Argentina

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/argentina/.

PDFContents

The Argentine case demonstrates how controversial TIP legislation can be and that getting is passed is by no means an easy accomplishment. It also demonstrates the frustration and anger that can come from government officials when, despite their efforts and manifested progress, the US retains a low Tier rating. Even the US embassy, which had built up strong personal relationships with officials, became frustrated with the continued TIP Report criticism and recommended that the TIP office embrace a more conciliatory approach. On the positive side, the case demonstrates the painstaking involvement of the US in Argentina’s politics on trafficking, its role in bringing domestic officials to revise the legal definition of trafficking, its hand in facilitating inter- agency coordination and work with NGOs, its ability to influence domestic institutional design, and its funding of IGOs such as the IOM to carry out practical assistance programs, and the influence it can have when persistent and committed.

From the perspective of understanding the influence of scorecard diplomacy, the interactions show that Argentinian officials cared about Argentina’s rating, compared Argentina with other countries with similar rankings, and undertook actions with the aim of improving the rankings and the language in the report. It also illustrates how elites may respond with concern for their own careers or reputations and that this can be an important factor. Finally, the case illustrates the interaction with domestic forces. In terms of outcomes, the case reveals influence on laws, norms, practices and institutions. Clearly, some changes were facilitated by a strong impetus from within, especially driven in the later part of the case by a trafficking case that captured attention in the national media.

