Indonesia

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/indonesia/.

PDFContents

The US embassy worked closely with a broad set of actors such as the police, key ministries, NGOs, and the legislature. The relationship with the police was particularly intense and successful. Considerable influence came from training Indonesian law enforcement and judiciary. The US also played a particularly notable role in pushing along comprehensive Indonesian anti-TIP legislation. The US often brought up progress on the legislation as an incentive for tier improvement and, after passage, continued to tie the tier rating to implementation issues.1 Several of the mechanisms of scorecard diplomacy were in view in Indonesia. The embassy worked very closely with the NGO community, with local police, and with officials in the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection as well as the Ministry of Manpower, especially the Ministry of Manpower Secretary General, I Gusti Made Arka, who was an effective interlocutor.

Indonesia illustrates the importance of how scorecard diplomacy can be used to engage third party actors, often letting them take the lead on the fight against TIP. Indonesia was keen to take actions that the US made pre-requisites for improving the US TIP Tier ranking.

Background

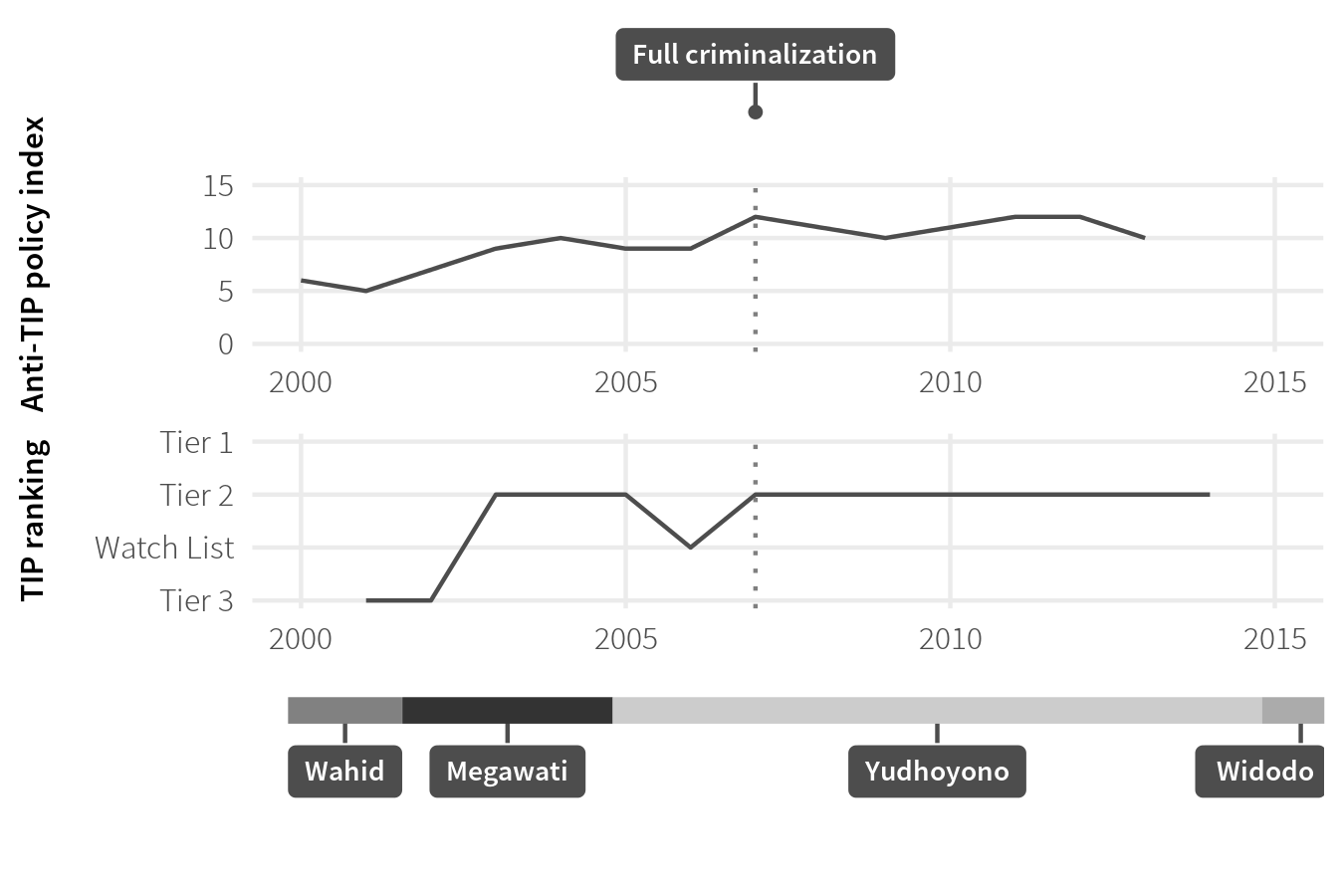

Indonesia is a major source country with millions of Indonesians working abroad, especially in Malaysia, in domestic service, construction, factories, or on plantations or fishing vessels where many experience forced labor through debt bondage. To a much lessor extent, Indonesia is also a destination and transit country for women, children, and men subjected to sex trafficking and forced labor. The country was at high risk for human trafficking, especially as the countries surrounding it in Southeast Asia also had significant trafficking problems. As Figure 6 shows, The TIP rating started out at the worst level 3, but has stabilized at Tier 2 since 2005 in light of several policy improvements.

Figure 6: Indonesia’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2000–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $2,798.78 |

| Total aid | $82,466.90 million |

| Aid from US | $4,459.55 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 0.999% |

| Total TIP grants | $35,201,686 |

Table 6: Key Indonesian statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

