Armenia

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/armenia/.

PDFContents

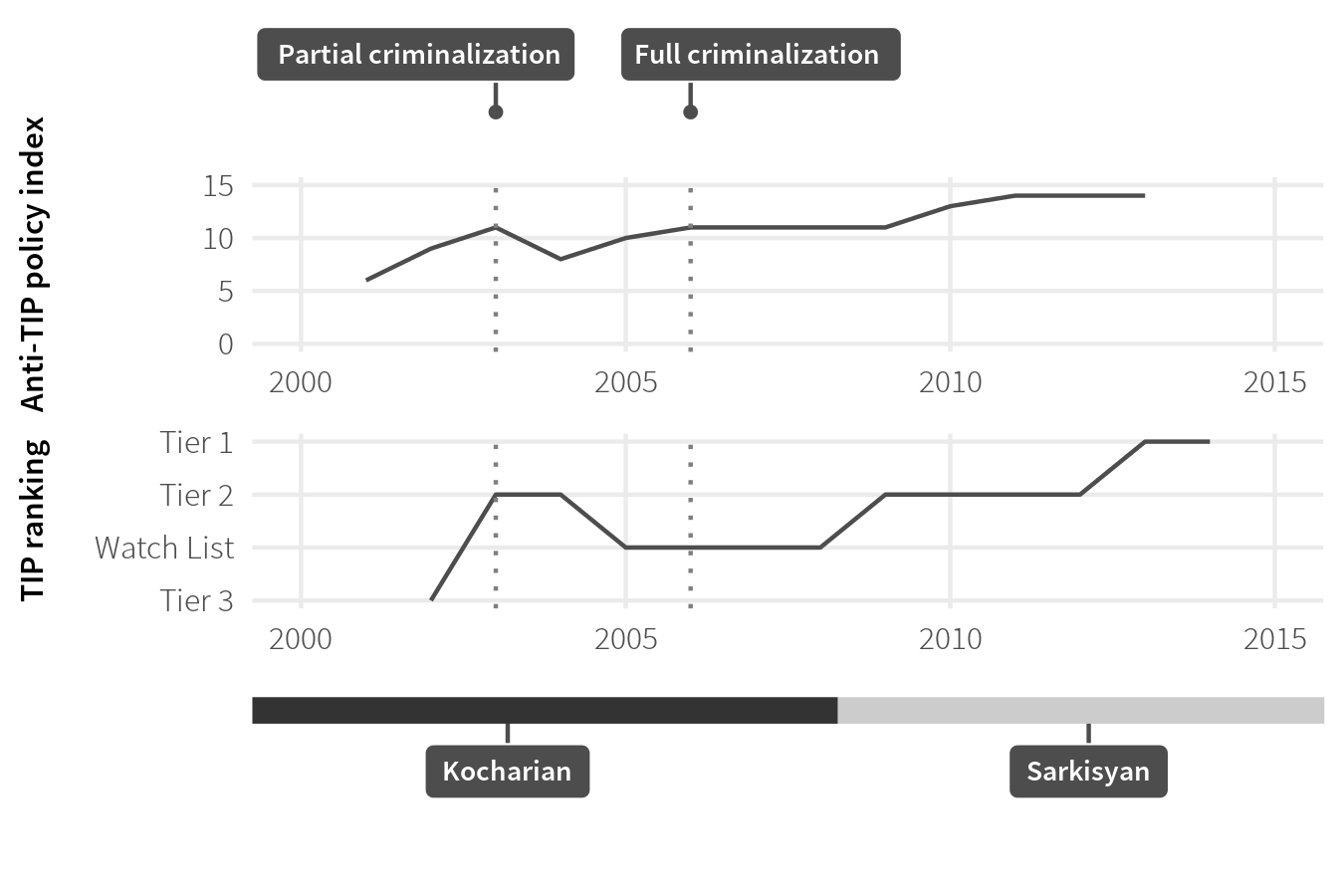

Armenia illustrates the progress that can be made by generating reputational concerns using public ratings. Since 2001, the Armenian government has made substantial improvement on an extensive trafficking problem. The government was highly motivated to improve its Tier ranking, comparing itself with other countries. As seen in Figure 2 Armenia started out as a Tier-3 country in 2002. In the early years, officials tended to view human trafficking as a problem for donors to solve, and the US pushed hard for the country to take ownership of the problem. Legislation was passed in 2006, but not until 2009 did the government start to take responsibility for the issue and give it higher priority. Through close collaboration with the embassy, by 2013 it reached Tier 1, where it has remained since. The embassy also worked with the IOM, OSCE, and NGOs and cultivated a set of “reliable anti-TIP interlocutors” in the government.1 The willingness in 2009 of a new deputy prime minister who had a good working relationship with the US embassy, Armen Gevorkian, to invest himself in all aspects of the issue further facilitated cooperation.2 In addition, the US took part in many practical assistance programs to fight TIP.

