Honduras

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/honduras/.

PDFContents

Honduras illustrates the difficulty of gaining the attention of a government in a country where other problems dwarf the trafficking issue and where poverty, crime and corruption are rampant. Scorecard diplomacy has nonetheless contributed to bringing TIP on the agenda, partly by working with NGOs. Honduras has only made slow progress on human trafficking, because the issue had to compete with other priorities in the US embassy and for the Honduran government. As a result, rather than create dedicated action plans on human trafficking, for example, Honduras had to adopt a broader national security strategy to address terrorism, money laundering, and gangs, as well as trafficking of drugs, arms, and people, problems that were all intertwined.1 The government for the most part welcomed US assistance, and efforts to combat TIP greatly improved in 2007 and 2008. However, a coup d’état in 2009 interfered with progress and US-Honduran collaboration.

The case thus demonstrates important scope conditions for creating and translating reputational concerns into action: it is difficult to create impetus for change on an issue that has relatively low salience due to other overwhelming priorities and may even run counter to the interests embedded in political corruption. Government instability easily derails cooperation. Under such conditions, however, the indirect pressure enabled by scorecard diplomacy is vital in enabling pressure from third parties.

Background

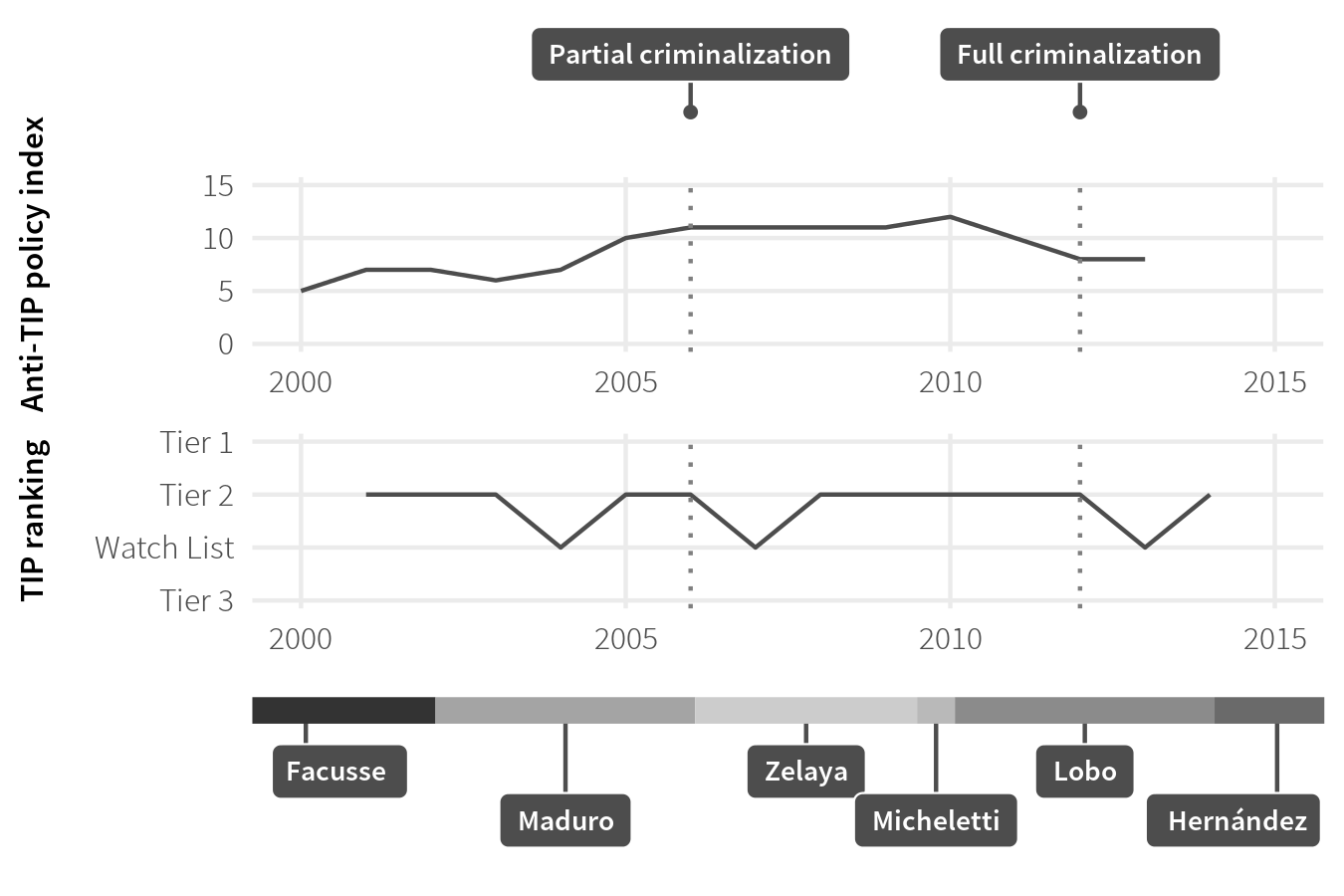

Honduras has one of the highest crime rates in the world, as well as a huge drug problem. It is poor, politically unstable, and faces high corruption on TIP issues among the immigration service. Some Honduran women and children are exploited in sex trafficking within the country, but most trafficking does not take place in Honduras. Rather, Honduras is a source and transit country for men, women, and children subjected to sex trafficking and forced labor. As Figure 5 shows, the TIP tier rating has remained either 2 or Watch List throughout the period and the policy gains have been modest.

Figure 5: Honduras’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2000–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $1,991.35 |

| Total aid | $9,847.93 million |

| Aid from US | $1,454.53 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 5.46% |

| Total TIP grants | $2,335,000 |

Table 5: Key Honduran statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

Scorecard diplomacy meetings to discuss TIP were typically at a high level. These included the minister of public security, minister of the interior, the attorney general the Director of Prosecutors, and the Supreme Court president as well as heads of the Criminal Investigative Police and Frontier Police and the inter-institutional commission on the commercial sexual exploitation of children. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2002. The cables that discuss TIP constitute 7 percent of the overall available cables, suggesting that TIP was a priority for the embassy. Scorecard diplomacy focused on the passage of anti-TIP legislation for which the US provided sample legislation. When 2005 law did not include labor trafficking, the embassy continued to press for this. The US embassy pressed for more centralized TIP data gathering and for an inter-institutional commission to discuss TIP issues. The embassy also pressed the government to address corruption among immigration officials.

Indirect pressure

NGOs have used the US TIP attention to engage with the government and increase attention to the issue. In a personal interview, the president of the Commission Against Trafficking in Persons, Nora Urbina, stressed the positive influence of the US on funding NGOs in Honduras and noted that the Commission holds a public forum on the US TIP Report every year and passes the recommendations on to the authorities.2 In addition to engaging with NGOs, the US has also funded the IOM to build capacity to assist victims of trafficking in Honduras.3 For example, the IOM used US Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) funding to hold a two-day seminar to train mid- and high-level GOH officials on TIP. The Deputy Director of the Migration Police attended the IOM training and subsequently used the seminar materials to train all of her staff on recognizing and investigating TIP.4 Thus, much of the US work went through the agents it funded, creating indirect pressure.

