Israel

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/israel/.

PDFContents

This case illustrates many of the key mechanisms of scorecard diplomacy. The US TIP Report ratcheted government attention to human trafficking in Israel. Once the report shone the spotlight on Israel, the government convened committees and seminars to examine the issue. The attention led to policy changes, including the passage of comprehensive anti-trafficking legislation, adopting a national action plan, and stepping up practical ways to fight trafficking. As part of the pressure for new legislation, the US shaped how trafficking was defined, effectively broadening the law to include labor trafficking. The US also influenced domestic institutions by promoting and funding domestic shelters, prompting the government to create new committees that directly examined the annual TIP Report, and even influencing the choice of the official anti-TIP coordinator, a person to whom the US named as TIP Hero, thereby increasing her profile.

Foremost, Israel illustrates how countries can become very concerned with their reputation, not simply driven by economic concerns, but by concerns about image and status. Israeli officials were ashamed that Israel was grouped with less socially desirable states and referred directly to Israel’s international reputation. They expressed desire to obtain a better rating, even when sanctions were not looming. The case also illustrates how scorecard diplomacy empowers other actors. Israeli NGOs and others used the report as an opportunity to criticize the government.

Background

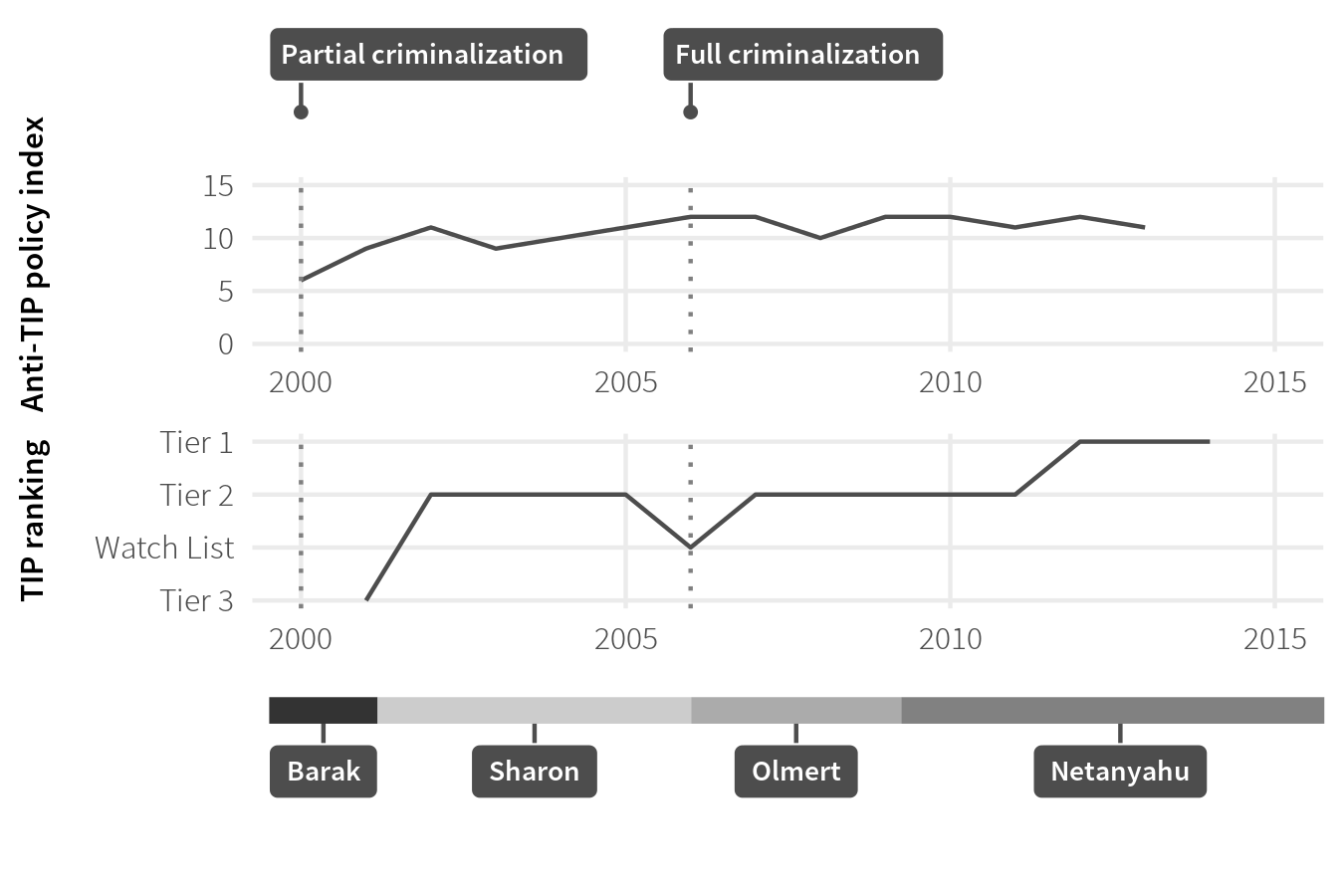

Israel is primarily a destination country for men and women subjected to forced labor and sex trafficking. Low-skilled workers arrive for temporary low-skilled manual labor jobs from Asia, Eastern Europe, and West Africa. Women from Eastern Europe, Uzbekistan, China, Ghana, and other places enter on tourist visas to work in prostitution, but become victims of trafficking. Pressures to combat TIP were present already in the late 1990s as the international attention to human trafficking was increasing, but despite high profile criticism from organizations like Amnesty International inaction persisted. A Knesset’s commission of inquiry held only two sessions before its six-month mandate expired. NGOs criticized the lack of government’s response.1 Israel was initially very surprised by the harsh US Tier 3 rating. Since then, Israel has made policy progress, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Israel’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2000–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $28,928.66 |

