Case studies

How to cite: Judith G. Kelley. “Case Study Supplement: A Closer Look at Outcomes. A Companion to Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior, published by Cambridge University Press, 2017.” Published online April 2017 at https://www.scorecarddiplomacy.org/case-studies/.

PDFContents

While many more cases are touched upon in the book manuscript, in all 15 cases were studied in depth. These included: Argentina, Armenia, Chad, Ecuador, Honduras, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, and Zimbabwe. The case studies form the base of this book. Only Armenia, Israel, Japan, and Zimbabwe were selected for fuller discussion in the book itself. All the case studies are therefore discussed here more fully. This cases here should be read in conjunction with the book. In particular, the case study selection as well as data comparing cases with non-cases is discussed in the Methods Appendix of the book and should be read before reading these cases.

These case studies provide the background for the coding in Tables A6.6–9 in the book. They also provide the background for the discussion in Chapters 7 and 8 in particular.

Defining outcomes: The human trafficking situation or government efforts?

It is important to be clear about how to think about outcomes for research on scorecard diplomacy. In the case of human trafficking, one might argue that one should ultimately consider whether the larger problem of human trafficking has been mitigated in meaningful ways on the ground. This is very difficult, however, because data on actual human trafficking outcomes is very poor. Indeed, our increasing access to better data also obscures trends in outcomes, although data on prosecutions and convictions, presented in the book, give some base lines at least for increased successes in fighting human trafficking.

Regardless of which data or measures one uses, in most countries the results of scorecard diplomacy on human trafficking outcomes has been mixed. The problem clearly persists even in countries that fight it hard; no country can declare victory. Human trafficking is a horrific and obstinate crime. Like murders, government efforts can mitigate their frequency, but the problem is unlikely to be eradicated in the absence of the eradication of very deep-seated and complex societal causes.1 Countries’ efforts to fight trafficking cannot be measured at any given time as being accomplished or not. The nature of human trafficking is such that there is no final outcome per se, only ongoing efforts to fight it, and these efforts may ebb and wane. Indeed, this is one of the motivations of the US TIP Report’s ongoing nature. Government efforts are supposed to be sustained to maintain good rankings, and this endeavor never anticipates completion. Government attention to the problem has also proven sporadic in many countries. Even the US could do far more to fight trafficking within its borders, but the issue must compete for resources and attention like any other issue.

Instead of focusing on measures of the human trafficking outcomes data, another way is to consider the effectiveness of scorecard diplomacy is to consider the efforts countries are making to address trafficking and in this case more specifically their responses to US efforts to push certain recommendations for how to do so. This is more aligned with the more immediate objectives of scorecard diplomacy as it assesses the extent to which the policy is effective as motivating desired changes, rather than whether those policy solutions are actually the optimal ones. Therefore, the outcomes in these cases focus on diplomatic “successes.” The cases describe incidents in countries that constituted some progress at that point in time according to the policies the US was pushing. In the cases it is possible to observe some incidents or periods when the US efforts appear to have considerable traction and help move things forward, while at other times there is stagnation or backsliding. Progress may occur when a policy advances, a new agency is created, a shelter is built or a new action plan is drawn up. Again, that does not mean that the country has solved the problem, or that the efforts have been maintained at high standards. It simple illustrates instances where some progress was made, or, conversely, times when it failed.

The case study methodology as well as the case selection is discussed in the Methodological Appendix of the book. As explained there, in drawing inferences about US influence, the analysis paid attention not only to sequencing, but also to the congruence between the substance of US recommendation and country behavior as well as statements by people involved that directly addressed causality.