The case demonstrates progress that was driven by the concern for the Tier ranking, which opened up opportunities for close diplomatic engagement. This underscores the basic argument about reputational concerns. It also shows the value of good working relationships and of indirect augmentation of the scorecard pressure through collaboration with civil society and IGOs. Finally, it illustrates how the information gathering that the TIP Report brings can focus attention and contribute to changes in domestic practices.

Background

With its central location to Eastern Europe, Asia and the Middle East, Armenia is a source and, to a lesser extent, destination country for men, women, and children subjected to sex and labor trafficking. Women and children are increasingly subjected to sex and labor trafficking and forced begging within Armenia. Armenian victims sometimes end up trafficked to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Turkey, whereas Chinese women sometimes are trafficked into Armenia. Children often work, making them vulnerable to trafficking. As Figure 2 shows, the country has experienced every rating on the tier scale, consistently graduating from bottom to top with the policy index also indicating accompanying success. The gains have been particularly pronounced during the regime of President Serzh Sargsyan.

Figure 2: Armenia’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2002–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $2,795.46 |

| Total aid | $7,017.22 million |

| Aid from US | $1,378.93 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 6.61% |

| Total TIP grants | $1,728,605 |

Table 2: Key Armenian statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

Scorecard diplomacy on trafficking was a high priority for the US embassy, and meetings were frequent and at a high level and the embassy worked to build strong interlocutors. Meetings included the deputy prime minister and minister of territorial administration, the deputy foreign minister, members of parliament, the deputy defense minister, a presidential national security adviser and on several occasions the cables not that the issue rose to the level of the president. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2002 and is most intensive in the years 2002-2006. The cables that discuss TIP constitute 5 percent of the overall available cables, suggesting that TIP was a highly discussed topic in general. In the early years, the US pushed domestic officials to take ownership of the trafficking issue. The TIP report and local embassy pressured the government to address official complicity in trafficking and to increase prosecutions. Initially some officials were in denial. Lack of official recognition of the problem within many sectors of the government, however, contributed to the overall lack of progress. In 2005 the Minister of Justice declared that “trafficking does not exist as a phenomenon in Armenia.”3 Scorecard diplomacy also focused on reorganizing the domestic administration and oversight of TIP policy, increasing inter-agency anti-TIP cooperation, and ensuring that the TIP commission had clout and was staffed well. The embassy also offered input into the content of anti-trafficking law and pushed for stricter penalties and full criminalization. Scorecard diplomacy also included legislative assistance offered through the OSCE and a resident legal advisor, as well as grants to support the strengthening of law enforcement and victim referral.

Indirect pressure

Multiple international organizations and actors were at work in Armenia. The US cooperated extensively with and funded the IOM and the OSCE efforts. They praised the work of the OSCE, which with US support helped organize an exhibition in Yerevan to raise awareness about TIP.4 The US also funded a survey on TIP that the IOM initiated and carried out, an IOM program for a hotline to assist victims, another program to provide safe havens, and yet another for writing a manual for the diplomatic core offering guidelines for interviewing and repatriating TIP victims.5 As noted, the US also funded the OSCE legislative assistance efforts to advise on the substance of legislative reforms. It has also interacted frequently with the NGO community, which has been aggressive in fighting TIP and skeptical of the government efforts, using NGOs as a source of information on TIP and funding research.6 The Armenian government, knowing this, sought to sometimes pressure and at other times work with the NGOs, who had to walk a fine line between influencing and being pressured. As the government became more accepting of the TIP problem, collaboration with NGOs became more constructive.7

The media also enhanced scorecard diplomacy in Armenia by covering the report and being specific about its criticisms,8 although at times the government has also used the media to criticize the report’s integrity.