| Total aid | $3,520.40 million |

| Aid from US | $3,294.01 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 0.34% |

| Total TIP grants | $1,624,909 |

Table 7: Key Israeli statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

Scorecard diplomacy meetings to discuss TIP were frequent and often at the highest levels such as ministers and heads of state. Over the years, these included the defense minister, foreign minister, a National Police (INP) Colonel, the justice minister, the minister of industry, trade, and labor, as well as party leaders. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2004, although Israel was included in the report already in 2001. The cables that discuss TIP constitute just 2 percent of the overall available cables, but this likely reflects the overall strong relationship with Israel and the many other top priorities, not that TIP was not a salient issue. In the beginning scorecard diplomacy both directly from the Department of State and from the embassy was focused on bringing attention to the issue and getting the government to admit to the problem. Later on the focus was on shaping how trafficking was defined so that it included labor trafficking. Scorecard diplomacy was very hands on. Downgrades were used to push for action, and the ambassador set conditions for an upgrade in a series of intensive meetings on TIP. The US also promoted and funded domestic shelters and advocated for the choice of the official anti-TIP coordinator, and encouraged the government to create a national action plan.

Indirect pressure

NGOs and the media magnified the pressure of scorecard diplomacy in Israel. Throughout the years, the report received extensive media coverage,2 with the embassy holding digital videoconferences and using funding to keep the issue in the media.3 NGOs referenced the report to address the government. For example, in 2001, Kav LaOved of the NGO Workers’ Hot Line issued a statement saying, “We hope that this report will cause the Israeli authorities to understand the seriousness of the problem and begin to treat the phenomenon with the seriousness it deserves”4 Furthermore, in 2006, the impending release of the TIP Report mobilized Jews worldwide. Over 3,000 signed a petition calling for the GOI to stamp out the practice of human trafficking, to be brought before the prime minister to coincide with the release of the TIP Report.5 NGOs also served as sources of information for the report.6