Background

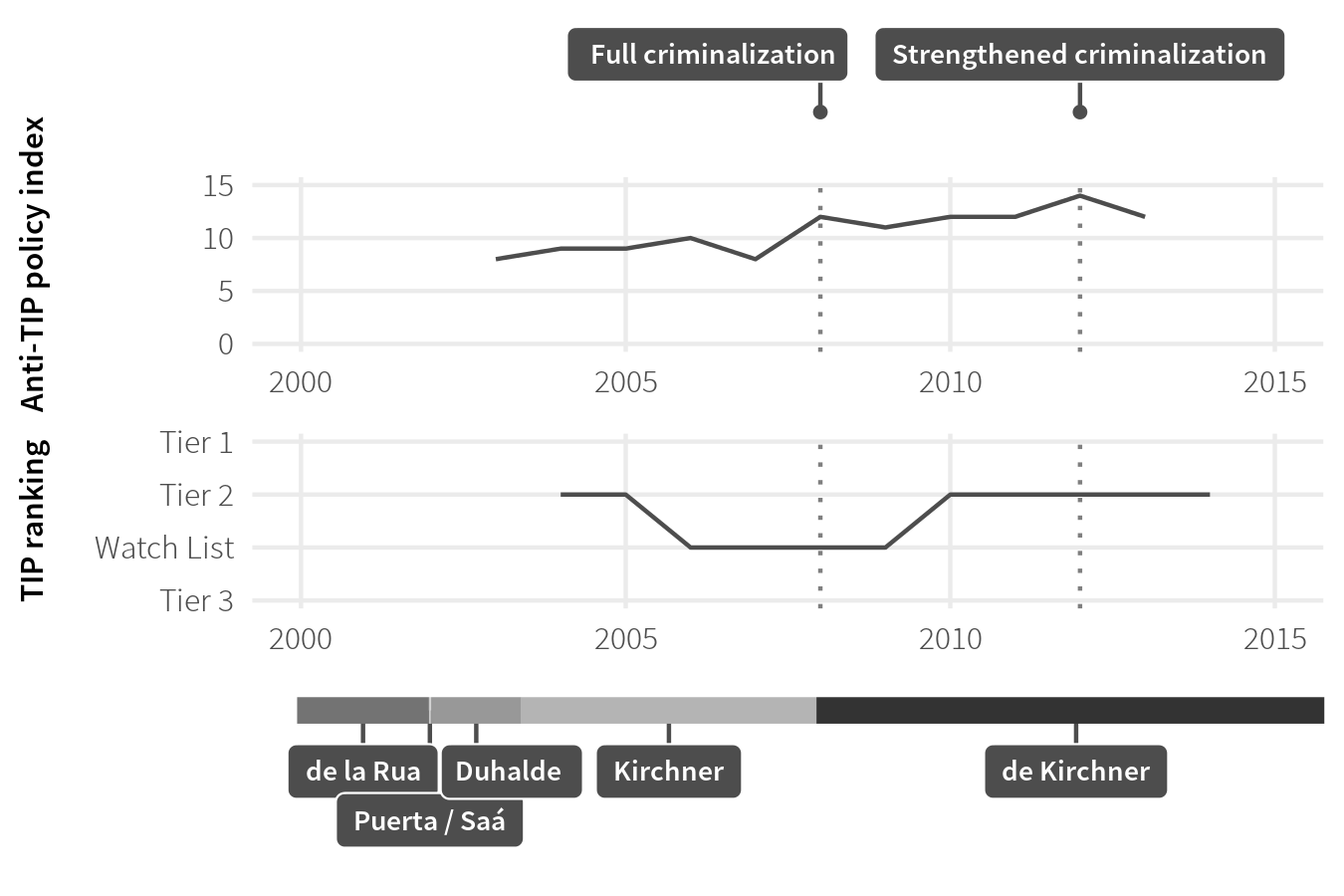

Argentina is a source, transit, and destination country for men, women, and children subjected to sex trafficking and forced labor. As a country with a history of serious human rights abuses that it adamantly wishes never to repeat, Argentina places a high priority on combatting trafficking, but nonetheless battles with widespread corruption and police complicity in the commercial sex industry. The 2015 TIP Report notes that according to the government, police are complicit in 40 percent of sex trafficking cases either as purchasers of commercial sex or as personal contacts of brothel owners. The different attitudes towards prostitution as sex-work or exploitation has contributed to debates around the role of consent and its relationship with human trafficking. Trafficking-related corruption is a serious concern among provincial officials.1 Several measures have addressed the trafficking problem over time, as reflected in the TIP policy index also shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Argentina’s TIP ranking and policy during governments, 2003–2014

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Average GDP per capita | $9,203.77 |

| Total aid | $108,138 million |

| Aid from US | $275.43 million |

| Average total aid as percent of GDP | 2.7% |

| Total TIP grants | $1,310,156 |

Table 1: Key Argentinian statistics, averaged 2001–2013

Direct diplomacy

The Argentinian embassy has been very active on TIP, mentioning it through numerous meetings with top-level officials. These included, President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner and other officials and policy makers such as the chief of cabinet minister, the justice and security minister, the interior minister, the foreign minister, the president of the senate, the speaker of the House, the Vice President of the House and many others. The documentation through the cables available begins in 2004 and the cables that discuss TIP constitute 9 percent of the overall available cables, suggesting that TIP was a highly discussed topic in general. Early efforts focused on influencing the passage and content of the 2008 law and pushed for the elimination of the notion of consent of victims. As Figure 1 shows, after Argentina entered the report in 2004, it has largely stayed on Tier 2, with the exception of a spell on the Watch List in the mid 2000s, which was intended to push for the passage of an anti-TIP law. US scorecard diplomacy also pressured Argentina to address official complicity in trafficking, provided technical assistance, and cooperated with IOM to train judges and officials. In addition, the US lobbied the government to formalize its inter-agency TIP coordination process and appoint a focal point to direct TIP-related activities, and encouraged the creation of the Trafficking Prevention and Assistance program. Throughout the years, the embassy worked hard to build relationships with local interlocutors, although the relations were sometimes strained. The embassy also provided draft legislation and practical assistance. Embassy officials tenaciously reinforced their points repeatedly with domestic officials.

Indirect pressure

Indirect pressure by third parties played an important role in Argentina. The media augmented the US scorecard diplomacy. For example, when the 2006 TIP Report came out in June 2006, the leading Clarín editorialized about the report’s placement of Argentina on the Watch List and argued that, “In view of this, the Government should promote the enactment of the draft bill against TIP, which is now in Congress… as well as take the struggle against the TIP seriously.”2 After the release of the 2007 report, the media heightened the comparative elements by noting that the watch list placement grouped Argentina with Mexico, Egypt, China, Libya, Russia, Cambodia, Armenia and Mozambique, among others, and pushed the report’s main recommendation by stressing that the “central point of criticism of Argentina is the delay of its Congress in passing legislation to fight trafficking in persons.”3