Concerns

The government was candid that it was motivated to improve its Tier rating. For example, after the 2004 report came out, the head of the Armenian government’s Migration and Refugees Department told local media that Armenia’s Tier 3 rating in the first 2002 report shocked the government into action: “This assessment of Armenia was like a cold shower, as their approach was very strict and unexpected. In any case, we were not disappointed ending up in such a situation, but were given an incentive and concentrated all our efforts on making the fight against trafficking more organized.” He displayed reputation- as-image concern as he continued, “It is clear to the world that in Armenia, not only do we understand the importance of fighting trafficking, we also take certain effective steps,” noting specifically Armenia’s desire for “integration into European structures.” 9 Armenian officials also echoed this sentiment directly to the US officials, whom they told that Armenia was “anxious to portray itself as an ally to UN and other International arenas in this fight”10 and that they hoped for US support in Armenia’s efforts to join the UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice.

It was clear that Armenia saw their TIP report ranking as an issue where status vis-à-vis other countries was relevant. In 2007 the Armenian government drew up a detailed report to compare Armenia’s report with that of Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Georgia, “highlighting differences in the three countries’ performance which seemed decisive in Armenia’s neighbors being graded higher than Armenia.”11

Officials’ concern with image was also evident in officials’ repeated practice of agreeing privately with the US while publically criticizing the report.12 In 2005 the US downgraded Armenia to the watch list, criticizing, among other things, trafficking penalties as too mild. The US allegations of official complicity in trafficking motivated the government to clear its reputation. Although the prosecutor denied any evidence of such official complicity,13 prosecutions in general increased in the fall of 2005.14 Armenian officials and NGOS met specifically to discuss trafficking in advance of the embassy’s submission of the 2006 TIP Report and urged all agencies to submit information to the embassy.15 Tellingly, after the 2006 report, the government dismissed the accuracy of the report in public, but President Kocharian called a high- level meeting to discuss the issue, and officials privately remained very accepting and appreciative of the legal advice on the legislation.16

Illustrating the “status maintenance” mechanism discussed in chapter 1, domestic attention has continued on keeping the Tier 1 rating earned in 2013. In 2015 the media reported widely on the report, noting, “The Republic of Armenia has maintained its Tier I status for a third year in a row in the US State Department’s 2015 Trafficking in Persons assessment.” They once again stressed the reputation-as-image concern, continuing, “Armenia is among just 31 countries out of 188 to have achieved Tier I status.”17

Finally, the case also suggests the officials may take personal pride in an issue as discussed in Chapter 2 of the book. One cable updating Washington on the TIP situation notes that “The GOAM finally took our advice on this in 2008, appointing the Deputy Prime Minister/Minster of Territorial Administration Armen Gevorgian as chair, and this new structure has indeed energized government efforts. Gevorgian seems to have taken on the TIP issue as something that will fro personally, and has engaged himself energetically in the policy issues.”18

The US also provided great assistance to Armenia, which may have influenced government responses. As a former US ambassador explained, “It was an embassy mostly about assistance. So the threat to assistance was taken very seriously by us and by the Armenians.”19 Local Armenian media speculated that the threat of sanctions could have contributed to the creation of the commission.20 That said, no public documented discussions of sanctions between US and Armenian officials exist.

Outcomes

Legislation and other policy

The US had a heavy hand in pushing for anti-TIP policy. In April 2003, Armenia amended its criminal code to criminalize trafficking for sexual exploitation. The US TIP Report was cataclysmic, a fact stressed both by local NGOs, 21 IGOs, and government officials.”22 An IOM official noted that the organization’s initial efforts had fallen flat, but that “It was only after the US State Department’s report that the government decided to take action and to work with the IOM.”23 The US continued to play a strong role in legislative reforms, sometimes offering specific —and often well-received— advice on the wording of the legislation and also sending a legal adviser to work on the law.24 At other times the US worked primarily through the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which it funded to analyze the legislative gaps.25 For several years the embassy pushed for full criminalization and stricter penalties. The eventual strengthening of penalties can be linked directly to interactions with the US about Tier ratings and criticisms in the US TIP Report.26 By funding the OSCE legislative assistance efforts and sending a resident legal advisor, the US advised on the substance of legislative reforms. Parliament amended the Criminal Code in June 2006, following much of the US advice provided through the OSCE and other channels.27