Concerns

When the first US TIP Report came out in 2001, Israel was one of 23 countries given the harshest rating, a Tier 3, in the report. This shocked many in Israel, as the rating garnered considerable coverage in The Jerusalem Post. Israeli officials were foremost driven by concern about Israel’s international image. Although the immediate response to the initial 2001 Tier 3 was for the government to call an “Urgent meeting due to concern about economic sanctions following the publication of the U.S. State department report, that includes Israel in a ‘blacklist’ of countries that traffic in persons,”7 it was the shame of blacklisting rather than fear of the economic effects of aid sanctions that motivated Israeli officials, a fact supported by one-on-one interviews.8 Sanctions, if anything, were more stigmatizing than financially consequential. Indeed, in 2001, any threat of sanctions was still two years away due to the rules of the US legislation at the time, and the US president would have to make a special determination on the matter, providing yet another safeguard against sanctions coming into play. Similarly, once Israel moved to Tier 2, concerns did not abate just because the threat of sanctions was removed. 9 Efforts were explicitly designed to move Israel to Tier 1. Officials wanted Israel to be seen as a top performer, a sentiment also often expressed in private meetings. All in all, the threat of sanctions or even Israel’s special relationship with the US likely mattered, but was at best part of the story.10 Rather, in numerous interviews, Israeli officials said they feared the report undermined Israel’s quest for international legitimacy and “clashed with its self-identity.”11 Officials saw TIP as important to Israel’s “society and values,” as Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni told the US attorney general.12 In 2001, the Head of the Foreign Ministry’s Human Rights department said that the international repercussions of the report for Israel are “severe and steps must be taken to remove Israel from the unflattering category [emphasis added].”13 Officials noted the importance of Israel being part of global norms in connection with the passage of the 2006 law, which Law and Justice Committee Chairman Menachem Ben-Sasson (Kadima) said placed “Israel in line with the world’s most enlightened nations [emphasis added].”14 Comparisons were important. As Deputy Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon said in 2009 to the Knesset subcommittee analyzing the TIP Report, Israel did not want to be “lumped” with pariah states, worrying about the “troubling political implications” of receiving the same Tier Ranking as “states like Afghanistan, Jordan, and Botswana.”15

Outcomes

US efforts were key in boosting attention to TIP. Pressures to combat TIP were present already in the late 1990s, but despite criticism from organizations like Amnesty International, inaction persisted. A Knesset’s commission of inquiry held only two sessions before its six-month mandate expired. NGOs criticized the government’s lack of response.16 After the TIP Report rated Israel a Tier 3 in 2001, the internal security minister held an emergency conference “on setting the matter as a top police priority.”17 The government quickly got to work on how to improve the rating.18 The Knesset summoned the committee of inquiry into the trafficking of women. Also immediately following the report, the minister of public security initiated a seminar on trafficking that included participants from numerous ministries, law enforcement, NGOs and the Knesset. Many sources attribute the changes in attention to the US report.19

Policy changes also followed. The Attorney-General Elyalkim Rubinstein called for a crackdown on trafficking in women, charging that law enforcement officials were not doing their job.20 In 2003, the GOI established the Border Police Ramon Unit to patrol along the Egypt-Israel border, and Israel passed the Criminal Organizations Bill, which facilitated the prosecution and punishment of key members of several organized TIP operations.21 In January 2004 in Belarus, the Israel Police conducted the first-ever joint investigation with a foreign police force on trafficking of women.”22 Following US pressure, in February 2004 the government opened the first shelter for trafficking victims using U.S. funds.23

Legislation

The US also played a strong role in changing legislation. Frequent elections interfered with progress on TIP, so in 2006 the TIP Report downgraded Israel to the watch list. This upset GOI officials, some of whom claimed Israel had made significant effort, but the US ambassador cited legislation against labor trafficking as a sine qua non for an upgrade.24 Direct engagement followed with high-level officials like Foreign Minister Livni, Justice Minister Ramon, and Defense Minister Peretz, who also headed the Labor Party.25 Progress was not easy; Livni explained that political “turmoil” impeded attention to TIP.26 Nonetheless, the US pushed repeatedly for attention to TIP, particularly the legislation against labor trafficking,27 linking Israel’s demotion to the watch list to lack of effort on labor trafficking.28

June 2006 was packed with meetings on the legislation with the minister of industry, trade, and labor and Shas Party Chairman Eliyahu Yishai and others.29 The ambassador also spoke with Knesset Speaker Dalia Itzik who promised to take up TIP funding in the new budget.30 US Attorney General Alberto Gonzales met the Israeli Minister of Justice Haim Ramon and expressed concern that Israel was “trending in the wrong direction” in its handling of trafficking issues, specifically citing the lack of legislation to outlaw labor trafficking. He also made the same point directly with Prime Minister Olmert and was assured that the bill would progress soon.31 July and August were equally intensive with meetings. The ambassador continued discussions with Itzik, who kept the ambassador abreast of Knesset anti-trafficking actions, including two new laws to strengthen enforcement and provide legal aid to trafficking victims.32 In the fall, the ambassador met with Acting Minister of Justice Meir Sheetrit and “stressed the importance of including assistance for legal support for victims of labor trafficking in new legislation now before the Knesset.”33 To gain support across the political spectrum, the US ambassador also met with Likud leader Netanyahu, who pledged to support the legislation.34 In October 2006 the new trafficking law passed, adding labor trafficking to the definition of trafficking.35 In December 2007 Israel also followed up on recommendation to create a national plan as recommended in the TIP Report.