NGO activism also strengthened scorecard diplomacy. The embassy supported local NGO activist Susana Trimarco, who gained prominence by starting her own foundation after her daughter was trafficked. Local NGOs recognized her receipt of the US “International Woman of Courage” award as a key moment that increased attention to the issue, and they used the TIP Report to pressure the government.4 The relationship was mutual: Trimarco provided the US with information, while the award boosted her recognition and willingness of officials to meet with her.5 For example, on May 4, 2007, the ambassador met with Trimarco, and they agreed that the latest iteration of the draft anti-TIP bill was flawed and discussed activism strategies. 6 The ambassador then met with Interior Minister Aníbal Fernández and encouraged him to meet with Trimarco, which he did on May 15, after which Trimarco followed up with the embassy. The US thus facilitated government access.7 NGOs reported quite good relationships with the US.8 To the frustration of some politicians, NGOs used the TIP Reports to persist in making demands. One Argentinian researcher notes that “the [TIP] reports were an input frequently used by civil society organizations” to support their demands. 9 “NGOs took the TIP Report as a tool to pressure the government, that is clear to me,” she explained in an interview.10

IGOs were also active and interacted with the US. The IOM and the OAS both played their roles, with the IOM in particular at the forefront. That said, the US funded IGOs as part of its strategy. For example, the US paid the IOM to train judges and implement programs, including handling of individual cases and regional coordination workshops.11 The US also brought together NGOs, the IOM and the government.12

Concerns

The interactions demonstrate that Argentinian officials cared about Argentina’s rating, compared Argentina with other countries with similar rankings, and acted to improve the rankings and the language in the report. Individual officials who became vested in the cause, especially Fernández, who at times took the issue very personally, drove progress. These officials explicitly asked whether the 2008 passage of the law would “change [US] coverage of the issue in future reports”13 and said they hoped this effort would be boost the next Tier rating.14 They also considered about Argentina’s standing in the international community. For example, Foreign Minister Jorge Taiana asked the ambassador rhetorically, “how can anyone think that the TIP problem is worse in Argentina than in surrounding countries?”15

The case illustrates how elites may respond with concern for their own careers or reputations. An anonymous source familiar with the career officials said they responded to the criticisms and wanted attention for their accomplishments and that this motivated them to align their efforts with the US priorities. The source recalled that once Marcelo Colombo, Head of the Prosecutor’s Office for the Combatting of Trafficking and Exploitation of Persons, was upset about getting a “bad grade” on the TIP Report, “saying it was bullshit, but he still does what the report says. For example now the TIP Report is saying that they should prosecute public officials for complicity… []… and now he’s very interested in that.” The source explained that many bureaucracies in the government try to enlarge their influence and get attention to what they are doing, and getting attention from the US is a way to get attention for their work and gain power.”16

Outcomes

Legislation

The US used scorecard diplomacy to engage Argentina heavily on the content of legislation. Although Argentina helped create the UN Trafficking Protocol,17 the government struggled to bring its own domestic legislation into compliance with the protocol. When Argentina first entered the TIP Report in 2004, domestic anti-trafficking legislation was still missing. In June 2006, the TIP Report demoted Argentina to the watch list. Subsequently, the US engagement on the TIP issue peaked in April and May 2007 with numerous ministerial level meetings each month.

Once drafting of the legislation began, the US TIP Report and the embassy pushed hard for the text to omit a clause favored by local politicians, who benefitted from it though corrupt dealings with local brothels. The clause required adult victims to prove that they did not consent to their condition, something many feminist abolitionist women’s groups and NGOs agreed with the US would make it even harder to prosecute traffickers, while sex worker activists disagreed on the basis that excluding consent from the law would conflate consensual sex work with trafficking. The US embassy repeatedly suggested in personal meetings that the consent clause should be removed from the bill, and the fact that the TIP Report kept Argentina on the Watch List in 2007 kept up the pressure for the bill’s passage. This caused some conflict with the embassy’s main interlocutor, Interior Minister Aníbal Fernández. In a personal interview, he expressed that while overall he had a good relationship with the US on this issue, when a US official attempted to give him a “corrected” version of Argentina’s anti-TIP bill draft during a 2007 to DC, he felt the US was overstepping its role.18 He understood the US position on consent but also blamed it for delaying the law’s passage.19 Regardless of the negative signals from Fernandez, the ambassador continued to push for the bill and the specific language, meeting with ministers throughout the fall and delivering speeches urging the passage of TIP legislation.20 After the election, a spate of meetings ensued between US officials and Argentinians, including the newly elected president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and the new interior minister, legislators, and the National Ombudsman. 21 Because of the domestic power struggles, even the president eventually supported the inclusion of the consent clause as a necessary compromise, and so when the law passed in 2008 it retained this provision.