The embassy continued to pressure the government to pass a new action plan and fund it properly, which eventually occurred.28 The US legal advisor assisted in the formulation of the Action Plan.29 The embassy also pushed on issues such as official complicity in trafficking and increasing prosecutions of such cases. The US funded grants to support the strengthening of law enforcement agencies’ response to trafficking, including separate grants for training in victim referral and training in investigating trafficking cases. By 2009, more vigorous prosecutions were starting, with, in one major case, the embassy noting, “This is the type of vigorous prosecution that the USG applauds, and which it has been training and pushing the GOAM [Government of Armenia] to pursue for years …[]… We continue to see and welcome the new level of maturity and willingness by Armenian law enforcement and the judiciary to address the trafficking issue seriously.”30

Armenia’s success is far from complete, but its progress has been remarkable. Right from the beginning, the US frequently discussed the issue with high-level government officials, who showed concern about the US Tier rating and sought concrete information for how to improve their rating. The embassy reported that concrete results often followed the discussions.31

Later developments bear mentioning. The 2014 TIP Report pushed the country on its efforts to identify victims of forced labor. Some progress was reported the next year when the reports noted that the government enhanced efforts to protect identified victims by adopting the Law on Identification and Assistance to Victims of Human Trafficking and Exploitation, but it still had not completed reforms to improve labor inspections.

Institution building

The US was involved with policy in several ways. It advised the government to reorganize the domestic administration and oversight of TIP policy. Following the criticism by US and other international actors, in October 2002, the prime minister decreed the creation of a government commission to address TIP and to start designing an action plan including new anti-TIP provisions into the Criminal Code. 32 The Commission agreed to use the anti-TIP website that the US funded for Armenia.33

Indeed, Armenia illustrates the information gathering effect well. In February 2005, the Inter-Agency Anti-Trafficking Commission met to discuss the government’s anti-TIP efforts. They timed the meeting specifically before submission of information to the embassy for its filing to Washington for the TIP Report. Representatives from the Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, Department for Migration and Refugees, and others participated, as well as IGOs and NGOs. The discussions revealed a lack of inter-agency communication, which participants pledged to improve. The ministry chairing the commission encouraged all participants to send the US embassy a detailed summary of their anti-trafficking work before the TIP filing deadline. A representative of Armenian law-enforcement recommended that permanent staff be assigned under the Commission to improve its effectiveness. The US embassy reported to Washington that “This meeting of the Commission, as well as previous such gatherings, demonstrates that the USG’s TIP report is one of the principal driving forces for the activities of the Government Anti-TIP Commission … As the Commission reviews the implementation of the National Action Plan on Combating Trafficking (2004-2006) and prepares its own report and recommendations to the Government, it is clear that the USG’s report is serving as a catalyst for interagency anti-TIP cooperation and is setting the Commission up as a more effective tool in coordinating the GOAM efforts on fighting TIP.34 That the TIP reporting requirements spurred these meetings is a good example of how the information gathering that the TIP Report brings can focus attention and thus contribute to changes in domestic practices.

The embassy put considerable pressure on the government to increase the commission’s power.35 Years later, after repeated US efforts to push national TIP policy to a higher administrational level, the commission was elevated to a council with more decision making powers.36 The embassy also successfully pushed for the appointment of a specific person as chair37 and through numerous meetings with interlocutors, who on US urging took the issue to the prime minister, got approval of budget requests for TIP policies.38 Embassy officials assessed that the TIP reporting requirement was “serving as a catalyst for interagency anti-TIP cooperation and…setting the Commission up as a more effective tool in coordinating the GOAM efforts on fighting TIP.”39 The US also funded Armenian officials to travel to destination countries to facilitate cooperation issues with these countries, funded the creation of a training manual for the diplomatic core in how to work with victims, and “conducted an anti-trafficking seminar for judges, prosecutors, investigators and police,” as well as other domestic capacity-building grants.40

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

Furthermore, the US embassy worked hard to change the mindset of Armenian officials. From the early years the embassy stressed the need for Armenia to “take ownership” of the issue.41 Over the years, this began to happen. As the deputy prime minister noted in late 2009, “mentalities” about trafficking had begun to change for the better, and US efforts had brought the issue to the fore: “it wasn’t the case four years ago that trafficking was so frequently discussed in the government.”42

Armenia exemplifies how the TIP Report can serve spread information about practices by other countries. As noted earlier, in 2007, one of the embassy’s TIP interlocutors asked the embassy for feedback on a Ministry of Foreign Affairs report that compared Armenia’s policies with the reports for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Georgia to understand what was leading to better ratings and said that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs would then target their efforts on those areas where Armenia was deficient.43

Conditioning factors

Major obstacles to TIP progress in Armenia included the scope of the problem, extensive official complicity, and poor domestic capacity. In several cases the government was slow to prosecute suspected officials. The US also had to push hard to get the government to allocate resources to the problem. An internal political crisis of 2008 slowed progress further.44 The embassy enjoyed strong relationships with many dedicated officials and cultivated “reliable anti-TIP interlocutors,”45 but complained that these interlocutors lacked sufficient authority.46 These factors all worked against US scorecard diplomacy.

