Chad

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/chad/.

PDFContents

Despite considerable engagement between the US and Chad, little progress has been made due to other national concerns such as internal political conflict, ethnic violence, regional instability and the need to support the fragile peace that finally ensued in 2010, after which Chad remained actively engaged in fighting anti-government armed opposition groups that crossed into the country. As a result, Chad has not been able to pass legislation despite US pressure to do so, but the US has remained involved and funded IGOs to work on the topic. Chad and the US also disagreed on what constitutes trafficking, and the US has not been able to change the mindset.

The case thus illustrates the difficulties of cultural barriers to how trafficking is defined and the challenge of using scorecard diplomacy to influence policy when the government faces more imminent domestic turbulence. In some ways Chad was an inverse perfect storm: multiple conditions for lack of influence were present.

Background

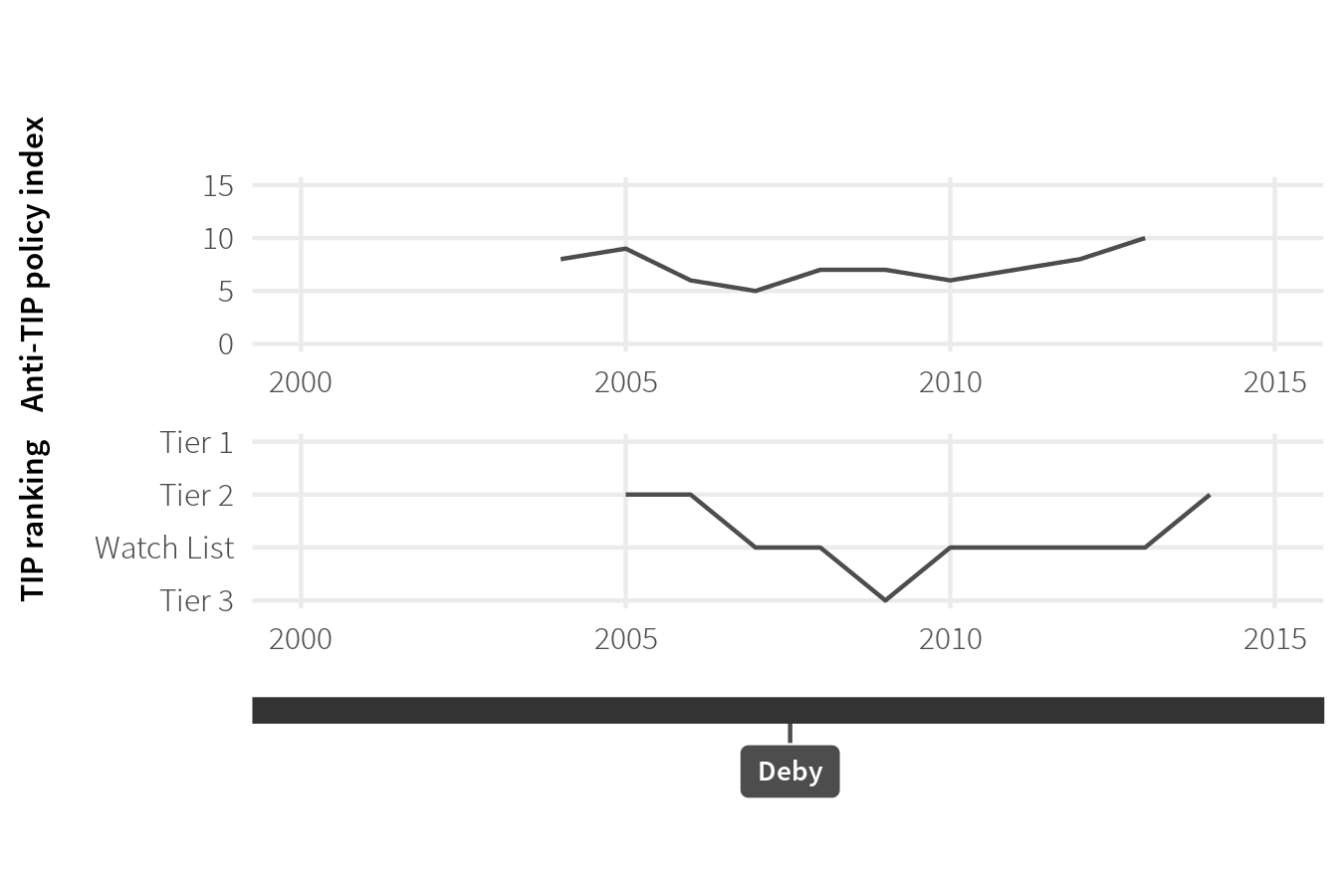

One of the poorest countries in Africa, Chad faces problems with trafficking and exploitation of children for begging, prostitution and labor. The trafficking problem is primarily internal, and frequently relatives, teachers, or intermediaries entrusted with the care of children will subject them to forced labor in domestic service or herding and begging. Children are sometimes sold in markets for use in cattle or camel herding. In addition, the Government also uses children for military service. As Figure 3 shows, Chad has had flat tier ratings, starting and ending as a Tier 2 country, with worsening in ratings in the late 2000s. The policy outcomes have also remained rather unchanged.

Figure 3: Chad’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2004–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $770.75 |

| Total aid | $6,564.27 million |

| Aid from US | $1,273.57 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 6.33% |

| Total TIP grants | $1,302,555 |

Table 3: Key Chadian statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

