Ecuador

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/ecuador/.

PDFContents

Ecuador demonstrated strong political will to combat trafficking and respond to scorecard diplomacy and US input. Other political factors such as political instability, however, impeded progress at times. The US actively pushed for the passage of an anti-TIP law and provided input into to its wording, to which the GOE was receptive. Scorecard diplomacy was successful in getting progress on legislation and implementation, though not as quickly as desired. It played a role in shaping understanding of the norms surrounding human trafficking, especially with difference with smuggling. The case shows the importance of individuals within the country’s government who take on TIP as a personal issue and serve as allies to US efforts, as well as the potential for political instability to disrupt these relationships. The case also illustrates the effectiveness of dropping the ratings of a country as a means to solicit a response, suggesting the value of public grading as a core function of scorecard diplomacy.

Background

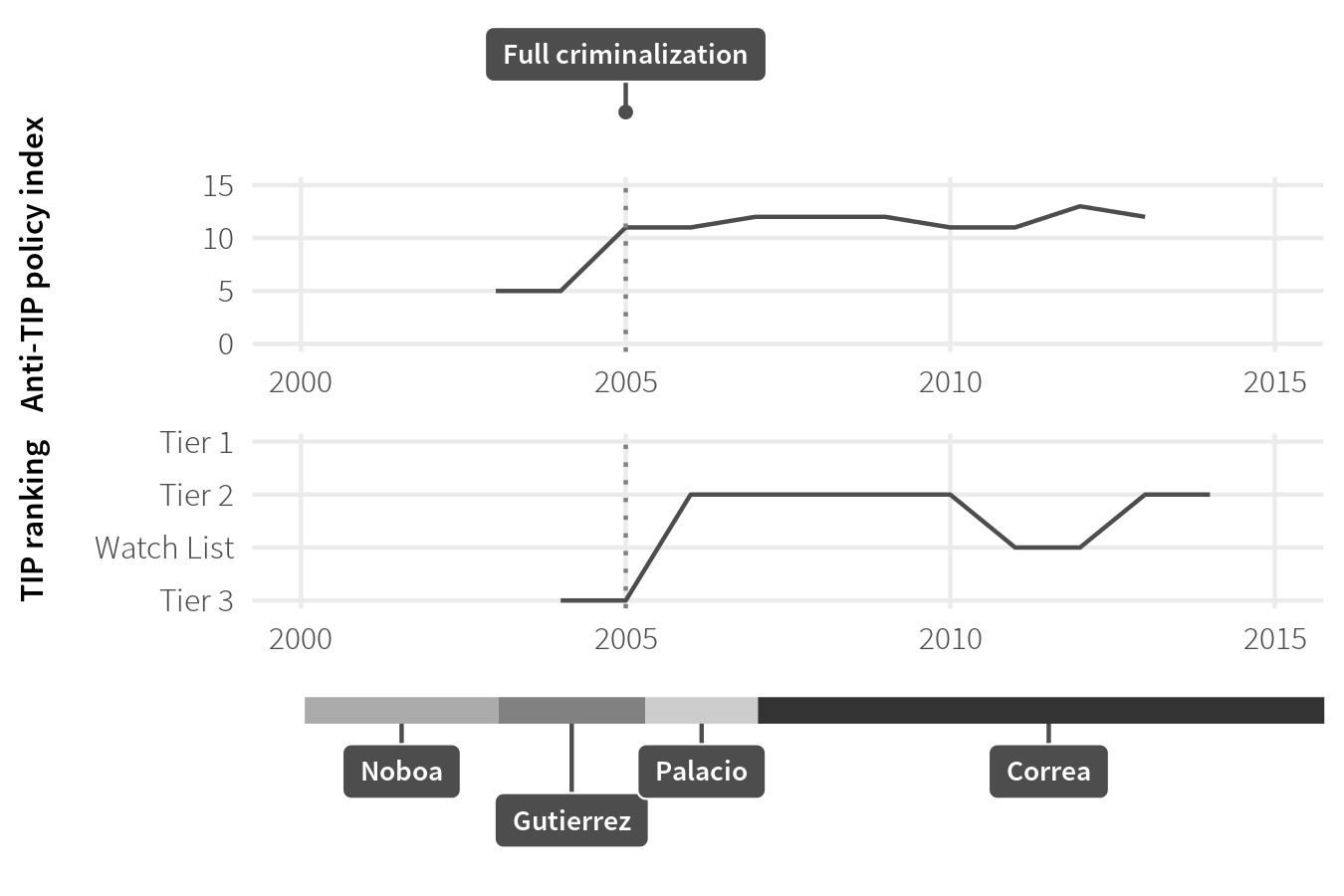

Ecuador is a source, transit, and destination country for men, women, and children subjected to sex trafficking and forced labor. Most victims are women and children who are trafficked in the domestic sex industry or forced domestic servitude, begging, or agricultural labor. Local gangs are involved in sex trafficking. Traffickers sometimes recruit children from impoverished indigenous families. Some officials are allegedly complicit by warning traffickers of law enforcement operations.1 There was little information about TIP in Ecuador for the GOE to act on until an ILO report on the subject came out in late 2003.2 The first inclusion of Ecuador in the TIP Report in 2004, which placed Ecuador on Tier 3, set off a flurry of activities in the GOE. Ecuador has since improved considerably over time, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Ecuador’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2003–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $4,461.13 |

| Total aid | $17,218.77 million |

| Aid from US | $960.61 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 2.21% |

| Total TIP grants | $7,856,032 |

Table 4: Key Ecuadorian statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

Scorecard diplomacy meetings to discuss TIP were frequent and meetings were typically at a high level such as ministers and even once directly with the President Alfredo Palacio. A key figure was the minister of government. Other interlocutors included the foreign minister, the director of gender affairs, the Human Rights Director in the ministry of foreign affairs, the first lady, the acting attorney general, the president of congress, and the national chief of police, among others. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2004 and is most intensive between 2004-2007. The cables that discuss TIP constitute 8 percent of the overall available cables, suggesting that TIP was a top priority for the embassy. Indeed, A US TIP delegation visited Ecuador shortly after the first time Ecuador was included in a TIP Report in 2004 to drive home the message and work to formulate policy responses.3 The US embassy developed a strong relationship with Minister of Government (MG) Raul Baca, who reported on his progress within the GOE or requested US support in specific areas. Scorecard diplomacy focused on the passage of anti-TIP legislation and the embassy commented directly on versions of the text. The embassy also often stressed implementation issues and the US funded education programs and training programs, including shelters and a child protection police unit. Indeed, Ecuador has received a large share of TIP grants. The US also pushed for the assignment of a special prosecutor and specific persons for appointments and positions within the government. The embassy also pushed to start an inter-institutional commission on trafficking. Importantly, US officials repeatedly sought to educate government officials about the nature and scope of TIP and the difference between TIP and smuggling.

Indirect pressure

The release of the first TIP Report launched the issue of human trafficking into the spotlight of the media. According to Minister of Government Raul Baca, TIP was getting attention in the media, and civil society had organized marches to demand action from the GOE.4 This public attention augmented the pressure from the report. The media was also attentive to the progress of TIP legislation.5

Several other actors contributed to anti-TIP policy in Ecuador and cooperated with the US. The ILO opened a new shelter that the US officials visited. The US funded the IOM and CARE International to implement anti-trafficking prevention activities. The US also met with and funded several NGOs, both domestic and international.6 For example, US funds helped the American Bar Association advise on legislation.7 Thus it appears that the US was able to fund organizations to help reinforce its message.

Concerns

While its evident that Ecuador was extremely open to US advice, the source of this openness is not clear. The record provides little information about whether Ecuador’s government cared about sanctions or was concerned with reputations. There is no record of Ecuadorian officials initiating discussions about possible sanctions, but in 2005 the Ecuadorian embassy staff sometimes mentioned the possibility of sanctions to domestic officials.8 Officials also did not explicitly express concerns about Ecuador’s reputation. The government didn’t express anger about harsh ratings, but did say that they wanted the rating to improve.9 When Ecuador received a Tier 3 rating in 2005 the president went on national television to tell people that he cared about trafficking.10 In general, drops in Tier ratings were particularly successful in capturing the GOE’s attention, suggesting the Tier ratings mattered.