However, several factors also facilitated engagement. The embassy was heavily engaged and prioritized the issue at a high-level, leading to the development of consistent relationships. The authority of reliable interlocutors rose with the ascension to power of Deputy Prime Minister Gevorgian, who also became Chairman of the newly established Ministerial Council to Combat Trafficking and with whom the embassy had good relations.47 The ascension of Gevorgian facilitated greater attention to the issue and subsequent progress. In addition, the US had some leverage through its sizeable assistance program, including assistance targeted at TIP problems. US efforts to use scorecard diplomacy were also bolstered by Armenia’s concern for its international and domestic reputation, demonstrated by its sometimes vigorous attacks on the US report in the media while privately cooperating. Finally, the case was helped by cooperation with IGOs, especially the OSCE and the IOM, and local NGOs.

07YEREVAN691↩

09YEREVAN865↩

As reported in the 2005 TIP Report discussion of Armenia.↩

Text: Exhibition against Trafficking of Women Opens in Yerevan; Dept. of State, USAID, American Bar Assoc. among supporters.” State Department. (November 18, 2002 ): 448 words. LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2012/02/21↩

04YEREVAN1344, 06YEREVAN895↩

04YEREVAN1344↩

06YEREVAN1161, 07YEREVAN351↩

See for example 05YEREVAN1091↩

Armenian official upbeat on fight against human trafficking.” BBC Summary of World Broadcasts. (June 18, 2004, Friday): 662 words. LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2012/02/21↩

04YEREVAN1639↩

07YEREVAN888↩

06YEREVAN836↩

05YEREVAN2001↩

05YEREVAN2051↩

06YEREVAN214↩

06YEREVAN836↩

“Armenia Maintains ‘Tier 1’ Status in the 2015 Trafficking in Persons Report,” Asbarez, 28 Jul. 2015, accessed 26 Dec. 2016, http://asbarez.com/138159/armenia-maintains-Tier-1-status-in-the-2015-trafficking-in-persons-report/.↩

09YEREVAN135↩

Author’s Interview with John Ordway, Ambassador to Armenia from November 2001 to August 2004, Friday March 6, 2015. Phone.↩

AZG DAILY #57, 26-03-2003, SERVANTS OF BLACK BUSINESS, http://www.azg.am/EN/2003032604↩

AZG DAILY #211, 19-11-2002: FIGHTING HUMAN TRAFFICKING, http://www.azg.am/EN/2002111901↩

Armenian official upbeat on fight against human trafficking.” BBC Summary of World Broadcasts. (June 18, 2004, Friday ): 662 words. LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date Accessed: 2012/02/21↩

Anti-trafficking Efforts in Armenia, Aghavni Eghiazaryan, 18:01, December 12, 2005. Published online. Last accessed on May 2, 2012 at http://hetq.am/eng/articles/9526/anti-trafficking-efforts-in-armenia.html↩

06YEREVAN761↩

04YEREVAN1344↩

See for example 06YEREVAN761↩

06YEREVAN960↩

07YEREVAN106, 07YEREVAN1437↩

06YEREVAN761↩

09YEREVAN494↩

08YEREVAN244↩

AZG DAILY #42, 04-03-2003, BRITISH EMBASSY LAUNCHES PROJECT TO RAISE AWARENESS ABOUT PEOPLE TRAFFICKING AND SMUGGLING, http://www.azg.am/EN/2003030402, http://www.armeniaforeignministry.com/fr/hr/hr_trafficking.html↩

04YEREVAN1344↩

06YEREVAN214↩

06YEREVAN1548↩

07YEREVAN1437, 08YEREVAN555, 09YEREVAN135↩

09YEREVAN135↩

06YEREVAN1548, 06YEREVAN1667, 09YEREVAN135↩

06YEREVAN214↩

05YEREVAN1387, 06YEREVAN895, 07YEREVAN250↩

04YEREVAN314↩

09YEREVAN865↩

07YEREVAN888↩

08YEREVAN555, 09YEREVAN135↩

07YEREVAN691↩

07YEREVAN106↩

09YEREVAN865↩