Scorecard diplomacy meetings to discuss TIP were typically at an intermediate level such as directors. These included the Manpower Ministry’s Secretary General and officials from the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2006, although Indonesia was included in the report already in 2001. Perhaps because of this, the cables that discuss TIP constitute just 5 percent of the overall available cables, although it appears that TIP was a priority for the embassy, which sought to cultivate strong relationships. The US pushed for comprehensive Indonesian anti-TIP legislation and often brought up progress on the legislation as an incentive for tier improvement. The government was keen to take actions before the US TIP reporting deadline. The US also a funded a technical advisor to work with the parliamentary committee on the legislation and the embassy submitted comments on the language throughout the process, focusing on an expanded definition of human trafficking. Scorecard diplomacy also tied the tier rating to implementation issues and worked with closely with police and funded public awareness campaigns. The embassy was quite hands-on and traveled to the field to assess implementation needs. As reflected in the large share of TIP grants to Indonesia, scorecard diplomacy was also heavily involved with capacity building, including establishment of medical centers, and shelters.

Indirect pressure

The embassy worked very closely with NGOs,2 who served as a source of information for the report and as partners in many efforts.3 On the push for passage of comprehensive anti-TIP legislation, the embassy noted, “The bill’s passage represents the culmination of over two years’ worth of intense anti-trafficking collaboration between Post, its NGO partners, and the [government of Indonesia].”4 Several IGOs were also active, including the IOM, the ILO, and UNICEF. The US worked very closely with the IOM,5 and together with the ILO held workshops to educate government officials about human trafficking, thus clearly boosting attention to the issue.6 The US DOL also funded multi-year multi-million dollar ILO programs to combat child labor.7

The interconnectedness of US funding and work of IGOs and NGOs is well illustrated by a comment made in the embassy about a local NGO: “This local NGO, which specialized in helping the victims of trafficking, is itself supported by IOM, which is funded in part by the United States.8