Although scorecard diplomacy on trafficking was not as intensive as in some other countries, when they occurred, meetings were often at a high level such as the foreign minister, the national mediator, the minister of human rights, the minister of justice, and various Secretary Generals. The ambassador also discussed TIP with President Idriss Deby. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2005 when Chad was first included in the TIP report. The cables that discuss TIP constitute 5 percent of the overall available cables, but the documentation overall is not very rich, suggesting less intensive efforts. The US applied pressure through downgrades and reminded Chad of possible sanctions, and in the absence of a responsive government, it sought, as discussed below, to work though facilitation of collaboration between all stakeholders including government, civil society and IGOs. The embassy encouraged the creation of an inter-ministerial committee to undertake the initiatives recommended by the US Action Plan. Scorecard diplomacy also sought to educate about the nature of human trafficking to counter local norms.

Indirect pressure

The cables recount some involvement between the US and IGOs or local NGOs. “In 2006,” according to one cable, “the US funded a UNICEF project to create a child protection network to carry out the rescue and rehabilitation of 1,500 child herders, 500 child domestics and 500 victims of commercial sexual exploitation, while also covering the production costs of a locally-made film that depicts the plight of child herders in Chad.”1 The embassy also discussed the recruitment of refugees by a Sudanese rebel group with the UNHCR.2 Finally, the embassy encouraged the government to collaborate more with NGOs.3 The IOM and the US have had a strong partnership in Chad. In 2012 the IOM launched a major study as part of a two-year US State Department- funded project: “Strengthening Chad’s Capacity to Prevent and Combat Trafficking in Persons.”4

Concerns

Despite its heavy aid flows, neither concerns about aid nor image have prompted serious efforts to improve Chad’s rating or to take up the fight against trafficking in earnest. Although the US discussed possible sanctions in 2009 with officials, in reality the US gained little from economic leverage in Chad. Impending sanctions were brought up to no avail.5 Indeed, the US embassy assessed its own economic leverage as weak, because the US offered less assistance to Chad than other countries, which were more influential.6 Concerns about image were dwarfed by on-going conflicts. Furthermore, different domestic understandings of trafficking have mitigated the reputational costs of some forms of trafficking.