The media also reported on the US report and call on the government to improve. After the 2004 TIP Report that placed Honduras in a Tier 2 category, the newspaper El Heraldo called on the government to achieve the minimum standards “not only because we may lose some of the cooperation we get from the U.S. but because it’s their legal and moral obligation.”5 The media thus increased the reputational cost to the government for inaction.

Concerns

In Honduras, the main obstacle to collaboration on TIP was “massive corruption” and the accompanying poor domestic institutional capacity, poverty and related crime and corruption.6 That said, material motivations likely drove the government to collaborate with the US to the modest extent that it did. A July 2001 visit from an interagency delegation led by the U.S. Trade Representative, which decided “that the situation in Honduras [regarding labor conditions] did not warrant opening a review of CBTPA [Caribbean Basin Trade and Partnership Act] benefits,” in combination with threats of sanctions to business sectors with child labor and the possibility of a U.S.-Central America Free Trade Agreement, greatly motivated Honduras to take action on child labor.7 In 2004, a visiting US speaker reminded the government that sanctions loomed due to the Watch List ranking.8 In June 2006, the US temporarily suspended visa interviews due to passport fraud and the lack of effort by the new administration, but was encouraged by the efforts of a new “capable reform-minded Immigration Director.”9

The embassy argued that both the US-funded anti-TIP programs and TIP Report raised awareness about TIP.10 US pressure focused the government’s attention to child labor issues early on, particularly when they linked possible sanctions and a free trade agreement to Honduras’ child labor performance.11

Outcomes

Legislation

The US made some headway in pushing for criminalization, but progress has been slow. During 2004 and 2005 the US stressed the importance of legislation with several high level officials, including the Attorney General and the Supreme Court president, and Post continued to work with one of its main interlocutors, Ambassador Soledad de Ramirez (who was the Honduran Delegate to the OAS Inter- American Commission of Women) to keep the TIP issue on the agenda. The US also provided sample legislation.12 US G-TIP officials visited Honduras in February 2005 and together with embassy staff, met with key officials to get updates on current Honduran anti-TIP efforts and emphasize USG interest. Domestic officials reiterated the importance of strengthening anti-TIP legislation and stressed their commitment to doing so to US officials and details of the law and its progress were discussed at the meeting.13 In September 2005, Honduras did reform the Penal Code to cover almost all forms of Commercial Sexual Exploitation (CSE) and Trafficking in Persons (TIP), with an increase in penalties and jail time. The law was slow to be implemented; by February 2007, no cases had yet been prosecuted under the law.14 The law also did not include labor related trafficking, which continued to concern the US embassy. The TIP Report pointed out the law’s exemption of labor trafficking annually until April 2012, when Honduras finally passed a comprehensive law under pressure from the US, NGOs and others.15 Still, while the US helped urge the passage of the law, it continues to point to problems in its wording, noting for example that it “conflates human trafficking with other crimes, such as illegal adoption, and establishes the use of force, deceit, or intimidation as aggravating factors only as opposed to essential elements of the crime per international norms.”16