All in all, Israel has made significant progress since 2001, and since 2012 has maintained Tier 1 status, which Israeli politicians have pointed out in the media.36

Institution building

US efforts influenced some Israeli institutions. Following US pressure, 37 in February 2004 the government opened the first shelter for trafficking victims using U.S. funds.38 The Knesset subcommittee on women has also repeatedly held meetings to review the US TIP Report, suggesting the report became part of the regular policy discussions.39 In these meetings, the report has led to discussion of substantial issues. In one meeting the chairperson noted that “the TIP Report raises the need for some new thinking by the GOI [emphasis added]. We will have to give thought to the question of incriminating clients of the sex industry and the issue of sex service advertising and we will be doing that in the next parliamentary session.”40 The US also attended committee meetings in Knesset to discuss TIP.41 Finally, US efforts also played a role in the appointment of TIP officials. Awarding Rachel Gershuni, a prominent NGO leader, as a TIP Hero helped her to be heard by the government42 and eventually appointed as anti-TIP coordinator in the Ministry of Justice.

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

As per the discussion of legislation, scorecard diplomacy played a role in defining labor trafficking as part of human trafficking in a country that had until then, heavily focused on sex trafficking. Scorecard diplomacy also increased the focus on victims and the provision of services. In 2008, an official from the State Attorney’s Office also took issue with the TIP Report’s mention of internal trafficking and Israel as a source country for trafficked women, noting that… “We do not recognize the phenomenon of internal trafficking as referred to in the report.” 43 Over the years, the TIP report did a lot to change attitudes towards human trafficking in Israel and normalize the discussion in Israeli politics of trafficking problems.

Conditioning factors

Several factors hampered scorecard diplomacy in Israel. Initially officials were unwilling to acknowledge the problem at all. Later, frequent elections hampered the legislative progress. In 2006 Foreign Minister Livni explained that “turmoil within the GOI over the last several years—when elections on average took place every two years—made it difficult for the GOI and the Knesset to maintain a sustained focus on the labor trafficking issue and legislation addressing it.”44

On the other hand, other factors facilitated influence. One of these was the special relationship and the very close diplomatic contact that the countries have enjoyed since the end of WWII. This gives the embassy particularly high- level access to officials. The large aid relationship may also be helpful, although it’s difficult to believe that Israel truly thought that aid could be suspended over the TIP issue. The embassy also benefitted from an active civil society and media and a strong official concern for the country’s international image.

References

Alon, Gideon. 2002. “Report: 3,000 Women a Year Trapped in Sex Slave Industry.” In: Haaretz.

———. 2006. “Human Traffickers to be Sentenced to 16-20 Years in Prison.” October 17, 2006. <http://www.haaretz.com/news/human-traffickers-to-be- sentenced-to-16-20-years-in-prison-1.201598> (January 5, 2016).

Efrat, Asif. 2012. Governing Guns, Preventing Plunder: International Cooperation against Illicit Trade. Oxford.

Gilbert, Nina. 2001. “Coalition MKs losing restraint.” In Jerusalem Post.