While former Minister Fernández downplayed US involvement, instead taking more personal credit, non-governmental actors gave the US some credit for the passage of the 2008 law, which led to more shelters and improved justice.22 Nonetheless, though the US embassy and many domestic groups recognized the law as progress, they continued to emphasize the need for the consent clause to be modified. In December 2012, Argentina finally changed the law on the issue of consent, a move attributable partly to the influence of the US,23 although, by 2012, NGOs were really in the forefront of pushing for the change to the law. The final trigger was a big court case that acquitted the accused traffickers of Marita Verón, whose case had dominated national news due to efforts by her mother, Susana Trimarco.24 Still, multiple interviewees recognized that the US’ financial support of Trimarco’s organization and their awarding her with the International Woman of Courage Award in 2007 were key in getting her daughter’s case on the public agenda.25 The US thus played a significant role in the passage and content of the legislation in Argentina, and the embassy did so by using the Tier ratings to employ pressure and engage extensively in one-on-one high-level diplomacy, as well as by working though NGOs.

Institution building

The case of Argentina shows how scorecard diplomacy can stimulate the creation of domestic institutions to deal with TIP. Because multiple stakeholders were concerned about the Tier ratings, the embassy was able to engage them on implementation issues, which sometimes influenced institutional choices. The focus was not only on the passage of the law, but also on its implementation and on proper treatment of victims, for which the US provided both funding and training. The US TIP related advice sometimes intruded into Argentina domestic governance. For example, in 2004 when the government struggled with inter- agency coordination, the US lobbied the government to formalize its inter- agency TIP coordination process and appoint a focal point to direct TIP-related activities by year’s end. Subsequently, the government identified such a focal point in the Federal Office of Victim’s Assistance under the Attorney General’s Office.26 Likewise, in 2007 the US was pushing in the report for better assistance for victims. Later in 2007 the government created the Trafficking Prevention and Assistance program in the department of Justice, the program that had been mentioned in the recent TIP Report.

In 2012, the TIP hero award also bestowed more authority on Marcelo Colombo, Head of the Prosecutor’s Office for the Combatting of Trafficking and Exploitation of Persons, who said in a personal interview that the recognition of the award had made his work better known outside Argentina and facilitated cooperation with the UNODC.27

The promotion and adoption of new norms and practices

As part of the scorecard diplomacy effort, the US embassy participated actively in the discussion of the concept of trafficking. It was not alone in promoting its perspective, but it added a powerful voice. The US’ influence was evident around the debate about consent. In Argentina victims were seen as complicit if they initially consented, which placed the burden on them to prove that they had not consented. Although the government held onto this view for years, some Argentinian politicians and civil society actors understood the problems with this framing of consent. For example, Argentina’s National Public Defender said at a human trafficking conference that a victim could not consent to his or her own exploitation and urged the passage of the comprehensive TIP bill.28 Still, the issue of consent required considerable educational effort and the US worked with the government, provincial governments, and civil society to raise awareness about the problem of the notion of victim’s consent.29 Judges in Argentina also did not understand the need to treat TIP victims carefully. NGOs reported that victims were sometimes asked if they initially consented to the activities and if they answered yes this was used as proof that they were not trafficked. After the new TIP law was passed, officials from the ministry of justice noted that some federal judges did not grant extensions to law enforcement authorities to give them more time to obtain testimony from potential trafficking victims and that many judges and prosecutors had yet to fully understand the issues or their importance. The US funded its own experts to lead training workshops for judges and others, and also funded similar IOM trainings, thus facilitating learning and socialization around the concepts of consent and proper treatment of victims.30 The US also pointed to best practices on the issue, not only in the report, but also directly: During a visit, two U.S. Representatives showed the interior minister how Colombia had recently changed its TIP legislation to remove the issue of consent as a consideration for adults.31 After the narrower version of the law passed, the embassy continued to work to educate the federal and provincial governments on victim’s consent32 Meanwhile, some judges understood the problem. For example, after the law was passed, a federal court ruled that that no one could consent to his or her own exploitation.33 Thus, the US was able to use scorecard diplomacy to work with local actors, both government officials and NGOs, to stress the issue of consent.

