy, Implications for Migration, and Cultural Relativism,” (MA diss., Seton Hall University, 2013), http://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2891&context=dissertations, p. 13↩

“Legal Changes Eyed to Combat Trafficking of Human Beings,” The Japan Times, 4 Jul. 2004, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2004/07/04/national/legal-changes-eyed-to-combat-trafficking-of-human-beings/\#.VjzdG4T93ms.↩

Eric Johnston, “Human Trafficking Woes Fail to Gain Recognition,” The Japan Times, 23 Sep. 2004, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/2004/09/23/announcements/human-trafficking-woes-fail-to-gain-recognition/#.VjzdxoT93ms.↩

Steve Silver, “The Trafficking Scourge: Japan Has Tackled Sex Trafficking, But Challenges Remain,” The Japan Times, 15 Aug. 2016, accessed 26 Dec.2016, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2006/08/15/issues/the-trafficking-scourge/\#.VjzeYIT93ms.↩

Trafficking blots nation’s repute, The Daily Yomiuri (Tokyo), November 23, 2004, page 4.↩

07TOKYO2481↩

07TOKYO2788↩

08TOKYO1350↩

08TOKYO1528↩

07TOKYO2481↩

07TOKYO3186↩

08TOKYO1263↩

08TOKYO1350↩

08TOKYO2577↩

Katzenstein 1996 42.↩

“Japan Pushes for U.N. Security Council Seat,” CNN.com, 22 September 2004. http://edition.cnn.com/2004/US/09/22/un.reforms/index.html↩

Ian Williams, “Security Council Reform Debate Highlights Challenges Facing UN,” Foreign Policy in Focus, 10 August 2005. http://www.fpif.org/fpiftxt/230↩

Personal interview, John Miller. June 16, 2014. Phone.↩

“Japan’s Actions to Combat Trafficking in Persons, A Prompt and Appropriate Response from a Humanitarian Perspective,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan, 2004, http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/i\_crime/people/pamphlet.pdf.↩

09TOKYO1185. For a fuller discussion of the legislative changes, see also: Capobianco, “Human Trafficking in Japan,” http://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2891&context=dissertations, p. 28.↩

“Japan’s Actions to Combat Trafficking in Persons, A Prompt and Appropriate Response from a Humanitarian Perspective,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan, 2004, http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/i\_crime/people/pamphlet.pdf↩

09TOKYO1185_a↩

Onishi, Norimitsu. 2005. Japan, easygoing till now, plans sex traffic crackdown. New York Times, Section A, Column 1, Foreign Desk, p.1, February 16.↩

Steve Silver, “The Trafficking Scourge: Japan Has Tackled Sex Trafficking, But Challenges Remain,” The Japan Times, 15 Aug. 2016, accessed 26 Dec.2016, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2006/08/15/issues/the-trafficking-scourge/\#.VjzeYIT93ms.↩

“The Recent Actions Japan Has Taken to Combat TIP (Trafficking in Persons),” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, March 2008, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/i_crime/people/action0508.html.↩

07TOKYO3186↩

09TOKYO1185↩

09TOKYO1162↩

08TOKYO1350↩

09TOKYO2328↩

“Japan’s Action Plan of Measures to Combat Trafficking in Persons,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, December 2004, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/i_crime/people/action.html.↩

Onishi, Norimitsu. 2005. Japan, easygoing till now, plans sex traffic crackdown. New York Times, Section A, Column 1, Foreign Desk, p.1, February 16.↩

Onishi 2005.↩