The Jerusalem Report, “VICTORIA’S, AND ISRAEL’S, UGLY SECRET”, March 12, 2001, http://www.lexisnexis.com/hottopics/lnacademic/, http://solargeneral.com/jeffs-archive/slavery/victorias-and-israels-ugly-secret/↩

TELAVIV669; 06TELAVIV2072; 06TELAVIV2157; 06TELAVIV2239; 07TELAVIV1727; 07TELAVIV3314; 08TELAVIV1185;09TELAVIV1564↩

07TELAVIV930↩

The Jerusalem Post, “US: Israel Among States Lax on Human Trafficking”, July 13, 2001, LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed July 27, 2012.↩

06TELAVIV2072↩

05TELAVIV1679↩

Protocol no. 14 of the Parliamentary Inquiry committee, cited in Efrat 2012 204.↩

Interviews with Galon, Gershuni and Schonmann by Asif Efrat and cited in Efrat 2012.↩

Alon 2002.↩

As reported in local media. See 05TELAVIV669↩

See Asif Efrat’s chapter in his book, Governing Guns, Preventing Plunder, which is based on numerous interviews done by Efrat and shared with the author. Efrat 2012 206.↩

06TELAVIV2618.↩

Gilbert 2001.↩

Alon 2006.↩

09TELAVIV1564↩

The Jerusalem Report, “VICTORIA’S, AND ISRAEL’S, UGLY SECRET”, March 12, 2001, LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2012/07/27.↩

The Jerusalem Post, “Coalition MKs Losing Restraint”, July 19, 2001, LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2012/07/27.↩

The Jerusalem Post, “US: Israel Among States Lax on Human Trafficking”, July 13, 2001, LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2012/07/27.↩

“Israel’s Thriving Sex Industry Records One Billion Dollars a Year”, December 9th, 2002., http://www.albawaba.com/business/israel%E2%80%99s-thriving-sex-industry-records-one-billion-dollars-year-0. See also “US report shows Israel clamping down on trafficking in women,” Lexis Nexis. Jerusalem Post, 6 June 2002, and Vered Lee, “Human Trafficking to Israel Has Been Beaten. Let’s Now Tackle Prostitution,” Haaretz, 17 Mar. 2014, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/opinion/.premium-1.580160↩

A-G calls for crackdown on trafficking in women, Jerusalem Post, http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P1-46020247.html, August 1, 2001. Marion Marrache↩

05TELAVIV1679_a, 05TELAVIV1336_a.↩

05TELAVIV1337_a↩

07TELAVIV1672; Gideon Alon and Ha’aretz Correspondent, “3,000 Women A Year Trapped In Israel’s Sex Slave Industry”, Haaretz, 8 Dec. 2002, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/report-3-000-women-a-year-trapped-in-sex-slave-industry-1.26034; 07TELAVIV599↩

06TELAVIV2226↩

06TELAVIV1932, also 06TELAVIV1984.↩

06TELAVIV2618↩

06TELAVIV1923; 06TELAVIV1945; 06TELAVIV1980; 06TELAVIV2413; 06TELAVIV2784; 06TELAVIV3785; 06TELAVIV3843↩

06TELAVIV2620; 06TELAVIV2621↩

06TELAVIV2413.↩

07TELAVIV2413↩

06TELAVIV2620↩

06TELAVIV2784, 06TELAVIV3482↩

06TELAVIV3785↩

06TELAVIV3843↩

05TELAVIV1336; 05TELAVIV133706TELAVIV914; 06TELAVIV915; 06TELAVIV1923; 06TELAVIV2621; 06TELAVIV3482↩

Vered Lee, “Human Trafficking to Israel Has Been Beaten. Let’s Now Tackle Prostitution,” Haaretz, 17 Mar. 2014, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/opinion/.premium-1.580160, and Greer Fay Cashman, “Israel Leading World in Prevention and Reduction of Human Trafficking,” The Jerusalem Post, 2 Dec. 2014, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Politics-And-Diplomacy/Israel-leading-world-in-prevention-and-reduction-of-human-trafficking-383473.↩

“Justice Minister Friedmann on Refugees, Ipr And”, n.d., http://dazzlepod.com/cable/07TELAVIV1672/?q=israel%20trafficking.↩

“3,000 Women A Year Trapped In Israel’s Sex Slave Industry”, n.d., 0, http://rense.com/general32/trapped.htm, and “GOVERNMENT OF ISRAEL ANNOUNCES NATIONAL PLAN TO”, n.d., http://dazzlepod.com/cable/07TELAVIV599/?q=tip%2C%20embassy%20Tel%20Aviv.↩

08TELAVIV1578↩

08TELAVIV1578↩

07TELAVIV3314↩

06TELAVIV1652↩

08TELAVIV1578_a, 08TELAVIV1185↩

06TELAVIV2618↩