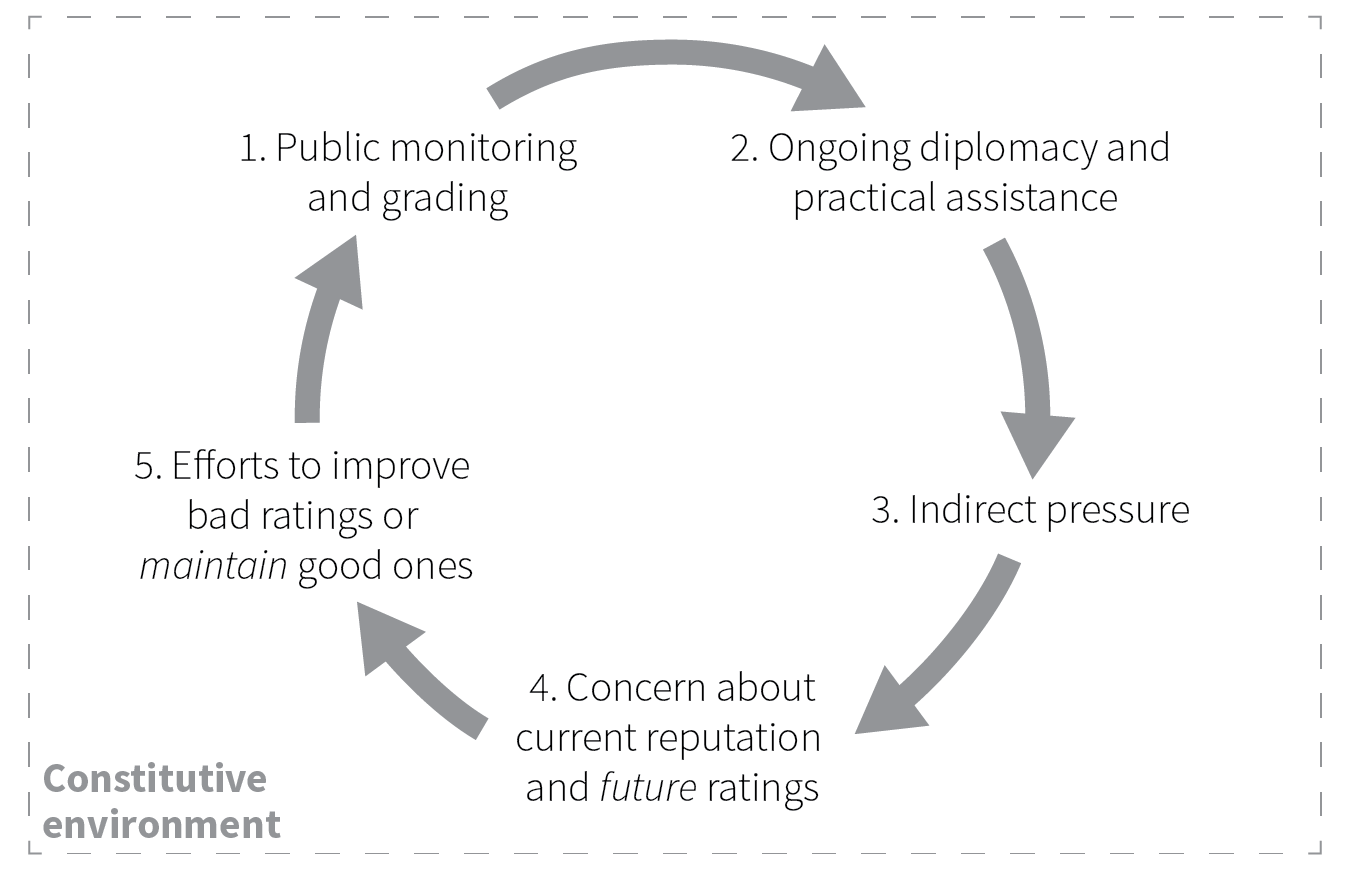

Because the case studies aim to understand scorecard diplomacy, they have been reorganized from chronological accounts into discussions of the major steps of the scorecard diplomacy cycle, shown in Figure A.

Figure A: The scorecard diplomacy cycle

Each case begins with a summary of the scorecard diplomacy of the case, followed by a very brief account of the trafficking situation in each country. This account is based mostly on recent TIP Reports, which interested readers should read for much greater details. The case studies then discuss the indirect pressure by NGOs, IGOs and the media and analyze the nature of the concerns revealed in the cases. The next sections discuss the results in terms of traceable effects of scorecard diplomacy on legislation, institutions, norms and practices. Each case study ends by discussing any factors that conditioned the influence of scorecard diplomacy.

References

Wheaton, Elizabeth M, Edward J Schauer, and Thomas V Galli. 2010. Economics of human trafficking. International Migration 48 (4): 114-141.

Wheaton, Schauer, and Galli 2010.↩