Indeed, the US preferred to work through NGOs and IGOs. The was evident, for example, when the US hosted a TIP-focused meeting with donors and NGOs to discuss US recommendations for international projects and how donors can exert more influence on TIP in Indonesia and jointly lobby the government with local NGOs and the US. The over 40 people attending the 3-hour meeting established joint priorities and methods for information exchange. Key actors included UNICEF, the IOM, and the US-based and heavily US-government funded NGO Save the Children. Interestingly, the US saw the benefit of collaboration as being one where the US was not always in the lead; one objective was to establish more powerful multilateral efforts and “take the USG out of the position of being the only strong voice calling for stronger political action.” The effort was meant as a way to amplify US pressure: “We hope to leverage this new grouping into our effort to further improve Indonesia’s Tier Two standing after it was removed from the Watch List earlier this year.”9 The wish to stay in the background while supporting NGOs was evident in embassy cables from 2008 as well.10

Concerns

Indonesia showed significant political will to fight human trafficking and government officials emphasized their concern about low Tier ratings.11 It’s clear that the Tier ratings focused attention and motivated action. That said, the cables do not reveal much about the motivations of the government’s response to the US efforts. Most reactions to the TIP Reports are cooperative and most interaction factual and practical.

Outcomes

Legislation

The US played a particularly notable role in pushing along comprehensive Indonesian anti-TIP legislation. When Indonesia first entered the report as a Tier three country in 2001, it had no TIP-specific legislation. Law enforcement was weak during this time as Indonesia was transitioning towards democracy. The US often brought up progress on the legislation as an incentive for Tier improvement. The US embassy urged heavily that Indonesia pass anti-TIP legislation, in several meetings in 2006.12 A US-funded technical advisor worked with the parliamentary committee on the legislation.13 As the legislation moved along, the US submitted comments on the language, which led to a significantly expanded definition of human trafficking.14 Even so, the US was concerned that debt bondage, a major form of human trafficking for Indonesia driven by cross-migration with Malaysia, remained unaddressed.15 The US also sought to expedite the legislative process16 and worked with Women’s Empowerment Ministry to host public hearings and to push a series of official meetings and actions. Indicative of the US’ investment in getting Indonesia to pass an anti-TIP law, in September 2006, the embassy noted to Washington, “We are pushing the GOI hard here and request Washington policymakers to push GOI visitors as well.”17 The bill finally passed on March 20, 2007, right as the embassy was due to file its TIP update to Washington.18 Although the US embassy still wished that the final legislation had clauses on forced prostitution and child exploitation,19 the final version did forbid debt bondage and the US embassy claimed to have contributed significantly to the passage and content of the law.20

The US was encouraged by the passage of the new legislation but also continued to focus on implementation and tie the Tier rating to it.21 The US poured significant funding into Indonesia, and in 2006 they were cited as the largest donor to combat child labor in the country.22 After the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment TIP law implementation task force leader told the US that the GOI lacked sufficient funding to implement every aspect of the anti-TIP legislation,23 the US worked with the Indonesian police to implement the law through DOJ-sponsored “Operation Flower” to save sexually exploited children.24 The US’ involvement was more than deskwork: embassy staff also travelled widely to see the situations for themselves.25 The embassy’s engagement with the police was particularly intense and successful.26

Institution building

The US was heavily involved with capacity building and training. It helped establish medical centers to treat TIP victims specifically,27 work that continued into 2007, leading to a fully functional hospital with psychological treatment options.28 The US also trained police, senior officials, prosecutors, and judges.29 The police training led to the creation of local anti-TIP units in big cities such as Jakarta,30 and local officials agreed extensive training had improved police dealings with TIP.31 These projects all focused on improving the skills of relevant Indonesian institutions. USAID funded a TIP shelter that worked with the police to offer victim services.32 The US also funded improvements in communications between government agencies through better technology and technical assistance. This included setting up a website for the Ministry to raise public awareness of human trafficking in Indonesia.33