Conditioning factors

Scorecard diplomacy faced some major obstacles in Argentina because of the widespread official complicity in trafficking, especially at the local level. In addition, the government was unstable at times. Prior to 2007, strained US- Argentinian relations also blocked constructive cooperation on TIP. The US had some strong interlocutors and access to high-level officials, although sometimes the embassy was also met with resistance from government officials and resistance to US interference in domestic politics. That said, the active NGO community was a major asset to the US efforts and one the embassy actively cultivated. It was important that the US was willing to assert pressure, as demonstrated by the tenaciousness of embassy officials in reinforcing their points repeatedly with domestic officials.

07BUENOSAIRES1723, 07BUENOSAIRES1353↩

06BUENOSAIRES1340↩

07BUENOSAIRES1162↩

Personal interview with Luján Araujo, Fundación María de los Ángeles, October 22, 2015. Conducted via email by Jessica Van Meir. Translated from Spanish by Jessica Van Meir.

Personal interview with Viviana Caminos, Red Alto a la Trata y el Tráfico, August 29, 2015. Conducted in person by Jessica Van Meir. Translated from Spanish by Jessica Van Meir.

Personal interview with Marcela Rodriguez, Program of Advice and Sponsorship for Victims of Trafficking in Persons, December 2, 2015. Conducted via video chat by Jessica Van Meir.

Personal interview with Cecilia Varela, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET). July 8, 2015. Buenos Aires. Conducted in person by Jessica Van Meir.↩

For example: Susana Trimarco met with the ambassador May 4, 2007 and updated him on the bill and discussed its shortcomings with him (07BUENOSAIRES965).” Trimarco kept the ambassador abreast of her meetings with various politicians about the legislation and the ambassador also mentioned Trimarco to politicians and urged them to meet with her (07BUENOSAIRES965 (07BUENOSAIRES965)).”↩

07BUENOSAIRES965↩

07BUENOSAIRES965↩

Personal interview with Carla Majdalani, Asociación Civil La Casa del Encuentro. June 25, 2015. Conducted via video chat by Jessica Van Meir.↩

Varela 2012, 49↩

Personal interview with Cecilia Varela, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET). July 8, 2015. Buenos Aires. Conducted in person by Jessica Van Meir.↩

06BUENOSAIRES309↩

05BUENOSAIRES190, 07BUENOSAIRES1113↩

08BUENOSAIRES589↩

08BUENOSAIRES520↩

07BUENOSAIRES1302↩

Anonymous interview. Conducted in person by Jessica Van Meir.↩

Gallagher 2001, 982↩

Personal interview with Aníbal Fernandez, Chief of the Argentine Cabinet of Ministers, November 24, 2015. Conducted via video chat by Jessica Van Meir. Translated from Spanish by Jessica Van Meir.↩

08BUENOSAIRES425↩

07BUENOSAIRES1888, 07BUENOSAIRES2119, 07BUENOSAIRES2095, 07BUENOSAIRES2290↩

08BUENOSAIRES172, 08BUENOSAIRES390, 08BUENOSAIRES438↩

Personal interview with Monique Altschul, Asociación Civil La Casa del Encuentro. July 10, 2015. Buenos Aires. In person interview by Jessica Van Meir.↩

Varela Interview↩

Araujo Interview, Caminos interview, Colombo interview, Encinas interview, and Rodriguez interview.↩

Araujo interview, Caminos interview, Rodriguez interview, Varela interview.↩

05BUENOSAIRES190↩

Colombo interview.↩

07BUENOSAIRES2244↩

08BUENOSAIRES172↩

06BUENOSAIRES309↩

07BUENOSAIRES2300↩

08BUENOSAIRES172↩

09BUENOSAIRES1103↩