The US efforts in Ecuador contributed to the salience of the issue, but an important factor in making a real dent in TIP was the government’s own desire to fix the problem. Often it appeared individuals drove this willingness. While some officials may not have taken an interest in TIP prior to US engagement, once the embassy brought the severity of the issue to their attention, many became personally invested. In 2006, the embassy said it seemed that “motivation to improve comes more from within than from embassy prodding,”11 which likely explained much of the progress the GOE made.

Outcomes

Legislation

The U.S. pushed passage of anti-TIP legislation, contributed to the wording of the legislation, and continued pressing for implementation after its passage. During the first few years of the TIP Report, the US pressured the GOE to pass an anti-TIP law, and the embassy and the American Bar Association (ABA) contributed significantly to the wording of the legislation, also working directly with the Supreme Court and the National Council of the Judiciary on the issue. 12 Shortly after the 2004 TIP Report placed Ecuador on Tier 3, the government began work on a comprehensive anti-TIP bill. On September 6, the President Gutiérrez sent a bill of penal code reforms related to TIP to Congress.13 Three days later, the ambassador met with the President of Congress and pushed him to get Congress to address TIP legislative reforms; he was soon after told that Congress would prioritize the bill, including by President Gutiérrez.14 Multiple bills on TIP were pending in Congress and being reviewed and pushed for by the embassy,15 and they were soon combined into one bill that defined TIP in compliance with G/TIP model legislation.16 Several government officials promised the embassy they would push Congress to pass the bill.17

The GOE gave the embassy opportunities to comment directly on the wording as the law was being drawn up.18 At one point, the Ecuadorian Supreme Court asked the American Bar Association for help in drafting the law, and the US TIP office funded the ABA to visit Ecuador multiple times.19 The government incorporated the ABA’s suggestions into the bill.

Unfortunately, political instability slowed progress, but meetings with high- level officials to press the issue kept it at the top of the agenda even amidst the political turmoil. The eventual ousting of President Gutiérrez slowed even progress further, but the embassy “redoubled” its efforts on TIP, despite the new administration being less pro-American.20 Eventually, the law passed.

Afterwards, the USAID met with over 40 US and Ecuadorian government officials, civil society, and international donors to assess needs with regards to implementation.21 The US funded education programs and training programs that were part of government policy implementation. For example, the US sometimes funded training for law enforcement and other officials. The US also funded various projects, mainly through USAID, including shelters and the child protection police unit DINAPEN within the ministry of the interior.22 The embassy suggestion to the attorney general to assign special TIP prosecutors was followed by increased prosecutions. As a whole, the interaction suggests that the US was fairly successful in getting progress on legislation and implementation, though not as quickly as desired.

The political turmoil caused by the 2010 crisis, in which the National Police rose up against President Rafael Correa, detracted from attention to TIP. In 2011 Ecuador was demoted to Tier 2 Watch List. By January 2013, a new criminal code more than doubled minimum sentences for human trafficking,23 and prosecutions and convictions increased.

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

Through repeated meetings, US officials sought to educate government officials about the nature and scope of TIP.24 The US embassy strove repeatedly to help the government officials understand the difference between TIP and smuggling and funded the ABA to train officials on the difference.25 In 2004 the UN and the ministry of foreign affairs co-sponsored a two-day conference. Participants, including officers from the police unit dedicated to protecting children, repeatedly confused smuggling and trafficking. The U.S. additionally taught Ecuadorian officials about TIP by providing them examples from their own policies. Ecuadorian officials also visited the US in October 2005 to learn about TIP policy.26