Outcomes

Legislation

Chad has not succeeded in passing specific anti-TIP legislation, partly because political interests worried about implications for practices such as child herding and child employment more generally.7 Although interaction continued at a ministerial level, by late 2008, draft legislation had yet to emerge from the Ministry of Justice and the stalemate continued despite the ambassador raising possibility of TIP sanctions being raised at the highest levels of governments.8 In 2009, Chad was finally downgraded from a Tier Two Watch List to a Tier Three. Not even this downgrade promoted any real action on TIP legislation, as many issues diverted attention from TIP issues.9 The embassy began to meet regularly to press for legislative progress.10 Due to congressional limits of how long a country can stay on the watch list, in 2014 the State Department faced a choice between downgrading Chad to Tier 3 or upgrading it to Tier 2. Noting an increase in prosecution, convictions and an awareness raising campaign, it went with the upgrade to Tier 2, although the draft legislation to criminalize child trafficking still lingered for a fourth year. In March 2014 the government began drafting comprehensive anti-TIP legislation. The UNODC organized a technical workshop on the draft law in March 2015 that brought together “legal practitioners, academics, sociologists, members of civil society, government departments involved in the topic, as well as representatives from international organizations.”11 Notably, the event was funded by the US Department of State. Hopeful of progress, the US maintained Chad at Tier 2 in the 2015 report.

Institutions

The 2009 downgrade prompted Chad to form an inter-ministerial committee able to undertake the initiatives recommended by the US Action Plan.12 The committee met in 2009 but was not permanent. 13 In 2013 Chad was placed on the Watch List for a fourth year and avoided the mandatory downgrade only because they had produced a written plan. As part of this plan, the government finally formally created an inter-ministerial committee on trafficking in persons to coordinate all government efforts to combat trafficking. The committee convened for the first time in March 2014, but funding was slow. By 2015 the TIP Report notes that the committee regularly convened.

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

There is no evidence in the cables or elsewhere that the US diplomacy has succeeded in changing the norms or understandings of TIP in Chad. Domestic practices surrounding child labor, including as soldiers for the government itself, and child herding have remained accepted and presented additional barriers to progress on trafficking.

Conditioning factors

Facilitating factors in Chad were few, which is why progress remained limited. Meanwhile, obstacles abounded, including regional instability, anti-government armed resistance, and a weak judicial system. During this time, “Chad was actively engaged in fighting anti-government armed opposition groups that crossed into Chadian territory.” 14 The country was therefore clearly dealing with other issues that could have diverted its attention from TIP issues.

Another obstacle in Chad was the serious conflict between definitions of human trafficking and cultural norms and practices, such as cultural sensitivities surrounding child labor. Although specific anti-trafficking legislation had already been cleared by the Council of Ministers in 2006,15 domestic opposition stopped it in an effort to accommodate provisions to the practice of using children as cattle herders,16 because extreme poverty drives parents to essentially sell children for this purpose, sometimes for as little at $20.17 The Government itself was also using children for military service, making it very difficult to make progress.

07NDJAMENA61↩

08NDJAMENA541↩

09NDJAMENA230↩

“Chad Human Trafficking Challenge: IOM Report,” International Organization for Migration, 10 Jun. 2014, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.iom.int/news/chad-human-trafficking-challenge-iom-report.↩

09NDJAMENA111, 09NDJAMENA128↩

09NDJAMENA143↩

07NDJAMENA89, 09NDJAMENA230↩

06NDJAMENA821, 07NDJAMENA879, 08NDJAMENA439, 09NDJAMENA128↩

10NDJAMENA105↩

09NDJAMENA137↩

“Chad Strengthens Legislation Against Human Trafficking Thanks to UNODC Support,” UNODC, n.d., accessed 26 Dec. 2016, https://www.unodc.org/westandcentralafrica/en/chad---anti-human-trafficking-law---25-26-march-2015.html.↩

09NDJAMENA258↩

09NDJAMENA290↩

10NDJAMENA105↩

06NDJAMENA821↩

07NDJAMENA89↩

“Children Sold Into Slavery for the Price of a Calf,” IRIN, 21 Dec. 2004, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://www.irinnews.org/report/52490/chad-children-sold-into-slavery-for-the-price-of-a-calf.↩