Domestic officials assess progress as significant. Urbina, the president of the Commission Against Trafficking in Persons, noted the importance of the US in motivating action and putting items on the policy agenda and said, “In the last 10 years, the progress in Honduras has been enormous. There is much more awareness of the issue, which has translated into prevention.”17

Institution building

After the 2007 report reiterated the US embassy’s frustration with the “extreme difficulty of extracting [TIP data] due to the [government’s] decentralized system of identifying, collecting and handling TIP cases,”18 the Honduran government began to implement a nationwide system to track all forms of criminal complaints, including TIP.19 However, data continued to be a challenge.

The US TIP office also spent about $1.5 million in Honduras between 2004 and 2012, most going to an organization called the Cooperative Housing Foundation International (CHF), which the organization used “to coordinate and streamline victim services provided by public institutions and created employment opportunities for victims to help them reintegrate into society. Global Communities also supported institutional counter-trafficking efforts by building the capacity of Honduran actors to implement the new anti-trafficking laws.”20

Promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

The embassy pressed for the government to address corruption among immigration officials, which “facilitated the trafficking of tens of thousands of persons to the United States over the past two decades.” The embassy claimed that thanks to “a few dedicated individuals” in the government, the pressure led to a move from “denial, to lip service, to meaningful efforts.”21

The TIP Report has also come to play a role in domestic policy discussions. Urbina reported that when the US ambassador submits the TIP Report, the Commission Against Trafficking in Persons holds a public forum on the issue and invites all the relevant state officials to discuss the report and stress its recommendations.22

Conditioning factors

The effectiveness of scorecard diplomacy was diminished by the huge distractions of other pressing problems as well as by disruptions in the government itself and subsequently its relationship with the US.

Major obstacles in Honduras included a much higher focus on drug trafficking and crime, endemic corruption and poverty, political instability and poor data. The TIP issue was also tied up in immigration politics. One Ecuadorian newspaper article called “Hondurans are Slaves” identified the lack of conversation on immigration policy with the US as the cause for so much trafficking. Though not explicitly so, the article portrayed the US as hypocritical for demanding a lot of Honduras for the cause without itself addressing its immigration policy that also drives the problem.

After the coup d’état of June 2009, the US halted communication with the government, which paused all TIP interaction except with NGOs until the new president was elected in January 2010. In general, collaboration has ebbed and flowed, seemingly held hostage mostly to other overwhelming priorities and poor capacity to implement and follow through. Meanwhile, any influence the US did have was facilitated by the US economic leverage and provision of assistance.

08TEGUCIGALPA165↩

Interview, phone. April 1, 2013. Conducted in Spanish by Renata Dinamarco.↩

07TEGUCIGALPA471↩

06TEGUCIGALPA459↩

04TEGUCIGALPA1384↩

06TEGUCIGALPA2130↩

02TEGUCIGALPA2916, 05TEGUCIGALPA2172↩

04TEGUCIGALPA2049↩

06TEGUCIGALPA2130↩

04TEGUCIGALPA2049; 06TEGUCIGALPA2130; 08TEGUCIGALPA429↩

02TEGUCIGALPA2916; 05TEGUCIGALPA2172↩

04TEGUCIGALPA1339_a↩

05TEGUCIGALPA456↩

07TEGUCIGALPA432_a↩

2012 TIP Report↩

2014 TIP Report↩

Interview with Ms. Nora Suyapa Urbina Pineda, president of the Comisión Contra la Trata de Personas (Commission Against Trafficking in Persons). April 1, 2013. Phone interview by Renata Dinamarco, in Spanish.↩

07TEGUCIGALPA432↩

07TEGUCIGALPA1794_a↩

“Honduras.” Web, http://www.globalcommunities.org/honduras, Accessed December 27, 2016.↩

06TEGUCIGALPA1333↩

Interview with Ms. Nora Suyapa Urbina Pineda, president of the Comisión Contra la Trata de Personas (Commission Against Trafficking in Persons). April 1, 2013. Phone interview by Renata Dinamarco, in Spanish.↩