Institution building

The embassy also pressed for specific appointments and positions within the government. They got Minister of Government Raul Baca to seek and receive appointment as Official TIP Coordinator. In 2005 they proposed to Foreign Minister Carrion that he chair the inter-ministerial TIP working group (though there is no indication whether he did so).27 The Ecuadorian government also sought out the embassy’s involvement. The Ministry of Government invited the embassy to help start the inter-institutional commission to create a national TIP plan. The embassy used the opportunity to push for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to also be involved in the commission.28 This US involvement with the action plan continued for years.29

Conditioning factors

In Ecuador, the embassy’s personal interactions were very important. Meetings went all the way to the president in 2005. The US met frequently with high- level officials whom the embassy sought and often succeeded to get personally invested in TIP. A prime example is their recruitment of First Lady Maria Paret as a spokesperson and activist for TIP through her position as director of the National Institute of Childhood and Family (INNFA). Certain figures within the Ecuadorian government, including MG Baca, First Lady Paret, and prosecutor Lucy Blacio were crucial in the fight against TIP. The embassy described Baca as “a rare Gutiérrez administration bright light.”30Allies such as these who prioritized TIP helped enact change from within the government.

Indeed, the revolving door of the minister of government’s office after Baca’s resignation underscored the importance of a steady interlocutor.31 The embassy remained in close contact with the new minister, whom they had some success cultivating.32 But he resigned quickly, making him the fourth to resign in Gutiérrez’s two years in power. The embassy was not even able to meet the next minister before he too resigned after only a month, and his replacement was ousted a few weeks later when Congress voted President Gutiérrez out of office. This political turmoil and the repeatedly changing contacts prevented the embassy from reestablishing the strong cooperation they had with the Ministry of Government on TIP, demonstrating how political shifts can significantly disrupt embassy relationships and progress on TIP.

Other obstacles to progress included the government’s lack of understanding of the difference between trafficking and smuggling. Fortunately these were balanced by some favorable conditions such as strong political will on behalf of the Ecuadorian government, US economic aid, and intensive US-funded training programs.

2015 TIP Report↩

US TIP Report 2004↩

04QUITO2198↩

04QUITO2447↩

04QUITO2519↩

“Anti-Trafficking Technical Assistance: Ecuador Anti-Trafficking Assessment,” USAID, August 2006, http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnadh204.pdf, Accessed December 27, 2016; 04QUITO2519; 04QUITO2773; 04QUITO3132; 05QUITO369.↩

05QUITO179, ABA received two grants in 2004 ($370,798) and 2005 ($395,942).↩

05QUITO553↩

05QUITO78, 05QUITO1273↩

05QUITO1803↩

06QUITO2428↩

04QUITO2773 05QUITO224. American Bar Association, “Ecuador Programs,” http://www.americanbar.org/advocacy/rule_of_law/where_we_work/latin_america_caribbean/ecuador/programs.html↩

04QUITO2519↩

04QUITO2459, 04QUITO2571, 04QUITO2980↩

04QUITO2773↩

04QUITO2861↩

04QUITO3099, 04QUITO3257↩

04QUITO2861_a. For the work of the ABA, see ABA Journal, 4/6/2006, “SINISTER INDUSTRY: ABA Joins Worldwide Effort to Fight Criminal Trade in Human Beings.”↩

American Bar Association, “Ecuador Programs,” http://www.americanbar.org/advocacy/rule_of_law/where_we_work/latin_america_caribbean/ecuador/programs.html; 04QUITO2595; 05QUITO179; 05QUITO224↩

05QUITO78, 05QUITO224, 05QUITO490, 05QUITO534, 05QUITO995,↩

“Anti-Trafficking Technical Assistance: Ecuador Anti-Trafficking Assessment,” USAID, August 2006, http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnadh204.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2016↩

06QUITO2428↩

US TIP Report 2014↩

05QUITO995↩

05QUITO224, 04QUITO2861_a, 04QUITO3257↩

05QUITO2890↩

05QUITO2506↩

05QUITO2762↩

08QUITO696↩

04QUITO2598↩

04QUITO2598↩

05QUITO61, 05QUITO78↩