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

As noted, scorecard diplomacy contributed to an expanded definition of trafficking and the criminalization of debt bondage. Furthermore, The training worked to convey a different attitude towards TIP and TIP victims. The head of the Indonesian National Police anti-TIP unit, Anton Charlyan, noted that as a result Indonesian police improved their dealings with TIP.34 In 2008, the US held a workshop on migrant protection with the ILO, which led to the Manpower Ministry’s Secretary General I Gusti Made Arka announcing that he would like to work closely with the US on the issue of migrant trafficking and exploitation, and adhere more closely to US standards. 35 Later in 2008, senior officials from the Ministry of Manpower participated in USDOG training, and following the training, requested further USG training on TIP. These groups were even considered by the US to be the least receptive to Indonesia’s relatively new anti-TIP law, and their reaction to the training was considered a success for US efforts to change attitudes towards TIP.36 The US augmented its training presence in 2009,37 and NGOs explained how they benefited from US training, and urged the Indonesian government to learn more from the United States.38

Conditioning factors

Progress in Indonesia was hindered by the corruption of law enforcement officials.39 Furthermore, the embassy and the Department of Labor (DOL) disagreed about how hard to push. In one cable, the embassy questioned the DOL about how their draft list regarding products made from Indonesian child labor was constructed, and in another it questioned the reliability of DOL reports of Indonesian child labor.40

Meanwhile, several factors facilitated US influence, foremost the government’s own considerable political will on the ministerial levels, but also the high US funding of Indonesian NGOs and official training programs, and a strong relationship with police. Scorecard diplomacy in Indonesia thus was helped by the presence of effective interlocutors in the local police, the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection, and the Ministry of Manpower, especially the Ministry of Manpower Secretary General, I Gusti Made Arka.

News: 6/28/2007, 3/1/2007: 07JAKARTA590, 2/29/2008: 08JAKARTA415, 1/20/2009: 09JAKARTA105, 2/27/2010: 10JAKARTA258↩

09SURABAYA99, 07JAKARTA2167↩

06JAKARTA2849↩

07JAKARTA778. See also Eric Green, “Nongovernmental groups key in battle against human trafficking,” IIP Digital, U.S. Department of State,14 June 2007, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/article/2007/06/200706141538591xeneerg0.9905512.html.↩

07JAKARTA1560↩

08JAKARTA191↩

08JAKARTA1345↩

07SURABAYA3489↩

07JAKARTA3238↩

08JAKARTA269↩

06JAKARTA7216, 07JAKARTA1655↩

06JAKARTA7216, 06JAKARTA10924, see also http://web.archive.org/web/20080212224531/http:/mensnewsdaily.com/2006/11/04/us-official-urges-indonesia-to-crack-down-on-human-trafficking/↩

06JAKARTA7216↩

06JAKARTA3680↩

06JAKARTA3680↩

06JAKARTA10924↩

06JAKARTA10924↩

07JAKARTA778↩

07JAKARTA3359↩

07JAKARTA778↩

BBC Monitoring Asia-Pacific; 11/5/2006, LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2012/07/27.

“US Special Envoy warns Indonesia on human trafficking”; 06JAKARTA3680; 07JAKARTA590; 08JAKARTA415; 09JAKARTA105; 10JAKARTA258↩

06JAKARTA13503↩

07JAKARTA1655↩

07JAKARTA1909↩

07JAKARTA1560↩

07JAKARTA2641, 07SURABAYA34, 07JAKARTA1909, 07JAKARTA1560, 08JAKARTA304↩

06JAKARTA2849↩

07JAKARTA701↩

07JAKARTA1560, 08JAKARTA1005, 08JAKARTA304↩

08JAKARTA415↩

07JAKARTA2641↩

07JAKARTA1909↩

06JAKARTA12498↩

07JAKARTA2641↩

08JAKARTA191↩

5/22/2008:08JAKARTA1005↩

09JAKARTA1854↩

10/23/2009:09SURABAYA99↩

07JAKARTA1560, 09JAKARTA378, 09JAKARTA378↩

09JAKARTA159, 10JAKARTA163↩